While anxiety about attending events remains high amongst disabled people, Anne Torregiani says the Covid online content boom has seen revolutionary opportunities that could improve access for good.

Stefano Intintoli

As organisations re-open with the emphasis on ‘building back better’, one silver lining of the Covid cloud is a marked commitment to being more audience-centred, listening and adapting to audience needs in very live and thoughtful ways. This trend could and should be a win for disabled audiences and in turn, of course, a win for the sector.

At The Audience Agency, our research shows that, while disabled audiences are far less likely to feel confident about returning to in-person events, what limited some audiences through the pandemic may have liberated others.

Pre-covid analysis from Audience Finder showed that disabled people were consistently under-represented among in-person audiences and that those who did engage did so less frequently. Now that organisations have developed the habit of sounding out audience’s views on access and user-experience, is there an opportunity for that to change?

We can also see that the digital content boom triggered by Covid is making a big difference to disabled people. We have long been aware of a small but significant group of disabled ‘super users’ of online cultural offerings and, importantly, this group seems to be increasing in size and frequency. What do we need to do to nurture this growth? How might we capitalise on these lessons and accelerate the momentum to engage disabled audiences more meaningfully in the ‘new normal’?

Realistic about COVID inequality

We have to start by recognising that things are even less equal than before. Overall, disabled people have been disproportionately disadvantaged by the pandemic, economically and in terms of health, anxiety, and cultural participation. Despite excitement that our online culture offers have dismantled barriers to disabled people’s arts participation, they still only benefit a minority.

The Cultural Participation Monitor tells us that disabled people are more worried about getting Covid and less likely to be happy to begin re-attending live cultural events. So, we can expect that the proportion of in-person disabled audiences will be even smaller post-Covid, unless substantial changes are made.

We know that disabled audiences were underrepresented, and Covid has made that worse, with both disabled audiences and creatives facing additional barriers to access since the start of the pandemic, and continuing uncertainty about how and if they can safely return to work and leisure.

In other words, Covid has had an excluding effect even if recent experience has shown us how we MIGHT do things in a more inclusive and accessible way. There is a need. We know more about answering that need. But we will need major commitment and investment to change well established trends.

Listen and adapt

Turning to the experience of arts-interested disabled people should give us ideas and inspiration. Ratings are broadly similar for disabled and non-disabled audiences, in terms of both the quality of the cultural product itself (76% vs 74% ‘very good’), value for money (57% vs 56% ‘very good’) and the overall experience (both 72% ‘very good’).

Disabled audiences are older on average, less well-off and less highly-educated. Nevertheless, they lean towards slightly different main motivations, with 15% saying that arts and culture experiences are ‘an important part of who I am’, compared to 10% overall. We associate this motivation with being an enthusiast, which reinforces the idea that disabled audiences tend on average to be more committed and culture confident. Another way of looking at it is that they need to be more motivated to navigate the barriers to access we create.

In short, if we want to build bigger disabled audiences, we will have to apply new-found listening and adapting skills to the needs of disabled people who may be interested in our offers but put off by some aspects of the experience. Disabled people say that key factors include flexibility, price and pre-planning information.

The time is now

In July, Arts Council England noted that “caution is evident among those across society who have been impacted most by the pandemic, including disabled people and the clinically extremely vulnerable”, and urged organisations to prioritise accessibility and inclusivity. Our colleagues in Centre for Cultural Value’s Covid Impact research have demonstrated that more disabled people have lost jobs in the creative industries UK than non-disabled workers.

The UK Disability Arts Alliance 2021 Survey Report noted that more than half of disabled culture professionals had less or no work since the pandemic began, and more than two thirds remained worried about their future in the industry. As with ACE’s statement, the DAA emphasises that there is a small window in which to act to ensure disabled artists and audiences remain able to engage with the sector.

Right now, we need to make sure that the interests of disabled people are at the forefront of our thinking as we redesign audience experiences. Getting the experience right for disabled people will have universal benefit. As urgently, we need to address the precarity of disabled artists – their leadership in the cultural sector is critical to long term inclusion.

The future of access is (also) digital

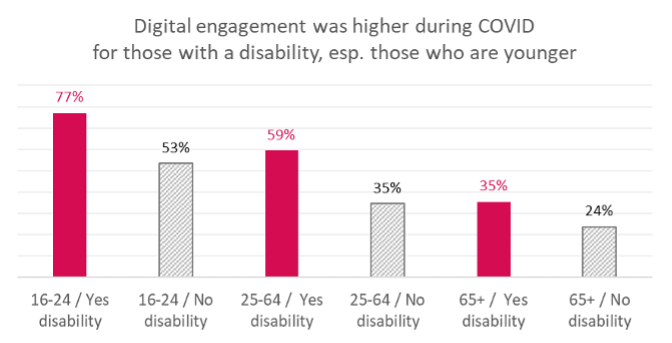

Digital engagement has been particularly important for some disabled people. Even before Covid, 47% had engaged with a range of cultural activities, compared to 38% on non-disabled people. But during Covid, the difference in digital engagement really opened up, with 57% compared to 35%.

Overall, our Cultural Participation Monitor shows that offering online access during Covid has made far more of a difference for disabled audiences than others, a finding supported by both our 2021 Digital Audience Survey and, crucially, audience’s own testimonials:

“I am a permanent wheelchair user with quite specific requirements and also an avid theatre goer. Quite frankly the burst of productions suddenly available to stream at the beginning of the pandemic was joyful. I had choices that I'd never had before, I could look at things and, if I liked the look of it, I didn't have to investigate how I might get there, or whether when I did get there they would be able to accommodate me. I didn’t have to worry about whether I would have to have a companion, and if that companion would have to lift me into an out of places. It was also really fabulous, not having to think: Is public transport available? Will people be wearing masks? Will it be too busy? Will a lift be broken? It's been an actually fantastic experience, this surge in availability of online theatrical arts, and I don't want it to end with the pandemic.” - Ria Milton, theatre goer.

These words sum up how intertwined our digital and access strategies need to be in future.

The Cultural Participation Monitor also shows very clearly that younger people are the most avid consumers of online engagement, unlike in-person, and that age difference is even more marked among disabled people.

The fact that such a large proportion of young disabled people are engaging with a broad range of online culture seems a major opportunity. Although this does not include Netflix and the like, we need to acknowledge that the content sources that younger consumers are seeking are many and varied. We need to know more about what, how and why.

It’s tempting, amongst the excitement across the arts sector for reopening in-person, to decelerate the progress made in digital culture. All our research underlines the fact that being genuinely accessible in the future – and for future generations - will demand a strong online content strategy and the openness to engage with users, especially, younger consumers and participants – disabled and otherwise - about their interests and habits.

Better together

So while there’s much to be done, there are clear opportunities for change. There’s no doubt that long-term, full-on commitment to increasing access is much easier to say than do and that long-term, full-on dedicated funding would help greatly. But we can also work together across the sector and with our disabled stakeholders to make positive change.

Here are 5 things you can do:

- As you design your digital content strategy and approach, remember that disabled users are major stakeholders.

- Talk with your disabled users – online and in-person - and make sure you consider their emerging access needs specifically in any consultation or feedback.

- Make sure you identify disabled people and their specific preferences in any research you do – the free Audience Finder survey can help you do this.

- Think about setting up an advisory panel of disabled users – audiences and/or artists: you could collaborate with some other like/near organisations to do this.

- You could also approach local disability networks for advice, especially if you have something to offer back.

- Keep an eye on the research – Sector Support Organisations like us, Vocal-eyes, Stagetext, Attitude is Everything, and so many others – are doing a lot to keep abreast of issues for disabled audiences as they change – look out for fresh reports.

- Keep supporting disabled artists.

Anne Torreggiani is CEO of The Audience Agency and co-director of the Centre for Cultural Value.

![]() @audienceagents | @TorreggianiAnne | @valuingculture

@audienceagents | @TorreggianiAnne | @valuingculture

This article, sponsored and contributed by The Audience Agency, is part of a series sharing insights into the audiences for arts and culture.

- Log in to post comments