Meurig Bowen sees no problem with the current proliferation of festivals in the UK.

Festivals, like universities, out-of-town shopping centres and cosmetic surgeons, have expereinced a population explosion in recent years. Some of them are free, while others are fantastically expensive and exclusive. Some derive their success and reputation from encompassing many artforms, while the identity of others is achieved primarily by their narrow focus, whether it be puppetry, comedy or real ale.

There is something wonderfully wild-west, indefatigable and regulation-free about the UK festival scene

The music critic Michael White describes the proliferation of festivals in this month’s edition of Opera Now magazine as a ‘festive epidemic’, and quotes a ‘guestimate’ from BAFA following a 2007 survey that there are 20,000 in the UK alone.

That is, indeed, an awful lot of festivals. And as Holly Payton-Lombardo pointed out in last week’s BAFA debate article, the word ‘festival’ is ever more prone to having liberties taken with it. So much so, that one of the ensuing strands of debate on Twitter last week reflected on how it might be reclaimed or even renamed: fostivals, fustivals, fistivials were all suggested. But actually the best re-name is already taken: the foodie-family-music gathering in Oxfordshire, Feastival. For it is no coincidence that Feast and Fest come from the same Latin root for a food-filled religious holiday.

If it is not quantity that fails to impress a certain kind of spiky-viewed metropolitan arts writer, it is the quality. “Most lack any compelling raison d’etre, vision, adventure or distinguishing marks,” wrote the brilliantly provocative journalist Richard Morrison in the BBC Music Magazine a few years ago. But not all festivals can set as their primary aim the creation of unique, important, high-end work that might set the arts elite a-chattering. For many festivals, being of the community, and being for the community is what it is much more about.

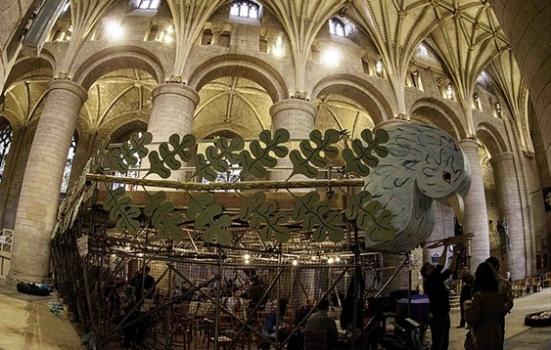

Whatever their vision, whatever their perceived intrinsic quality, the principle outcome of a widened festival-scape has been the decentralisation of the UK’s arts scene. If only for a few days or a couple of weeks at a time, lights shine elsewhere on this island’s map than on the grand and self-important metropolises. Remarkable things happen in sometimes unremarkable places. Or, just as often, such remarkable things happen in equally remarkable, otherwise rarely visited places. Out of the way churches, castles and derelict factories become the nation’s temporary concert halls, theatres and exhibition spaces. Imagination can run riot, communities can surprise themselves and civic pride can be twitched by the enlivening impetus of something special on our doorstep.

It is not just the specialness of that single festival event; it is the collision and connection of several adjacent events that mark out a unique territory for festivals. If a season-long concert series or theatre subscription are well-spaced meals, the immersion of a festival represents a feasting banquet. There may be abundant thematic cohesion, or none at all, in the unique path a festival-goer sets out on, but the diversity of ideas and experiences available can be intoxicating and thrilling in the way that a slower-burn series or season probably cannot be.

Holly Payton-Lombardo’s article stated that festivals “record the patterns of cultural change”. There is probably a doctorate or a book to be generated from that compact assertion. And such a tome might investigate the rise and rise of literature festivals, the rapid emergence of science festivals and science programming within arts festivals, the camping festival’s yin and yang of mega and boutique and the complex journey of classical music since the pioneering postwar years (programmed more marginally by some of the ‘majors’ and much multiplied elsewhere in trimmer, diverse and more sustainable formats).

A hard-headed management consultant type, if airlifted in to look at the UK arts festivals scene, might easily draw the conclusion that some serious pruning is required. Less might be more. Fewer might be better. And the relatively small amount of ACE money dedicated to festivals, compared with that assigned to building-based or year-round clients, would go further (ditto funds like PRSF).

But there is something wonderfully wild-west, indefatigable and regulation-free about the UK festival scene − where for every outfit that might run out of artistic or financial steam, another three will pop up nearby within the year. It is survival of the fittest, the most imaginative and the most solidly determined all rolled into one. And if each one of those survivors puts things on where people turn up and succeeds in delighting, provoking, challenging or touching souls, then the potentially irksome “what’s the point of festivals” question will have been successfully parked for another day.

Meurig Bowen is Music Festival Director at Cheltenham Festivals.

www.bafanl.co.uk

www.cheltenhamfestivals.com

To keep this conversation going and to join the debate tell us what you think is the point of festivals. We are hosting a discussion on Twitter on Thursday 24 October from 5pm: #thepointoffestivals.

www.artsfestivals.co.uk

Tw: @BritArtsFests

www.worldfestivalnet.com

The annual Conference for Festivals, hosted by BAFA, is to be held in Edinburgh on Thursday 7 and Friday 8 November.