What makes a good client for a major capital building project? Alan Tovey makes some suggestions

The past year has witnessed the opening of a remarkable array of new arts building projects around the UK. But although venues such as the Hepworth Wakefield and Turner Contemporary brought ‘culture-led regeneration’ once more to many people’s lips, no-one believes that we’re reliving the heady early years of this century. In 2012, the money simply isn’t there: Arts Council England (ACE) has made it clear that we shouldn’t expect any more large-scale projects in the foreseeable future. It’s now commercial galleries, private foundations or individuals that are bringing new projects forward, such as the Jerwood Gallery in Hastings or Damien Hirst’s plans for a gallery to house his own collection.

The austere public funding climate, and sobering research by the University of Cambridge* about the problems that have beset some of the existing Lottery funded projects, have made us stop and think. The casualties are well-known: no-one wants to join the National Centre for Popular Music in Sheffield on the list of the fallen, or suffer the painful evolution of The Public in West Bromwich. What lessons can be given to those who remain or are planning new cultural buildings?

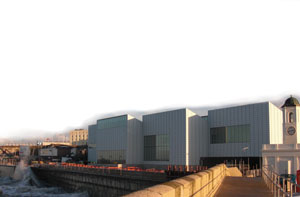

We have been privileged to work on many great recent projects. We have acted as project monitors for ACE on the Hepworth Wakefield and Turner Margate, and were brought in to get Rafael Vinoly’s firstsite in Colchester back on track and open following its earlier difficulties. We’re currently working as project monitors for the Heritage Lottery Fund at the Whitworth Gallery and with commercial private clients. Our experience tells us that things are different now, and that the degree of recklessness and inexperience that characterised many early Lottery-funded projects has thankfully gone. The economic climate has sharpened minds, and experience borne from the first wave of major Lottery-funded projects has been brought to bear. Funding bodies have also adapted and new funding rounds are subject to a more cautious and phased approach. All have been subject to much closer financial, political and media scrutiny.

What are the common pitfalls and problems for major projects and how can they be avoided? There are key issues that need to be recognised and addressed by the team from the outset. Many cultural clients find themselves dealing with complex funding arrangements, very large budgets and high expectations, yet have little experience of major capital projects. Being the client isn’t a part-time job – it takes time and needs to be planned for. Engaging a project champion to provide client-side direction, organisation and drive can help clients to focus and establish productive lines of communication with their funders and stakeholders. Success depends on good organisation and clear decision-making, and it’s important to have a suitably qualified client-side project manager whose leadership is recognised across the organisation. A good project manager will establish a clear structure to enable the client and other stakeholders to deal with day-to-day issues and focus with the design team on delivering a first class project.

Good clients understand the need to take, and follow, good advice. Selecting the right team of advisors with the right experience (and at the right price) is crucial. The Cambridge University report made for sad reading in places: one experienced arts professional was quoted as saying she would “never, never, never do a building again, because it is just too stressful”. Another said that “arts buildings are seriously bad for your artistic health”. It doesn’t have to be so. With a good team in place and good advice close to hand, it’s possible to create an outstanding building that fulfils its brief and keeps you sane. That’s what professional advice is for.

Budgets must be realistic in supporting the client’s aspirations, reflecting the complexity of the development. A clear and rational brief needs to be provided and agreed at an early stage, and the team needs to stick to it and avoid assuming the budget will expand to accommodate a moving brief. All too often it won’t, simply because it can’t. We know that good design does not necessarily cost more money, and that a clear mutual understanding of the client’s vision and the architects’ intentions is key. Buildings like the Hepworth and Turner are exquisite pieces of design where the client and project team fully understood each other, and planned the project and the budget accordingly. If teams can get this right, then value-engineering can be avoided.

We all have a part to play in getting projects right, from agreeing the brief and sticking to it, assembling a funding package that can support that brief, getting team structure (internally and externally) right, and pushing the whole project team to embrace the project and deliver the very best service. It is good to see more arts buildings still coming forward with thoughtful, ambitious clients behind them. The audiences remain – in grim economic times perhaps more than ever. We shouldn’t be too hard on ourselves – there have been mistakes but I’m confident that lessons have been heeded.

Alan Tovey is a Partner at Jackson Coles. W www.jacksoncoles.co.uk Tw @jacksoncoles *C. Alan Short et al (2011) Geometry and Atmosphere, Ashgate