Cathy Hirschmann learnt more than she expected from a fellowship at one of the great US arts organisations, with its 600-stong board team, huge private funding and a charismatic president.

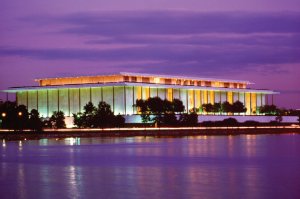

The John F Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington DC has a dual remit as a memorial to John F Kennedy and the country’s national cultural centre. It has a local, national and international focus on producing and presenting, nurturing emerging creative voices and delivering a diverse education programme. With nine stages (ranging from a concert hall, opera house and large- scale theatre to an intimate jazz club), as well as nationwide and international touring, the centre presents almost 2,000 performances each year, employs around 1,200 staff and has a turnover of around $150m. The Center’s President Michael M Kaiser has a personal commitment to arts management training – the seeds of the current fellowship programme grew while he was Executive Director at the Royal Opera House. Now in its eighth year, the fellowship offers ten international mid-career arts professionals the opportunity to study and work with Kaiser and the Vice-Presidents of Development and Marketing, attend a seminar series covering all aspects of arts management, experience practical placements in three departments and undertake cross-departmental and strategic projects. For the past nine months I have been an Arts Management Fellow at the Center.

Out of the comfort zone

My most recent posts were as Administrative Producer at Scottish theatre company Visible Fictions, and Programmes Manager at Arts & Business Scotland. When I began my fellowship in September 2008 I was immediately presented with experiences beyond the familiar. Navigating the rabbit warren of administrative offices which curl around the numerous performance, rehearsal and production spaces was like arriving in a new city without a map. This size also produced a different approach to communication. The person you need to speak to isn’t sitting across the room and the rules of a structured hierarchy mean you need to talk to several people en route. A very welcome element of the size is the sheer volume and variety of productions. Fellows are effectively given a free pass to see performances and this means the opportunity to see several each week and often more than one in an evening. I shared the experience with nine others: four Americans, and one each from Canada, China, the Czech Republic, Portugal and Egypt. The mix was diverse not only in nationality but also in experience, with the group including a human resources director, artistic director, production manager, marketing director and executive director. The opportunities to learn from each other were immense.

Show me the money

US arts organisations raise a comparably large proportion of their income from private sources. In 2007 the Kennedy Center generated $73.8m in earned revenue and fundraised $64.5m, of which over $51m was from private sources. In the same year the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts raised 66% of its income from private sources, the New World Symphony 80% and the Smith Center for the Performing Arts 88%. As we started learning about and working in the Center, the implications of the different funding structure were immediately striking. No outside agency approves their artistic programming or business plans and, while public benefit is important to the centre, in general there is not the same requirement to increase, document and report this. For example, there is not a persistent focus on developing new, younger and more diverse audiences or any formal structure to elicit audience feedback. These things do happen, but the drivers and reporting structures are very different. We also quickly saw how the use of boards is an essential part of the fundraising strategy to sustain the required levels of private support. The Kennedy Center has ten boards (effectively committees with no fiduciary responsibilities) plus the Board of Trustees. Together, they have a membership in excess of 600. Organised, supported and nurtured superbly, these individuals provide an immensely effective group of donors, advocates and fundraisers.

Open doors

One of the extraordinary elements of the fellowship was the absolute commitment and desire of the senior staff to let us deep into their practices, strategies and concerns. Behind the closed doors of a fellows’ class they presented us with many live case studies in their dedication to our learning and development. At a time of worldwide financial turmoil this was particularly revealing and informative. We observed the budgets being trimmed and income targets – on both the earned and contributed sides – being reviewed. Each week we reviewed actual ticket sales versus budgets with the Vice-President of Marketing and discussed tactical shifts to counter any weak areas over the coming months. Sales were less buoyant during the autumn – in a political city this was potentially the impact of the election as much as the economy – and, like many organisations, the Center was experiencing more selective audiences. However, innovative high-quality programming combined with appropriate marketing strategies was still attracting ticket buyers and donors. Although budgets were being pulled back, the President’s focus on investing in programming and marketing prevailed. One of the fundamentals of Kaiser’s teachings on creating successful arts organisations is the phrase ‘Great Art, Well Marketed’. Two exemplars of this were ‘Arabesque’, a three-week festival of art from Arab countries, and ‘Ragtime’, a new production of the 1998 musical. The former far exceeded forecast audience figures and the latter so successful that a fourth week was added.

Kaiser teaches and delivers fiscal prudence (he was responsible for turning around the fortunes of Kansas City Ballet, Alvin Ailey Dance Theater, American Ballet Theatre and the Royal Opera House) and as a result the Kennedy Center was in a very healthy position going into the recession. He has long offered free consultancy to US arts organisations but, as he watched the economy’s impact on the sector, he felt he had to do something more to help. Enlisting the support of senior Kennedy Center staff and calling on the wider sector as well, he launched ‘Arts in Crisis’, to assist struggling organisations with free planning and consultancy. This is another example of support for the arts being provided by the individual as opposed to the state. Ninety-eight arts professionals answered his call and they, along with Kaiser and his staff, are now mentoring over 350 organisations in 40 different states. On a personal level, this new programme gave a deeper insight into the challenges and opportunities faced by a much broader range of organisations and became yet another vital element of this invaluable fellowship year.

Cathy Hirschmann was a fellow at the John F Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and returns to the UK to take up the post of General Manager at Artichoke. Michael M Kaiser writes a regular blog, and his most recent book, ‘The Art of Turnaround: Creating and Maintaining Healthy Arts Organizations’ was published in 2008.

w: {www.kennedy-center.org/education}; {www.artichoke.uk.com}; {www.artsmanager.org}