David Jubb and David Micklem show how a renewed relationship with a local authority funder and new approach to making work can contribute to financial security.

For nearly 30 years, Battersea Arts Centre (BAC) has been inventing new ways of making and experiencing theatre. As well as recognising it as a theatre, local audiences may also know it as a place where they took their exams, attended youth theatre, got married, got drunk at the Battersea beer festival and attended a wake for an elderly relative. Not necessarily in that order. But in 2007, it faced an uncertain future and was on the brink of closing. In January of that year BAC received a letter from the council outlining its intention to charge rent and maintenance on Battersea’s Town Hall and cut the Service Level Agreement (renewed annually) to zero. Wandsworth Borough Council (WBC) stated that they “had been forced to make this difficult decision after [its] grant from central Government was cut in real terms by £5m, and [it was] told by ministers to concentrate on statutory services like schools and social services”.

The impact on BAC would be £370,000. And three months to find the cash. Things looked very bleak. During the dark days and darker nights of January and February 2007, the Executive and Board of BAC considered a future for the organisation out of Battersea’s Town Hall – indeed out of Battersea altogether. The relationship between WBC and BAC was at its lowest ebb.

Two years later in January 2009, as a result of innovative thinking by both BAC and WBC, and a desire to work together to overcome these funding problems, BAC is enjoying the first year of a 125-year lease on the Town Hall, of which the first 20 years are rent free. BAC and WBC are creating a four-year funding agreement in partnership, while in late 2008 BAC and WBC won Best Public Sector Partnership at the Third Sector Excellence Awards. Recently, BAC has also received an in-principle offer of £500,000 from the Community Assets Fund towards the development of its Town Hall home. The support of principal officers at WBC and Council Leader, Edward Lister, has been critical to these successes. The relationship now between BAC and WBC has never been better.

The crisis in 2007 brought three things in to focus.

Firstly, the relationship between BAC and its local community. In 2006 BAC had won the ‘Best Community Contribution Award’ at WBC’s annual awards for its schools’ programme, whilst the theatre’s local audience was one of the largest in the whole of London. The people who came out in support of BAC during 2007 were the teachers, local businesses and local families who benefited from BAC.

Secondly, the crisis meant BAC examined its relationship with its building, the Town Hall, concluding that the building was a key part of the organisation’s success. It had offered shape and form to a generation of artist’s work. BAC’s plans to develop the space (begun in 2006) were testament to this fact, aiming to open up the space and turn it back into a Town Hall rather than convert it in to a theatre.

Finally, the crisis brought a hugely improved dialogue with WBC. This was an opportunity for both sides to understand each other better. BAC’s Chair, Nick Starr, led negotiations which produced a great result for BAC. And a great result for WBC, because the Council will save millions of pounds of council tax payers’ money as it passes to BAC responsibility for the maintenance and development of the Town Hall.

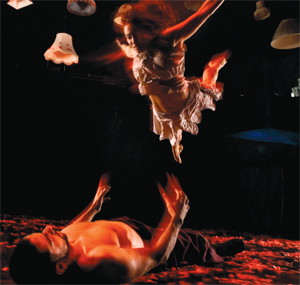

Perhaps the biggest lever in creating change was, satisfyingly, a piece of theatre. ‘The Masque of the Red Death’, a building-wide, site-specific, immersive theatrical event created by Punchdrunk in co-production with BAC, ran from September 2007 to April 2008 and was experienced by over 46,000 people. The project was BAC’s first ‘Playgrounding’ adventure. Playgrounding is a process developed over the last two years at BAC in collaboration with Steve Tompkins of Haworth Tompkins Architects. It transposes the principles of ‘Scratch’ (to take risks, respond to feedback and take time to develop ideas) to architecture. It is a human-centred design process of architectural improvisation that places artists and audiences at the centre of the architectural process. The Masque of the Red Death enabled BAC to reconsider completely its relationship with its home. It provided a catalyst for BAC to consider the entire footprint of its one-acre site for all its activity, opened up 20 spaces that were clogged with administration, storage or asbestos, and created design legacies from the show to benefit future visitors to the Town Hall. Our favourite is one room that now has a beautiful open fire, a space that has also become many visitors’ favourite in the building, a space in which we have programmed anything and everything at BAC.

Having secured our building, BAC’s challenge now is to raise the funds that deliver the full potential of a twenty-first century flexible performance environment across a nineteenth century Town Hall. The Playgrounding process will mean a slow-burn, phased approach to the refurbishment and improvement of the building. Whilst this way of working is rooted in a philosophical approach, it is also better suited to the challenges of recession and the depletion of public and private funding. We don’t under-estimate the challenges of delivering a multi-million pound project in such uncertain times but the last two years have shown everyone at BAC that it’s all possible.

David Jubb and David Micklem are the Joint Artistic Directors of Battersea Arts Centre.

e: artisticdirectors@bac.org.uk