The debate about the role that art can play in the built environment has evolved over the past few years. Phillip Dawson looks at the interface between art and the public realm.

If we are to believe the hype, todays arts practitioners live in an era of unrivalled opportunity; the ubiquitous carrot-on-stick of the Olympics in 2012 dangles above new hospitals, schools and sustainable communities. Even the greatest cynic would struggle not to acknowledge the feel-good factor in the world of art and architecture that, six years on, has to be more than a millennium high. Organisations such as Art & Architecture have long championed the benefits of a collaborative approach between artists and architects. More than 20 years since our inception, issues of authorship and ownership and use or ornament are still the subject of debate but is this progress?

Working the percentages

In our early years, we led the campaign for a percent for art; an objective partially achieved at a local level, with many authorities now incorporating arts policies as part of their Unitary Development Plans. This ensures that all schemes requiring planning permission provide a creative contribution to the public realm. Weve never had so many opportunities, say Art & Architecture members Phil Bews and Diane Gorvin, who describe themselves as jobbing sculptors having completed work on sites ranging from science parks to social housing. The percent for art framework means that in some sense, the battle has already been won. Crucially, the system provides a coherent artistic brief and a bridge between parties involved, helping to break down perceived notions of the artist as esoteric and unapproachable. But is the policy one of empowerment or imposition? Bews, who trained as a landscape architect, explains that the answer lies in changing thresholds of expectation: Twenty years ago we were fighting to include trees and plants within the streetscape today, many developers seem sanguine about the prospect of incorporating works of art.

In todays world of off-balance-sheet investment in the public sector, this policy now needs to be adapted by setting aside a percentage of capital costs we ignore important life-cycle costs of renewal and repair. Critics of the policy are quick to cite its limitations in encouraging true collaboration: the commissioning process is often retrospective, running alongside, and not before, design development. Perhaps this criticism is in itself indicative of progress a sign that the debate has moved on from questions of awareness, budget and leadership, to issues of professionalism, programme and process. Maybe the fact that a director of a firm of architects is author of this article is testament to this evolution?

Those anxious to see a closer relationship between art and architecture have been encouraged by the completion of major public buildings where artist and architect have been players in the cast: Sir Terry Farrell and Liam Gillicks Home Office and the West Wing at St Bartholomews Hospital are both projects that have received critical acclaim. What links these successful collaborations are excellent management from client and developer, educated and experienced practitioners, and a clear framework for defining the responsibilities of both artists and architects.

Blurring the lines

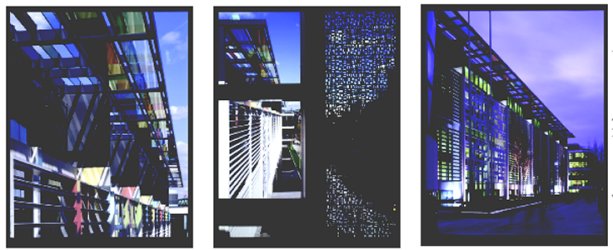

But a clear cut division-of-labour isnt the only approach. In December, Art & Architecture heard from Niall McLaughlin and Martin Richman. Their most recent work, public housing at Silvertown Quays, is characterised by the use of iridescent film within the glazing, a diachronic motif echoing the chemical history of this docklands site. Throughout the project, the relationship between art and architecture has been blurred, any judgement on authorship rendered impossible. Is this the summit of collaborative endeavour?

The idea of the architect being master of the building has to be let go, says McLaughlin. Set up by way of a blind date masterminded by the curator of the Royal Institute of British Architects Gallery in 1997, the artist and architect then created a strategy for ego management not to suppress ideas, but to facilitate the acceptance that both partners could contribute to a better design; a process they describe as deferred gratification with the aim of outflanking visual prejudices. After recognising inhibitions of ego and professional pride and overcoming the technicalities of insurance and copyright, pragmatic partnerships, such as those embodied by McLaughlin and Richman, can open doors creatively and practically, but can there be a danger of too much empathy? Does the very process of achieving this level of self-actualisation carry with it the potential to limit creativity?

Beyond privilege

In todays network society, artists and architects seeking a professional union can now draw on a wide range of information outlets. Access to new opportunities (for both artistic and architectural competitions) has improved. Our own organisation has transformed to meet this need; the Practitioners Network page on the Art & Architecture website is something of an intellectual dating service, and on the links page there are countless design guides from organisations reinforcing the importance of art in the public realm.

However, art in public places remains in a policy vacuum at a national level and thus occupies the front line of cultural politics the Trafalgar Square plinth clocking up precious column inches and the question of how to measure public value ever present. With talk on the Clapham Omnibus preoccupied by issues of poverty and the environment, any debate on contemporary art navigates the narrow path around connotations of privilege and élitism: Gormleys cultural cringe. Perhaps partly in response, we have adopted a language of urbanism, but changing semantics alone cannot advance the professionalisation of artists.

The children of the Me Decade, now our legislators, are candid about their desire for creating a legacy: the soundbite of our successful Olympic bid. The Secretary of State for Culture referred to the public realm as living democratic spaces, rationalising the need for investment through the promotion of good citizenship in a speech intellectualised by Sennetts Fall of Public Man. But should the practitioner of public art be seen as purveyor of high culture or freelance sociologist? Is calculating the social worth of public art a method of taming cultural cringe or is it a product of it?

Value

In our developing technocracy, the value of art and design is no longer axiomatic. Inevitably, someone must ask is it worth it? How do we value the benefit of art in the public realm? In a study published last November, researchers from Edinburgh College of Art have developed an impact evaluation matrix based around artistic, social, environmental and economic criteria. The authors take care to point out that impact and value are not mutually exclusive; nevertheless, by evaluating the objects of public art as a means to an end are we not ignoring the importance of artistic potential? Is the greatest value not in the objects themselves, but in the creative endeavour the true legacy of training, education and experience? After all, the rise and fall of the public realm is dependent on the engagement of our diverse and renewable artistic resources.

Whatever the desires of our civic leaders, they rely on the machinery of state. With the security of private patronage consigned to the last century, commissioning structures exist in an age of evidence-based policy in our risk-averse society. No matter how we define the value of art and design, nor how professional artists and architects become in their approach, it is track record that counts in the public sector. Recent research by Art & Architecture revealed that 94% of public architectural competitions advertised through the EU were won by large, established practices of 10 years standing or more. In the game of innovation, our opponent is the unknown. Public sector commissioners must be freed to take intelligent risks.

We now seem to be fighting two battles one of advocacy for the promotion of artistic activity in the public realm, the other to ensure a level playing field for all practitioners. But perhaps the biggest issue facing us all over the next few years will be whether the public sector can continue to be a guardian of cultural democracy in an age of devolved and consensus-led politics.

Phillip Dawson is a Director of Fraser Brown MacKenna Architects, and Membership Secretary of Art & Architecture. Art & Architecture is an independent association providing an infrastructure to enable cross-discipline collaborations.

t: 020 7251 0543;

e: ped@fbmarchitects.com;

w: http://www.artandarchitecture.co.uk