In commercial organisations and even in other not-for-profit sectors, evaluation tends to be seen as part of a dynamic, on-going process; something that guides, influences, and even inspires. Why then is it seen as such a chore for the arts? The Cultural Policy and Management Group at De Montfort University consider why evaluation is misunderstood and how it can be an effective management tool for arts and cultural organisations.

There?s something final about evaluation in the arts. It?s the last question on the funding application form. It?s what you do at the end of a project to release the remaining money. But shouldn?t evaluation be an integral part of the strategic planning process, rather than just a necessary evil?

Shock tactics

Let?s cast our minds back to the mid-80?s when the arts first encountered strategic planning. What a shock that was. Until then the arts had largely subscribed to Sir John Harvey-Jones?s view of planning: ?Planning is an unnatural process; it?s much more fun to do something else. The nicest thing about not planning is that failure comes as a complete surprise, rather than being preceded by a period of worry and depression?.

Of course once you had a plan you were required to prove that you had successfully achieved what you had set out to do. Thus evaluation became the next requirement and nobody, practitioners or funders, knew quite how to go about it. Faced with the pressure to be accountable, they grasped the first available evaluation tools that would prove the effectiveness of their strategies. But to some extent the structures they adopted, which were largely quantifiable, have worked against the development of a more holistic approach to evaluation.

Why evaluate?

Making a judgement about the value or impact of a particular policy, objective or strategy deserves much more than quantitative evaluation. It is about much more than counting the number of people who attended or the number of responses: it?s about learning and improvement. To evaluate is to make a judgement, based on evidence, about the value, quality and worth of something. It can tell you what happened, and importantly, it can tell what is actually happening now; but only if it is built into the planning process from the outset. Evaluation needs to take place at every stage of strategic planning in a relevant way, using appropriate methodology; and there is a balance to be struck between simple ?hoop jumping? and the ?evaluation paralysis? that Peter Hewitt alluded to in his keynote speech ?Beyond Boundaries? last month.

Collaborative approaches

Reaching a judgement about the value of something isn?t easy and it?s worth remembering that there may be many different views and perspectives that need to be considered. We advocate a broader approach to evaluation that encompasses a range of views and experiences, both internal and external to the organisation. Social, cultural and political factors are integral components in the evaluation process. For example evaluating work with culturally diverse communities requires sensitivity, and a range of issues must be considered: the need for staff training in cross-cultural awareness, the degree to which culturally diverse communities are part of the decision making process, and the extent to which formal and informal networks have been established. Culturally sensitive evaluation methods should accompany culturally sensitive programming. We have found that evaluation undertaken in a collaborative way, involving all stakeholders, produces more meaningful and useful information. Vital to evaluation is the notion of it as a learning process; something that will lead to improvement, stronger organisations, and better art.

New directions

Some of the most important research and writing in the development of evaluation has been undertaken by Guba and Lincoln (1989).Their model of evaluation is based on the proposition that evaluation should be ?mutually educative? and if you are undertaking evaluation you should be prepared for unexpected outcomes. They advocate new goals for evaluation, based on the premise that evaluation should be:

? a socio-political process

? collaborative

? teaching and learning focussed

? continuous

? an emergent process (i.e. unpredictable)

? a process that creates reality

The consequences of these new goals mean a variety of views are tolerated. Accountability produces shared responsibility and empowerment; not having an evaluation ?done to you? but actually being part of it.

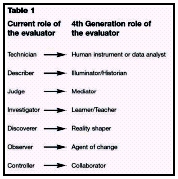

Given the tendency today to engage independent evaluators, we need also to consider their role in the process. It is common for evaluators to be greeted with suspicion, even outward hostility, by the organisations they evaluate. Guba and Lincoln have reinterpreted the many roles of the evaluator, believing that this will lead to more meaningful evaluations, regardless of whether the evaluator is independent or in-house. This change of emphasis turns what might be a passive process into a very powerful and empowering management tool, a notion of evaluation as an integrated process rather something done at the end of a project or period of time.

The future

Despite the protestations of many in the arts, evaluation is here to stay. The sector needs to learn much more about evaluation techniques and create systems that become an integral part of the strategic planning process. Evaluation is at its best when it is an interactive process and needs to be flexible and responsive, honest and open. The sector needs to invest in research, development and training. (How many RALP organisational development awards have focussed on developing effective systems for evaluation?).The rewards are not pieces of paper or numbers, they are empowerment and organisational growth.

The Cultural Policy and Management Group at De Montfort University includes Franco Bianchini, Christopher Maughan, Diana Walters, Tony Graves, Michèle Taylor and Jan Ford. The Group is currently undertaking a range of research projects for regional, national and international arts and cultural organisations. Contact Diana Walters e: dwalters@dmu.ac.uk