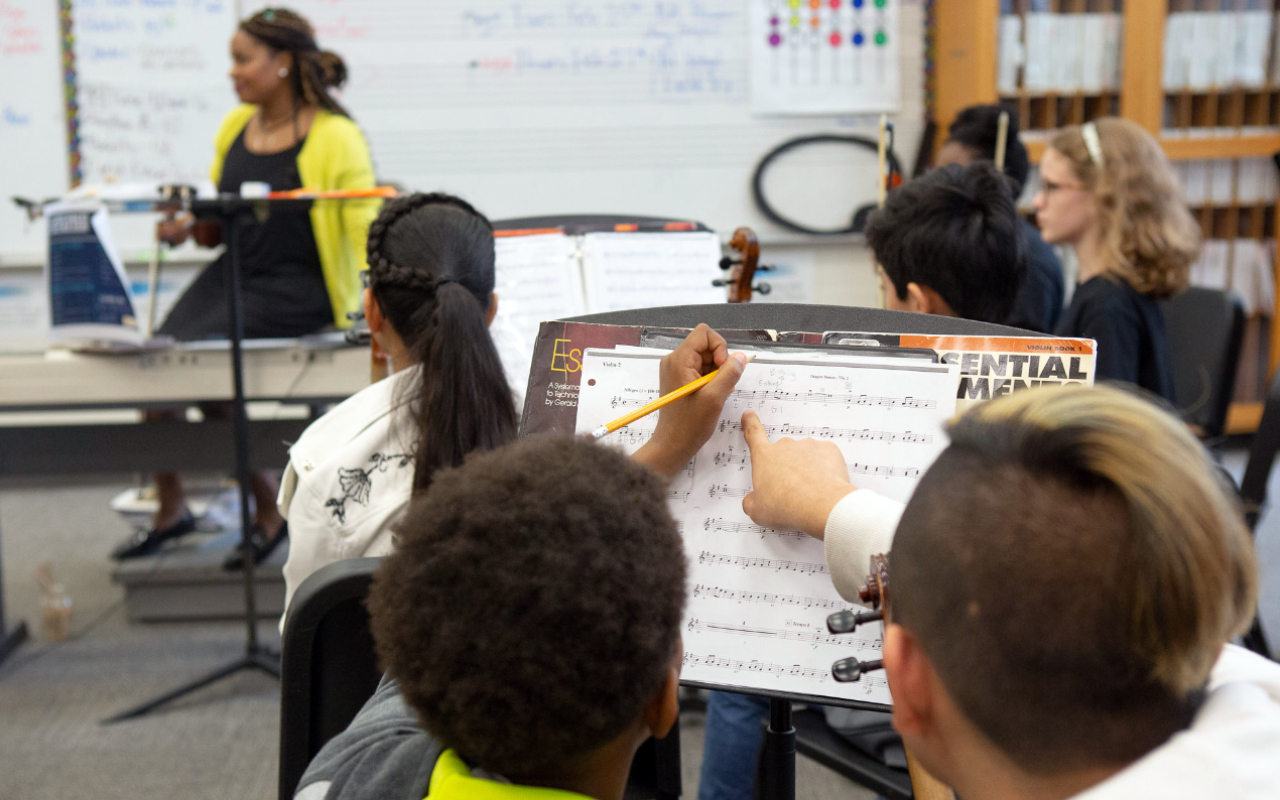

Make music compulsory in schools, says refreshed plan

The updated national plan for music education offers a renewed focus on schools but falls short of addressing all concerns raised over the last decade.

The government’s refreshed National Plan for Music Education (NPME) in England says music should be a key part of the school curriculum.

The long-awaited revision offers an update on the original plan published in 2011 and sets out a vision for music education to 2030. Admitting the current music education delivery in England is “patchy”, the update emphasises the role of schools in delivering music education, calling on every school to draft its own music development plan to ensure high-quality provision for all pupils.

The Musician’s Union (MU) says the plan is “the most coherent description of a vision for music education in England that the government has provided to date”.

READ MORE:

“While specialists in individual areas may well take issue with details, the totality of what is described – were it to happen – would lead to significant improvements,” the union said.

All pupils up to year nine should have at least one hour per week of “high quality” music lessons as part of the curriculum, according to the plan.

The requirement aims to bridge a gap in music education delivery for Key Stage 3 pupils. A survey by Teacher Tapp released earlier this week found 22% of secondary school teachers said year nine pupils receive no compulsory music lessons, and a further 13% said they only study music for part of the year.

Under new guidelines, schools are expected to have a choir and/or vocal ensemble, facilities for rehearsals and individual practice, and offer opportunities for live performance at least annually and a school performance each term.

The plan is extended to early years and further and higher education for the first time, asking early years practitioners to “build a musical culture and identify potential” and for secondary schools to recognise formal music qualifications as one way for pupils to unlock careers in music.

Music Education Hubs, which were established in 2012 following the publication of the first NPME, must develop an inclusion strategy, appoint an inclusion leader, and develop a local plan for music education in tandem with a small number of lead schools by spring 2024.

An open retendering process for the lead organisation of music hubs is planned, with the government hoping this will lead to fewer hubs covering wider areas. Arts Council England will remain the fundholder for hubs.

Although schools have been told to implement measures from the start of the next academic year, with the Department for Education (DfE) saying it will “monitor progress”, the guidance for schools is ultimately non-statutory.

In contrast, hubs will be expected to deliver on some outcomes as part of funding agreements, which the MU says is “particularly concerning”.

“This potentially sets up a clash between hubs and schools and would benefit from further clarification,” the union commented.

New fund for instruments

Tens of thousands of pupils will get the chance to learn a musical instrument, through a £25m fund for schools to purchase instruments and equipment.

The DfE estimates the money will make around 200,000 new instruments available, including adapted instruments for pupils with special educational needs and disabilities.

Further support is expected through a Music Progression Fund, designed to support disadvantaged pupils with significant musical potential, by autumn 2023, and four new Centres of Excellence, based in music hubs, by autumn 2024.

But the plan stops short of replicating Scotland’s commitment to abolishing music tuition fees in schools altogether.

Bath Festival Orchestra’s Education Manager Helen Kuby said the added investment is “particularly encouraging [for] executing the pragmatic nature of music education systems”.

Music Mark CEO Bridget Whyte agreed, adding a key role for the music education association will be to “help those who may be seeing problems and challenges ahead, particularly teachers and school leaders who are already overstretched”.

Concerns remain

The MU says the DfE’s decision to keep annual funding at £79m until 2025 marks a “significant real-terms cut”.

Funding levels have been roughly the same for the last decade, leading to concerns that music hubs will be asked to do more for less.

The plan is also without promise of reviewing pay and conditions for music teachers as outlined in Wales’ edition last month.

Paul Smith, CEO of choral music education charity VOCES8 Foundation, told ArtsProfessional “there is a huge amount to do” to get music going again in schools post-pandemic.

“The government gave unprecedented levels of support to help artists and arts organisations survive the pandemic, but it is critical now that we continue with investment in the future as well.

“What’s the point in surviving the pandemic if we can’t find the funding to help children in the future?”

Incorporated Society of Musicians (ISM) Chief Executive Deborah Annetts largely welcomed the content of the plan but added it could be improved “if music teachers, parents and other experts had the opportunity to provide their views through an official consultation”, as once promised by the DfE.

The plan does not touch upon reforming accountability measures such as the EBacc and Progress 8, which a recent ISM report found to have contributed to the decline in music education in schools over the last decade.

“To really grow music in schools, we need urgent reform to accountability measures and greater funding for music in schools,” Annetts added.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.