'Decolonising the curriculum' has become a touchstone for educational institutions. But what does this mean in practice? Clare Connor and Lise Uytterhoeven examine the changes ahead.

2020 was not just about a virus but an awakening. Covid-19 and the Black Lives Matter protests exposed injustices in our society on a major scale. While the pandemic has undoubtedly sent shockwaves through our institutions, we believe the fight against systemic racism is the greater challenge of our time. Our young people deserve far better from us than cosmetic changes to a system that isn’t serving them and that our students, many of whom are deeply involved in activism, unequivocally reject.

A new world of work

As London Contemporary Dance School, ‘contemporary’ is woven into our DNA. It is our heritage as a pioneering arts school to experiment and innovate, continuously questioning what ‘contemporary’ means and whether we must adapt to meet its expectations. In preparation for last year’s periodic programme review – a five-yearly process to reinvigorate programmes – the team at LCDS spent two years listening to students, artists, audiences and industry leaders to understand the conditions needed for growth and the changes the industry wanted.

The dance world has changed dramatically, and not just because of the pandemic. The days when dance students used higher education to condition themselves for a specific company’s aesthetic (and the dream of national tours and equity pay throughout their career) are truly over. Our graduates face a cultural landscape they will go on to shape, meaning the skillset required to build a sustainable career in the arts is quite different to that of the past. Our duty is to prepare them to be confident, versatile and independent artists who will drive innovation in dance, expertly collaborate with other art disciplines, and act with an entrepreneurialism that befits the 21st Century economy by embracing what the artform can contribute to society at large.

Diversity in decolonisation

Diversifying the dance curriculum isn’t an exercise in virtue signalling or jumping on a social media trend; it is an essential step to enable our graduates to find their own artistic voice and forge sustainable careers.

Decolonising is complicated. It means facing our colonial past, questioning our ideas of normal, where we have historically placed value and why. For institutions, it means taking a hard look at the culture of dance we have created and the image of the dance world we present to our students. Why is it that ballet and contemporary techniques are held in higher regard than kathak or hip hop or vogueing? How can we decentralise that hierarchy and expose students to a greater variety of practices? We want them to be able to anchor their artistic practice in the tools and techniques that speak to them the most.

Important lessons can be learned from the dance practices that have so far been missing in institutions. Jane Chan, one of a team of new guest lecturers, says: “Kathak introduces the students to a different way of moving, a different relationship with music and rhythm that has been really beneficial to me as an artist in finding my own movement language.” Arran Green, who has a background in capoeira, breaking and the wider hip hop culture, compares their movement choices to musical disciplines such as jazz, where inspiration and improvisation are based on technique and an awareness of the choices you can make within the genre’s parameters. “In other cultures such as ballet, the reason for a movement is often for someone to view it. In hip hop culture the objective is the actual dancer as the one who is generating and using these moves. It’s a different way of sharing knowledge, a different psychology behind what's important, but both are equally valid and valuable for students to learn.”

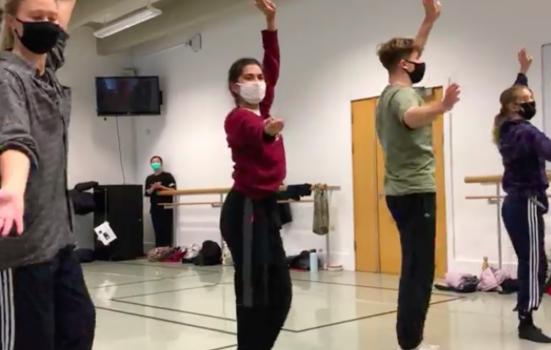

How we do it

Another way of decolonising is creating fair and equal opportunities. The traditional audition process where a panel of staff judge applicants by their talent feels flawed. We take talent to mean the innate ability to do something well when it is actually a carefully constructed and nurtured development of skills and tastes, usually through paid-for classes, training opportunities and cultural capital – things that are not readily available to applicants from disadvantaged backgrounds. What we really need to look for is potential and an openness to engage with movement and conceptual ideas. Our new process of video applications and an admissions workshop is more inclusive, giving people from varied backgrounds a voice in how they present themselves to us. We are hoping that people who may have felt they wouldn’t fit at LCDS will now feel encouraged to apply.

Of course, we couldn’t simply diversify the dance curriculum without also addressing the way we assess. A big key to decolonising is removing the system which defines success as fitting a certain mould. We must stop measuring the aesthetics of what students produce against an invisible standard of excellence. No two students will look the same. We want to open space for all bodies and look at the quality of what each artist can contribute to the wider world. Our new mode of a portfolio assessment, borrowed from our new validating partner University of the Arts London, lets students choose whatever best represents them or their interests, play to their personal strengths and hopefully empower diversity in dance.

We are rethinking how our whole organisation operates, incorporating more open calls in our theatre programme, more inclusive selection and recruitment practices, unconscious bias and anti-racism training. We plan to create two new lecturer roles focusing on dance practices from the global south. These changes are a work in progress and will take time. Decolonisation doesn’t happen in a silo, and there are big questions and imbalances we need to address as a society. We have to take responsibility now and educate ourselves. Ultimately, the decolonisation of dance will happen in the minds of the students we educate and the world they will go on to create. We are building the environment for them to thrive – they will be the change.

Clare Connor is Chief Executive and Lise Uytterhoeven is Director of Dance Studies at The Place