The Scottish Government’s Spending Review and Draft Budget for 2012/13 contains some difficult news for the arts, both directly and indirectly. Anne Bonnar delves into the detail

The Scottish Government’s spending plans, announced on 21 September, were managed in what is now becoming its customary style, where it celebrates its successes, takes a pot shot at Westminster and gently avoids declaring any bad news. In the days following the budget, independent analysts, journalists and professional associations affected by the budget announcements have got out their calculators, shared the full impact of the cuts and hikes in business rates, and predicted a severely negative impact on local government services in particular.

The Spending Review is fulsome in its description of successful achievements, including in the arts and culture, and in particular those activities which make an obvious contribution to the Scottish Government’s single Purpose – economic growth. Edinburgh’s festivals and international touring are specifically applauded for their contribution to Scotland’s international reputation, and the creative industries are recognised as being one of the nation’s growth economies.

It also kicks off with an analysis of the settlement from Westminster, blaming it for the scale of the cuts, pointing out that the cut amounts to 12.3% in real terms over the next four years. This is fodder for the arguments that Scotland needs more fiscal autonomy to succeed. It then highlights the achievements of the Government and focuses on good news. The figures are arranged for display through several lenses with the clearest being the three-year figures in real terms.

Real terms take into account the impact of inflation. Much of public sector budgets are tied up in rising salaries and in the escalating costs of gas, electricity and transport and these costs will be met before any other expenditure. This will hit the arts particularly hard. Unlike social work or the health service or teaching, for example, the salaried workers in the arts are not the ones who deliver the life-changing experiences. It is artists, prop makers, musicians and dancers, who are nearly all self-employed freelancers, and for whom there will be proportionately less cash after the cuts in real terms have been used to pay salaries and operating overheads.

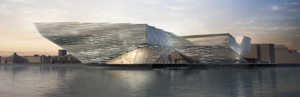

There are some good news stories for culture in Scotland: there will be capital expenditure on the V & A in Dundee and two Glasgow venues, justified because of their role in the forthcoming Commonwealth Games. There is the preservation of international touring and Expo funds, and the ringfencing of funds for some favoured initiatives, in particular the Youth Music Initiative and Arts and Business. A new initiative for young people has been announced within the culture portfolio, with £54m for sport, creativity and culture. But behind the smoke and mirrors, the direct cuts to culture are moderately severe and are higher than to most other Government Departments, with the percentage of the overall Government budget allocated to culture reducing from 0.59% in 2010/11 to 0.50% in 2014/15. Next year, 2012/13, there is a decrease in the culture budget of £5.4 m, which is 3.6%. In real terms this is 5.9% or £9.1m.

For Creative Scotland, there is a 2% cut in core revenue while other initiatives favoured by the Government are ringfenced. At £10m a year, the Youth Music Initiative is the most significant of these. This means that, after the ringfencing and the commitments already made by Creative Scotland in its corporate plan, the funds designated for strategic commissioning are likely to take the hit. This strategic commissioning fund is shown in the corporate plan as being £7m, and replaces the £8m currently allocated to flexibly funded organisations – including many small and medium sized arts organisations. If this fund bears the full blow of the 2%, it will be down by about £800,000 – in real cash.

The financial implications for local government are being hotly disputed by independent think tanks and both levels of government. The settlement is complex, with the ringfencing of some costs for teachers’ pensions for example and additionally there is the impact of a projected major hike in revenues raised from business rates. COSLA, the local authority association, has responded to the cuts angrily, accusing the Government of sleight of hand and spinning the facts. They predict major cuts to services and the Scottish Goverment’s projections for hiking these up are stirring controversy. This bodes darkly for culture. Culture is not a statutory obligation on councils and councils are not asked specifically to support culture, which is noticably absent from the Performance Framework. Government’s own justification for spending on culture is for its instrumental benefits to other, often economic, outcomes.

Without a requirement to provide for participation in culture locally through the outcome agreements, the arts and culture are significantly exposed.

The Scottish Government are masters at managing the show and on past performance they are likely to produce a dazzling diversion from the bad news. Will they pull the rabbit out of the hat in the shape of additional lottery funds for Creative Scotland to spend? Possibly. But that will not be a substitute for local authority cuts.