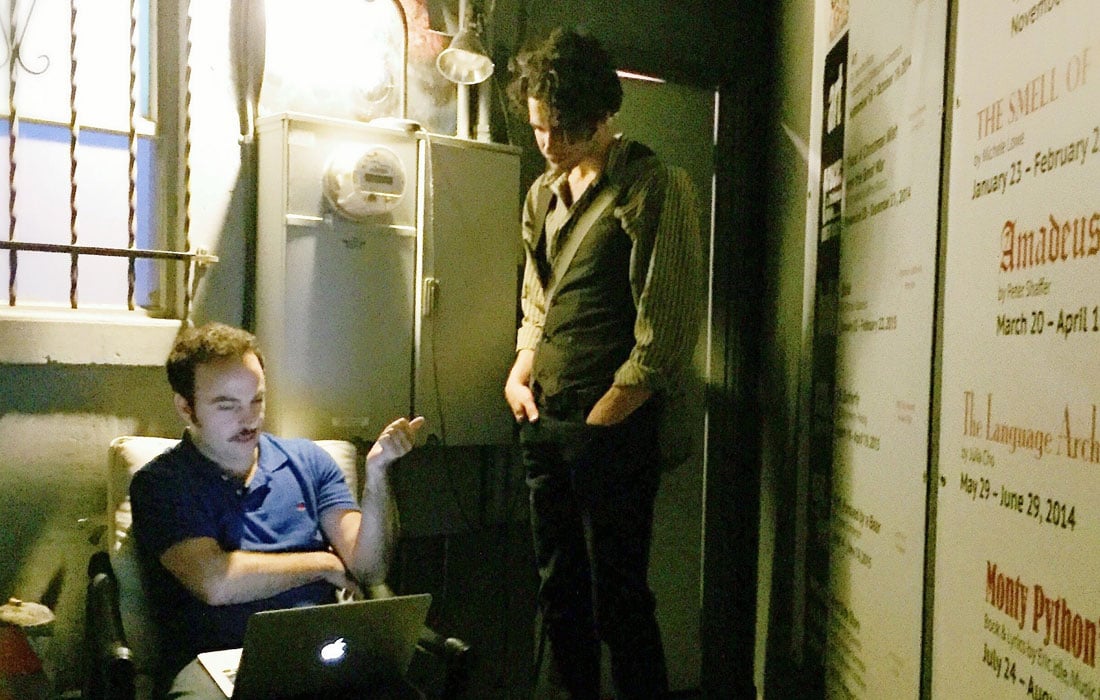

George Psarras (Dr Jekyll) and Adam Magill (one of four actors playing Mr Hyde) discuss a question

The talk of the town

When Ron Evans started thinking about how to make post-show talks more appealing and accessible, he found audiences hungry for new ways of engaging with the arts.

“You’re all set. As soon as a text comes in, it’ll show up on the screen and you can respond.” I was leaning over the shoulder of George Psarras, the lead actor in Jeffrey Hatcher’s adaptation of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, as I gave him a quick tour of the software. It was minutes after the show. Hastily changed into street clothes, he still had beads of perspiration on his forehead.

Once the texting discussion began, it was hard to keep up with the questions

The first text from an audience member came in: “Fascinating production. I’ve never seen multiple actors play Edward Hyde in the same show. Was it challenging working with other actors who had different interpretations of the role?” “Interesting,” George muttered, as he started to type back.

Audience engagement

It was a post-show talk unlike any the theatre had ever put on. And that was the point. Using a grant from Silicon Valley Creates, City Lights Theater Company in San Jose, California brought me on-board to experiment with new ways of delivering that staple of audience engagement: the post-show talk.

It’s widely agreed that these opportunities to discuss a show in more detail bring many benefits. They help people make meaning of the performance they’ve just experienced. They create a space to ask questions. And they offer the pleasure of exploring a work with like-minded theatre-goers. Why mess with a good thing? To dramatically improve the concept, of course.

The traditional talk presents challenges. Many people can’t stay after a performance as they need to get home for babysitters or they have a bus or train to catch. And the obvious: people have been sitting in their theatre seats for two hours, and now they are being asked to sit longer.

At the first ideas session, one possibility quickly became clear: the post-show talk could survive, and even thrive, outside the confines of the physical venue. And offer intriguing new experiences for audience members.

Three experiments

I designed three experiments for alternative forms of post-show talks. For the first, rather than bringing cast and artistic staff on-stage to discuss the current play, we planned an innovative event promoting the next show in the season.

After a matinee performance we rolled out a large television in front of the audience and connected it via Skype to the playwright of the next show. She greeted the audience, gave a quick synopsis, and talked about her inspiration for the play, taking questions as she went. On their way out, audience members commented on how rare it was to be able to speak to a playwright, and how they planned to attend the next show. That’s exactly what I wanted to hear.

The second experiment was designed around how might people participate in a talkback, but from outside the theatre. Almost everyone has called into an audio conference call. In Silicon Valley, it’s a daily occurrence. But that’s business, not theatre. Would audiences respond?

House managers provided slips of paper to each of the 100-plus audience members attending that day, inviting them to call in to a conference number 30 minutes after the show to chat with the director and one of the lead actors of the production of the classic musical West Side Story. And they did. Some asked questions, and others just listened. We recorded the whole thing and shared it with audience members from other performances.

The third experiment explored taking post-show talks into the world of text messaging as I’ve described above. Using a service called Pinger.com, I set up a texting account to hide the mobile number of our lead actor and distributed the invitation to audience members.

Once the texting discussion began, it was hard to keep up with the questions. In all, 14 participants asked 18 questions about the production, motivations of the characters and meaning of plot points. Other actors gathered around the screen and ended up breaking into sub-conversations themselves. In the end, both audience members and actors reported enjoying the fresh approach to the post-show talk, from the personal connection of their own phone.

New technology

City Lights Theater Company had multiple goals for these experiments. For example, they asked me to advise them on the most effective ways of gauging the interest of their audiences in non-traditional post-show talk formats. We also felt that experimenting with new technology and communication channels might reduce barriers to participation, and that this new participation would deepen the emotional experience of attending. That’s a brilliant formula to lead to future attendance.

These experiments also made the content more accessible, as audiences who have attended any performance can participate in a conference call or text talk. Talks can be recorded and shared with audiences attending later in the run. A recorded talk is archived proof of audiences deeply engaging with the arts organisation. That’s something funders absolutely adore.

In the end, it’s clear that audiences continue to be hungry for new and interesting ways of engaging with the arts. Even the simple act of inviting audiences to be part of trying something new seems to encourage participation.

Ron Evans is a strategic arts advisor working in the US.

askronevans.com

Tw @askronevans

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.