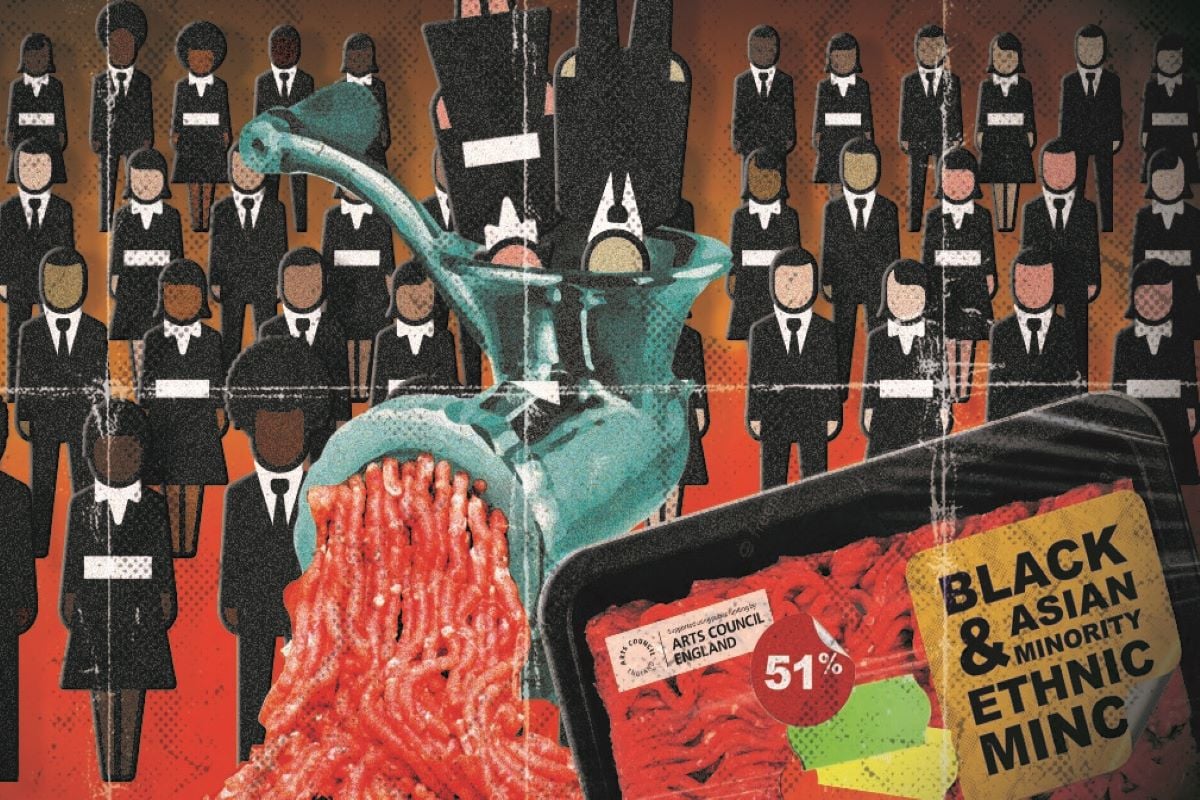

Image by Paul Ayre

Diversity data: colour or ethnicity?

With all the ambiguity around ethnicity terminology, Kevin Osborne is gradually coming to the view that identifying people by their colour is the best way to drive race equity.

Arts Council England (ACE)’s new National Portfolio investment 2023-26 will increase funding to racially diverse-led organisations from 2.4% to 8.4% (£37.67m per annum). If it materialises, this would be a meaningful step towards meeting its own commitment to allocate funding in a racially equitable way, in line with England’s racial diversity (18.3%).

But there is a significant challenge in testing ACE’s commitment to diversity because the term BAME* (or Black, Asian and ethnic minority) is not clearcut: it can refer to exclusively non-white communities (i.e. Black and Asian groups) or to communities which include white ethnic minorities. Each interpretation yields very different results, particularly in terms of assessing the level of funding of Black and Asian-led organisations.

For illustration: the term BAME has different meanings (or emphases) depending on whether it’s used as an acronym or is disaggregated. According to the Law Society’s guide to race and ethnicity terminology and language, the BAME acronym typically means non-white minority ethnic communities.

However, in recent years, many institutions – including ACE – have dropped the term BAME in in favour of the full wording: Black, Asian and minority ethnic. Again, according to the Law Society, the term ‘minority ethnic’ includes predominantly white ethnic groups such as Polish, Irish, Gypsy and Roma**.

BAME ≠ Black, Asian and minority ethnic

So, the two definitions are at odds. While the acronym BAME mostly refers to a group’s colour and to people of Black and Asian heritage, when disaggregated, it can be interpreted as referring to all ethnicities, including white ethnic minorities.

From a legal standpoint, anyone Polish, Irish, Jewish, Gypsy or Roma can choose to be from an ethnic minority. Funders can therefore consider an organisation in which these minorities represent 51% or more of the leadership team as diverse led, which allows them to be counted as part of ACE’s headline racial diversity figures.

To date there has been no transparency from ACE on which organisations in the National Portfolio are considered diverse led. Neither is there any clarity on whether ACE’s interpretation of ‘Black, Asian and minority ethnic’ includes white ethnic groups – or not.

The need for transparency

The problem of race and ethnicity terminology is well illustrated in an article about the BBC’s interpretation of the term BAME. In 2017, the corporation decided to exclude Jewish presenters from its list of the top 20 best paid presenters.

Had the BBC chosen to include white ethnic minority groups, it could have claimed ethnically diverse presenters were over-represented, at 20%. The decision to focus on colour rather than ethnicity meant the statistic they arrived at was 0%. So, it’s critical to have transparency about what’s being measured: ethnicity or colour.

We were able to interrogate the BBC’s claims because the data are published in the public domain with full visibility for anyone who wishes to look. We know how the BBC presents race and ethnicity data.

The same is not true of ACE’s National Portfolio where we are in the dark about which funding recipients are included in its statistics on diverse-led organisations. This is important because, with ambiguous definitions and interpretations, organisations like Southbank Centre, for example, could potentially be considered diverse led. If that were the case, as an NPO in receipt of substantial funding (£16.8m p/a) it would drastically skew the headline diversity figures.

Colour vs ethnicity

I think I have demonstrated the need for complete clarity and consistency across all agencies about the term ‘Black, Asian and minority ethnic’ (BAME) and whether it includes or excludes white ethnic minorities.

If we want the term BAME to be colour neutral (inclusive of white ethnic groups) – in effect to mean non-white British – we must find ways to acknowledge skin colour as it is still one of the most pervasive forms of discrimination in the UK today. We need to be able to disaggregate Black and Asian from the ‘Black, Asian and minority ethnic’ data in diversity reports.

While we await uniformity in the terminology to describe ethnic groups, funders need to be transparent about which ethnic groups are included in their diversity statistics and provide details of who is funded in that category. That way, claims can be checked, and trust developed.

Any attempt by ACE – or others – to hide behind ONS guidelines or GDPR rules when deciding what information should be made public, would only further exacerbate racial discrimination and colour bias in our system.

Anonymity is a white privilege

Black and Asian people have no choice about being identified as an ethnic minority; they are identifiable by their colour. People from a white ethnic minority can remain anonymous if they choose. In terms of racially equitable funding, privacy laws and guidelines not only prevent full transparency, but they are a perfect example of colour bias in our system. Anonymity is a white privilege.

I call on ACE to make public the top 100 (c.10%) highest-funded NPOs, just as the BBC was required to do with its top-paid presenters. If the BBC overcame issues of privacy /GDPR in the public interest, the same should be true and possible for ACE.

Creating a hierarchy of ethnicity would not be helpful. What I’m calling for is simply greater transparency so we can better analyse diversity data and hold funders to account about them. It would not help only ethnic minority groups, it would also help ACE achieve its diversity targets through strategic, evidenced and targeted intervention wherever necessary.

Kevin Osborne is CEO at MeWe360 and Create Equity.

![]() @_KevinOsborne | @mewe360 | @createequityuk

@_KevinOsborne | @mewe360 | @createequityuk

![]() createequityuk.com | mewe360.com

createequityuk.com | mewe360.com

*We recognise the diversity of individual identities and lived experiences and understand that various terms used in this piece to describe ethnicity are imperfect and do not fully capture the racial, cultural and ethnic identities of people that experience structural and systematic inequality.

**All these groups are ethnic minorities. However, there is no tick box on the census for some of these groups and they have to choose to disclose their ethnicity.

This article from social entrepreneur Kevin Osborne, founder of MeWe360 and Create Equity, is part of a series of articles that promote a more equitable and representative sector.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.