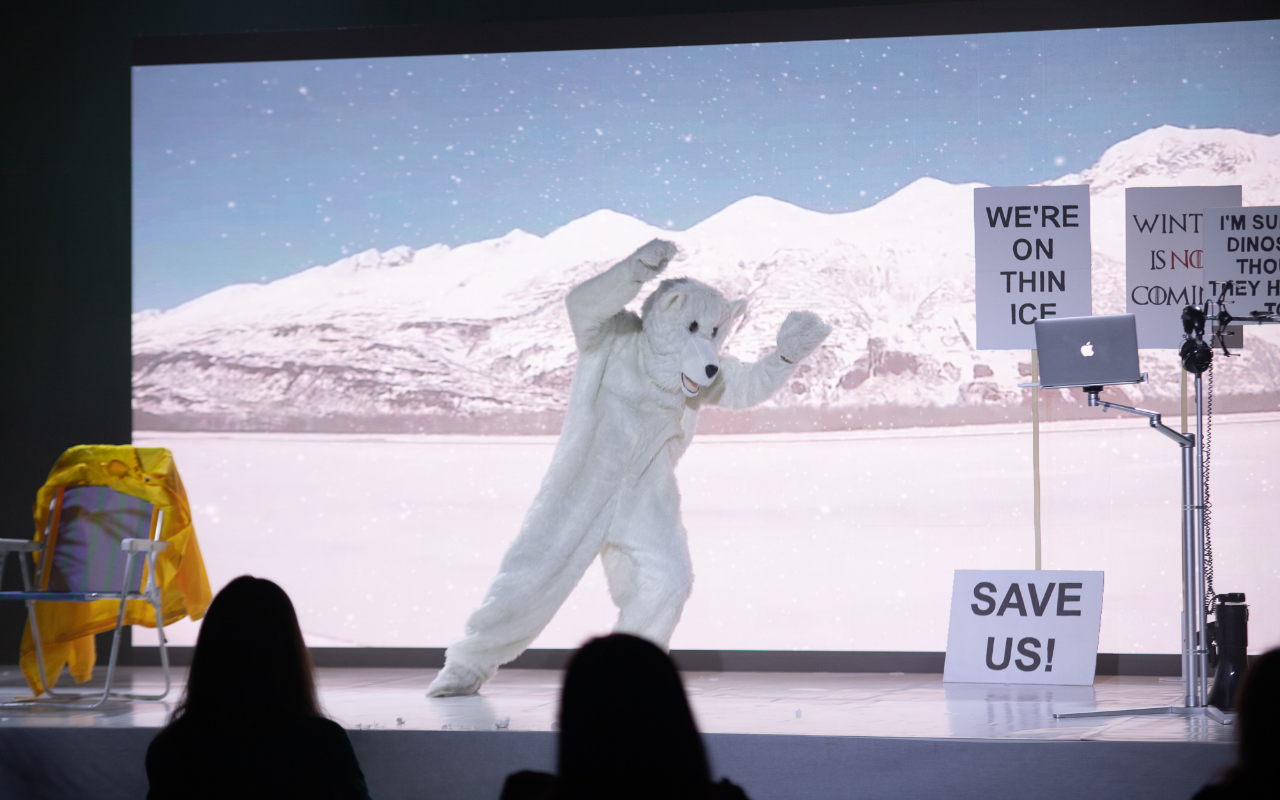

The Polar Bear (is Dead) created by Natalie Bellingham and Daniele Pennati, presented by Creative Wakefield.

Photo: Ash Scott

Can corporate sponsorship be part of the environmental agenda?

As arts organisations struggle with post-Covid recovery, Michelle Wright asks whether sponsorship can grow in this economic climate.

The question of whether corporate sponsorship can develop is vital as we recover from Covid and grapple with other agendas such as Black Live Matters and the climate emergency. The COP26 climate summit in Glasgow is a case in point. The event has been very popular with sponsors with names such as Microsoft, Unilever and GSK represented.

However, for a conference aimed at bringing 100 national leaders together as a last chance to find ways to limit global warming, as well as the opportunity for the UK Government to unveil plans to meet its net zero target by 2035, the presence of corporate sponsors seems particularly difficult. With sponsorship heavily linked to marketing Return on Investment, the corporate presence seems immoral when we consider the contribution to global warming driven by corporate consumption.

Of course, this COP summit isn’t an exception; previous summits have had sponsors as well. Corporates represented at the 2015 Paris summit were estimated to have contributed almost £18m (about 10% of costs). For the UK Government, bringing in funding for this event matters, not only to cover costs and to reduce taxpayer investment but also to defray the expected £250m policing bill to cope with some 150,000 protestors present.

Money must not come before values

The difficulties of the COP26 summit in relation to sponsorship gives us an insight into the issues we grapple with as arts organisations seeking to access sponsorship. Some common themes include:

1. If money is the main driver we have a problem. COP26 has security concerns that need funding, but if we put money ahead of values we will run into difficulties. A key question is whether it should have been possible at all for corporates to use exhibition space to promote their brands to the public at the Glasgow Science Centre.

2. Brand authenticity is key. The moral stance of COP26 and the seeming rush to associate brands with the event has led to organisations such as Unilever, well known to have a problematic track record in the area of polluting plastics, having the opportunity to launch a film about ‘action towards a nature positive, net zero world’ as part of the COP25 schedule. Perceived ‘greenwashing’ will only further heighten tensions.

3. Red lines need to be red lines. Brands like Equinor, BP and Shell reportedly tried very hard to become COP26 partners, but despite pressure, UK Government stuck to its commitment to not accept sponsorship from fossil fuel companies.

4. Brands will rarely be comfortable in a logo mash-up. An article in the Guardian outlined not only the frustrations about the last minute organisation of COP26 but that other sponsors were concerned that rival brands were appearing. The commercial return on investment attached to sponsorship means some exclusivity is to be expected.

Environmental consciousness is on the rise

The complex challenges we face require all citizens to be part of the debate. Yet despite the increasing numbers of artists and arts organisations engaging with environmental issues, the ability to attach corporate sponsorship to this sort of work seems a long way off.

There are some emerging exemplars, for example, Somerset House’s brilliant We Are History exhibition, sponsored by Morgan Stanley, which features art that connects the global climate crisis to complex legacies of colonialism. This is a brilliant example of how the arts can influence people’s opinions and behaviours and shift perceptions.

However, in the funding mix it is perhaps the statutory and trust funders that will help lead the systems changes that we need to ensure radical transformation around the environmental agenda in our day-to-day work.

A need for ‘critical work in the environment space’

We are already seeing shifts, for example Arts Council England putting the environment firmly at the heart of its Let’s Create strategy. Similarly, the American based ArtPlace project, brought together foundations, federal agencies and financial institutions to support artists to help transform infrastructure planning, recycling projects and community resilience in a wonderful joined up and long-term initiative.

The initiative recognised the ability of artists to deliver stories to help people understand their role in changing things as a vital part of community development.

Such systems change take time, and deep-seated adjustments will take time. An accommodating network of funders that help organisations to build confidence and momentum could go a long way toward advancing critical work in the environmental space.

And who knows? Perhaps in time we might find the pathways for arts organisations to achieve effective collaboration in the sponsorship arena as well.

Michelle Wright is CEO of Cause4 and Programme Director of the Arts Fundraising & Philanthropy Programme.

This article is part of a series on the theme Fundraising for the Future, contributed by Arts Fundraising & Philanthropy.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.