'It is not simply that everything is getting more expensive, but that the distance between entry points and top prices is increasing'

Price divergence without the nasty surprises

Robbie Kings, senior consultant at Baker Richards, argues for a pricing strategy that is transparent, intentional, fair and aimed at specific groups.

In December, I’d handwritten 40 Christmas cards that needed posting. They showed a picture of our beagle in an elf outfit sitting in front of our Christmas tree. It took an hour and a pack of turkey-flavoured treats to pull off the photo, but the result was pure magic.

I Googled ‘Royal Mail final posting dates 2025’ and everything came crashing down. The golden window for second-class post had closed. All that was left was the wild west of first class. I’d done it again. But it was fine, surely a first-class stamp only costs around… oh.

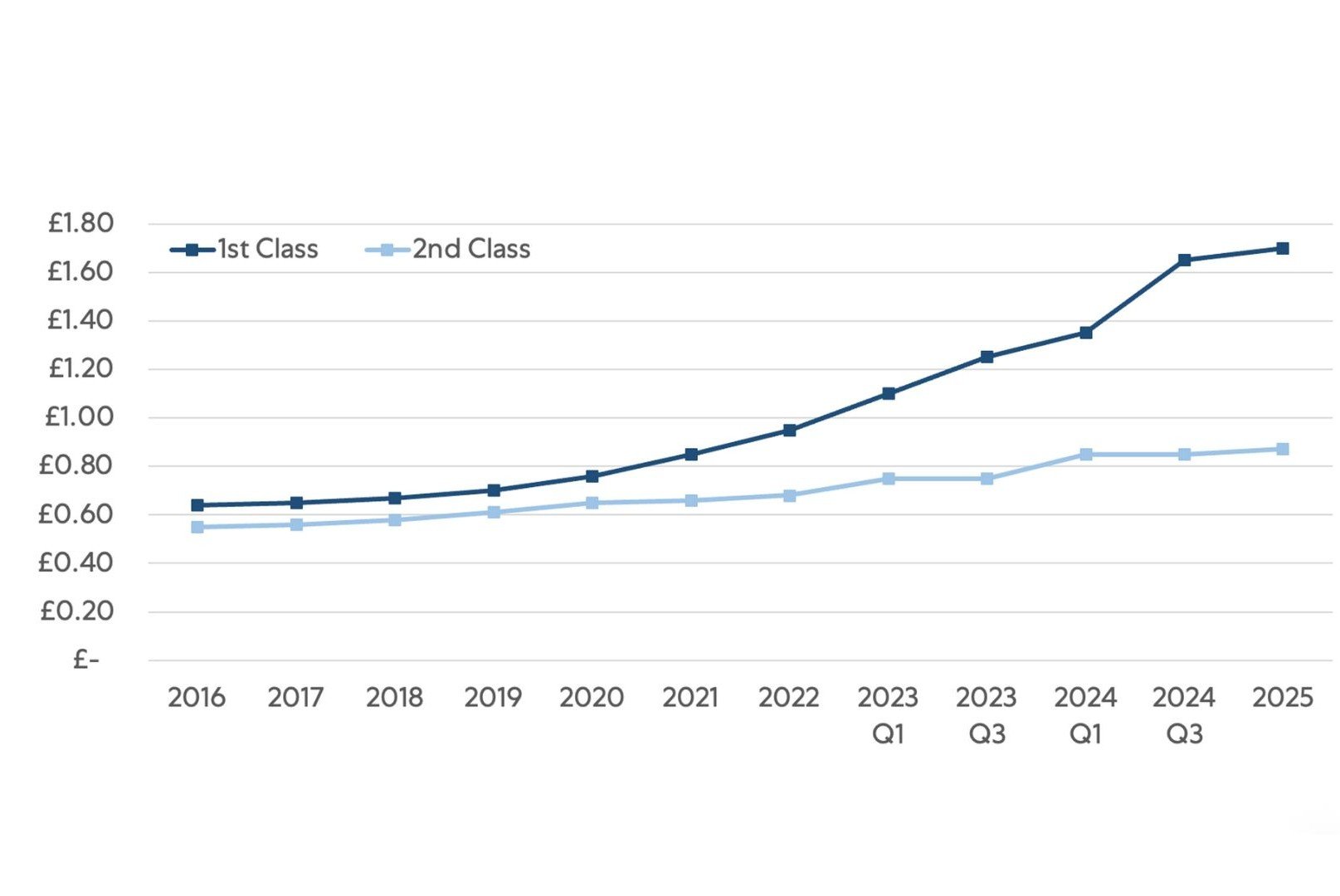

One of the more visible signals of how pricing structures are reshaping buying decisions may be hiding behind a perspex screen at the Post Office. A first-class stamp now costs £1.70 while second class is 87p. In 2022, they were 95p and 68p respectively – the gap since then has widened dramatically. While the price of second-class postage is capped by Ofcom, Royal Mail has more commercial flexibility to raise prices at the top end.

If you work in the arts, this pattern is likely to feel familiar. The same thing is happening to tickets, memberships and experiences across culture. Not uniformly, and not always neatly, but with a clear direction of travel. It is not simply that everything is getting more expensive, but that the distance between entry points and top prices is increasing.

Premium options

Over the last few years, we have seen a widening spread between entry prices and premium options, reflecting a world in which audiences are more cautious about everyday spending but still prepared to pay for something that feels special, comfortable or reliable. This pattern shows up elsewhere too.

Theme parks offer a useful example. Queue skipping, once limited or optional, has become a core revenue strategy since the pandemic. Standard entry still gets you through the gates, but paid fast-track systems have multiplied, become more layered and grown more expensive. At major UK parks, fast-track passes can now cost as much as, or more than, the original ticket. Fancy sleeping in a giant biscuit at Chessington World of Adventures’ OREO-themed room? A night there will set you back £521.

What has changed is not the existence of premium options, but their importance. The basic experience remains, but those willing to pay more can now avoid friction or opt into something indulgent.

Sport has moved in a similar direction. Across top-flight football, clubs know that increasing the cheapest tickets risks backlash, protests and reputational damage. In response, many have limited price rises at the bottom end while expanding premium seating and hospitality-led experiences. The stadium still contains affordable seats but is increasingly supported by higher-yield layers aimed at corporate and higher-spending fans.

Even leisure attractions that once prided themselves on simplicity have shifted. Zoos, aquariums and heritage sites increasingly offer behind-the-scenes tours, animal encounters and early-access upgrades. At West Midlands Safari Park, standard admission is £19.90, while an overnight stay in one of their Safari Lodges costs £1,500 a night.

What does this mean for the arts?

At a time when costs are rising, audiences are selective and there is very little slack in the system, it doesn’t have to be a choice between premium pricing and access. Instead, it’s about holding a range of prices deliberately and carefully.

- Providing deliberate price ranges

First, it means offering a clear range of prices and being open about what that range is doing. Some people will only attend if the entry point is genuinely affordable, while others are prepared to pay more if the experience feels worth it.

A well-designed range allows organisations to align with how people actually behave, and to respond as demand shifts. Algorithms can help with dynamic pricing when demand is unpredictable, but they are only as good as the judgement around them. Used well, they support decision-making; without oversight, they risk widening gaps.

- Being clear about value

Second, it means being clear about value, particularly at the premium end. Higher prices tend to be better received when they are linked to something tangible, whether that is better seats, greater flexibility, priority access, added comfort or a social experience that feels worth the cost.

In tougher times, audiences are less forgiving of vague promises. If premium pricing is doing more of the financial work, it needs to feel grounded in something real.

- Designing access intentionally

Third, it means designing intentional concessions rather than relying on sprawling or poorly explained discounting. Broad concessions often benefit those who are already well served and confuse everyone else.

Intentional concessions are different. They are clearly defined, aimed at specific groups an organisation is prioritising, and are easy to find and understand.

None of this is straightforward

Designing a price range takes time, confidence and clarity about who an organisation is for. But the alternative is to allow pricing to drift under pressure, until the gap widens without anyone quite owning it.

Rising costs, tighter budgets and more cautious spending are part of everyday conversation. What audiences find harder to accept is inconsistency: premium prices without a clear explanation, or access routes that exist on paper but not in practice.

Organisations that navigate this moment best are unlikely to be those with the lowest or highest prices. They will be the ones that make their pricing easy to understand, and that can explain openly why different prices exist, what they are for and how they fit together.

Price divergence is not a failure of values. It is a response to uneven demand in a challenging economy, where people are making fewer choices, more deliberately. Handled well, it can be one of the few tools left that allows organisations to remain financially resilient while keeping their doors open to as many people as possible.

Not cheap tickets for everyone, all the time, but a fair route in, a clear reason for the premium, and no nasty surprises at checkout.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.