Pulse report: Sexual harassment in the arts – is enough being done?

Following revelations of inappropriate behaviour by high-profile individuals in the arts, an ArtsProfessional survey has revealed the experiences and views of the sector’s workforce. Frances Richens reports on the findings.

Revelations about abuses of power by high-profile individuals working in arts, culture and entertainment have triggered a watershed moment in relation to workplace sexual harassment.

Allegations of inappropriate behaviour are now surfacing on a weekly basis, leading to questions about the particular vulnerabilities of cultural workplaces, and whether arts organisations are doing enough to create safe working environments.

This research by ArtsProfessional has attempted to uncover the extent of the issues around sexual harassment in the arts and how the sector is responding to them.

An online survey ran between 25 October and 15 November 2017. It was distributed to readers of ArtsProfessional and received 1,580 responses (of which 861 were complete), predominantly from those currently working in or with an arts or cultural organisations in the UK. It asked respondents about their experiences of sexual harassment, their employer’s approach to dealing with it and their views on why inappropriate behaviour may go unchallenged.

Read the full survey responses in the pdf document here, including more than 1,200 comments related to sexual harassment in the arts. (Please note, the figures in this pdf won’t always match those in this report, as these have been adjusted to take into account the logic of the survey.)

The extent of sexual harassment in the arts

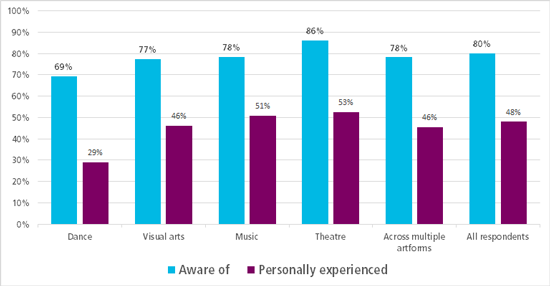

Proportion of respondents that are aware of and have personally experienced sexual harassment, by artform they work in |

|

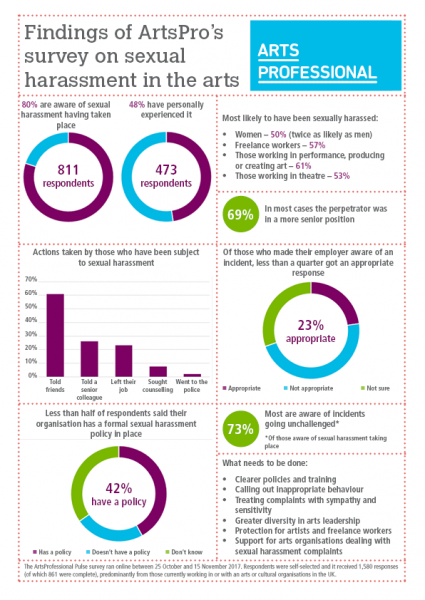

80% of respondents to the survey were aware of sexual harassment having taken place in arts and cultural workplaces. 473 respondents – 48% of all those who completed this section of the survey – indicated that they had personally been subjected to sexual harassment.

While the survey was self-selecting and is not representative of the workforce as a whole (83% of respondents were female) the results do suggest the issue is endemic in the sector.

Several factors are related to the likelihood of a respondent having been sexually harassed:

- Being female

- Working in a freelance position

- Working predominantly in performance, producing or creating art

- Working in theatre.

In 69% of cases the perpetrator was more senior than the respondent; 9% were at the same level and in 6% of cases the perpetrator was a board member.

Other incidents of sexual harassment involved people external to the organisation, including donors; audience members or participants; journalists; external suppliers or consultants; funding body workers; professional acquaintances or people met in an advisory context; and friends of co-workers. There were several reports of incidents in higher education settings and inappropriate behaviour by teachers.

Asked about the specific contexts in which incidents took place, almost a third knew of sexual harassment occurring in office environments. Many reported incidents occurring at networking or training events, and in settings where the lines between social and professional blur, such as drinks receptions, after-show parties or on tours.

Around a quarter knew of sexual harassment occurring between peers in artistic environments, but this figure rose to over half amongst respondents that said they worked in performing/producing/creating art. Some reported high-profile figures abusing their ability to ‘make or break’ someone else’s career, and rehearsal room practices were raised as an area of particular concern by many.

| “The writer, or director or leading performer can exert authority and wield power at certain points in the process that is then covered by the generally accepted rule that it is all about making the ‘best’ show.” |

What happens when sexual harassment occurs

Of those that said they were aware of sexual harassment taking place in arts and cultural workplaces, almost three quarters (73%) said they knew of incidents that had gone unchallenged.

This is reflected in the experiences of those that reported being personally subjected to sexual harassment: Of these only 26% told a more senior member of staff and 8% raised a formal complaint. Almost half (48%) didn’t tell anyone they worked with.

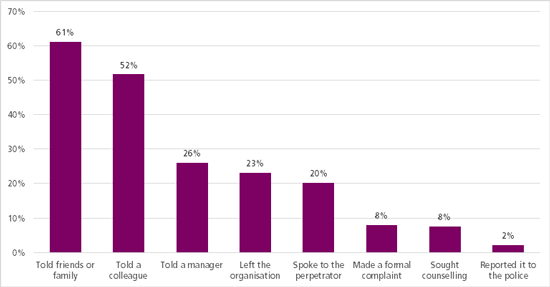

Actions taken by those who have been subjected to sexual harassment |

|

The most common action taken after being sexually harassed was telling friends or family members: 61% did this. Half said they attempted to avoid the perpetrator; while a fifth spoke directly to them – an approach that was more common among freelance workers (30% did so).

Of those that did report the incident to their employer, 41% said their employer took no action following their report (baring offering advice). Only 23% were happy with the response they received from their employer (47% said the response wasn’t appropriate and 30% weren’t sure).

| “I have been made to feel as though my complaint has not been taken seriously. I’ve been offered no support and despite raising the issue a year ago, there has been no follow up or offer of further discussion since.” |

Almost a quarter of respondents that had been sexually harassed (23%) said they left the organisation for reasons connected to the incident. Around 8% took time off work and/or sought counselling.

Asked about any actions their employer took following their complaint, only 11% were aware an investigation had been carried out, and just 1.5% said their employer implemented a sexual harassment policy.

The most common response from an employer was to limit professional contact between the complainant and alleged perpetrator: 15% did this. In 3% of cases mediation or counselling was offered, and 2% of employers referred the case to the police. 1.5% of cases reached an employment tribunal.

Some respondents reported that the perpetrator was dismissed by their employer, or not hired again if they were freelance. Some said their employers reported the incident to a funding body.

Many commented about the negative experiences they had telling their employer about sexual harassment. Some were not taken seriously, not believed or even reprimanded for raising a complaint.

| “I told senior staff I could not work with an individual who had assaulted me in the past, and they refused to believe me and actively accused me of lying.” |

Many felt the actions their employer took in response were inadequate, or criticised them for not keeping them informed of their actions or breaking a promise of anonymity. Some felt they were treated with a lack of sensitivity or that the organisation put the perpetrator’s needs and feelings above their own.

Why sexual harassment goes unreported or unchallenged

While some respondents who had been subjected to sexual harassment said they chose not to take a complaint forward, or that they felt the situation didn’t warrant it, many commented on a working culture that fosters a fear of speaking out, and a lack of confidence that employers will deal with situations sensitivity and professionally.

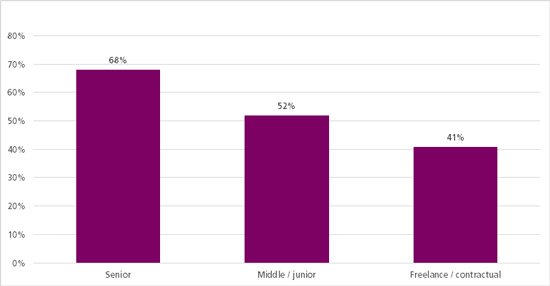

57% of employed respondents believe their organisation would deal with a complaint of sexual harassment appropriately (18% said it wouldn’t and 25% are not sure), but this figure is highest amongst senior workers and falls among lower level staff and freelance workers.

| “I asked my line manager to not contact the artistic contractor who had conducted the assault, I did this because I knew my line manager would deal with it inappropriately and likely joke about it with the artistic contractor, furthering my embarrassment.” |

Proportion who are confident the organisation they work for/with would deal with an allegation of sexual harassment appropriately |

|

Only 42% of respondents who work for or with an arts organisation know that their organisation has a formal sexual harassment policy in place (23% report that it doesn’t and 35% don’t know). 55% of freelances don’t know if the organisation they are currently working with has a policy.

The proportion confident that their employer would deal with a complaint appropriately rises to 72% among those whose organisations have a formal policy in place; but falls to 46% among those that said it doesn’t or that they don’t know.

| “Structuring an industry around freelance workers systematically disempowers people from speaking out; there is a lack of clarity when you are a freelancer about what each company’s policy is, and a fear for future job prospects.” |

Unreported

A lack of awareness of, or confidence in, reporting systems was one of the main reasons respondents thought someone who was subjected to sexual harassment may not come forward. Particular issues were highlighted in small organisations without HR capacity, or when the perpetrator was the most senior staff member, and there isn’t an obvious person to raise a complaint with.

| “When the person who would ultimately be responsible for implementing the policy is the one violating it, it doesn’t fill you with confidence that your concerns will be taken seriously.” |

Some thought not knowing what constitutes harassment may also leave someone unsure if they should raise a complaint.

Some of those with personal experiences said shock, or not realising until later on what had happened, played a part in them not reporting an incident. A feeling – however irrational – of being complicit, or a fear of being seen to be, was also a barrier.

| “So many victims, including myself, freeze in the situation. Then, afterwards, we either don’t know what to do, how to do it, or are too scared or distracted to do the right thing.” |

Many highlighted the importance of working relationships in the arts and said this could prevent people from speaking out, as being seen as ‘a trouble-maker’ may limit their future work opportunities. This is a particular problem for artists/performers and freelance workers, who may also see making a complaint as not ‘worth it’ if they’re only on a short-term contract.

Some said they wouldn’t want to ‘ruin’ a project or production, or bring negative attention to their organisation, by complaining about a team member.

| “I have never said anything and never will publicly because unfortunately I desperately need these directors support in order to progress in my career.” |

Unchallenged

There are many reasons why an arts organisation may fail to act when sexual harassment is reported, or why a room full of people who witness an incident may stay silent.

| “When arts organisations have spent years promoting an artist’s work they especially don’t want to hold them accountable – it’s more than them being an ultimately replaceable employee, they rely on the artist’s reputation to form the basis of their own work, so they are very protective of that.” |

When the perpetrator is in a position of power – which the results show is often the case – this can lead to the impression they are too important to criticise. Around half of respondents had known of an incident of sexual harassment going unchallenged because of a person’s seniority or artistic reputation.

The willingness of arts organisations to act on complaints was seen as compromised when the perpetrator was critical to its artistic reputation or financial success. This was highlighted in cases involving senior managers, but also ‘star’ artists and important donors.

| “Any allegations would be taken incredibly seriously if regarding a low-level staffer but would be completely ignored if they regard a patron, and potentially threaten your job if they involved a high-level donor. I’ve seen all three happen.” |

Some had witnessed the ‘artistic temperament’ being used to excuse inappropriate behaviour. Many had heard incidents dismissed with a ‘that’s just their way’ attitude, or said the ‘touchy feely’ environment of the arts made it harder to challenge sexual harassment.

| “Close, sometimes affectionate, working relationships, alongside a culture of work-related socialising, can blur the edges between appropriate and inappropriate behaviour” |

A lack of capacity to deal with sexual harassment claims, particularly in small organisations, was raised by many. Some commented that arts organisations are already ‘stretched too thin’ and that they didn’t have the specialist knowledge and skills to deal with these incidents.

Many were critical of the failure of boards to deal with complaints of sexual harassment. Some said they weren’t engaged enough in the organisation and preferred to let situations ‘blow over’. Others said that the profile of the board – tending to be male-dominated and older in age – meant they were less likely to take claims seriously; or that they tended to value and believe senior workers over more junior ones.

| “I am the person who would be responsible for dealing with it and I don’t feel I have enough experience or training – as with many arts organisations we have a tiny pool of staff and little funds so we have to take on roles we are not precisely trained for.” |

Many also pointed to wider cultural problems, such as sexist attitudes, and highlighted the fact that the arts workforce is predominantly female, but that the highest levels of management are still dominated by men.

What needs to be done

While many respondents thought that the issues around sexual harassment in the arts were no different to – or any worse than – other industries, the results of this survey have highlighted particular aspects of cultural workplaces that make them vulnerable to abuses of power.

These include the fact that work is highly competitive: a good reputation and the right contacts can make or break a career, while successful individuals tend to be placed on a pedestal, which can make abuses of power harder to challenge.

There also tends to be a blurring of boundaries between the professional and the social in arts workplaces. Particular issues were highlighted around freelance workers and artists, including the intensity of the rehearsal room and arts education settings.

Responses indicated what arts workers, employers and industry bodies should do to challenge the issues around sexual harassment in the arts:

- Through policies and training, arts organisations need to make it clearer to all staff – including freelance workers – where the line lies between appropriate and inappropriate behaviour, and what they should do if they witness or are subjected to sexual harassment.

- It is everyone’s responsibility to call out inappropriate behaviour and insinuation, and to challenge the excuses made.

- Arts organisations must follow their own policies and take all complaints seriously. More engagement from boards is needed on the issue.

- All complaints should be met with sympathy and sensitivity, and organisations must balance transparency with confidentiality.

- The arts need greater diversity in leadership.

- Changes to audition, rehearsal room and tour procedures are needed, along with better protection for freelance artists from industry bodies and unions.

- More support is required for small organisations that don’t have HR capacity.

- Funders and industry bodies need to be sympathetic and possibly provide support for loss of income if someone has to be dismissed – no organisation should sweep an issue under the carpet for fear of monetary loss.

- More research is needed into sexual harassment and inappropriate behaviour in educational settings.

Download AP Pulse: Sexual harrassment in the arts full report (.pdf)

Download AP Pulse: Sexual harrassment in the arts overview (.pdf)

Frances Richens is Editor of ArtsProfessional.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.