Wellbeing behind bars

Dr Alan Clarke shares what he has learnt from a career running arts projects in prisons across Europe

Recently, as part of a European offender learning project, I performed a drama piece in a prison school in Greece. The Insider reflected the plight of prisoners through international literature. The performance took place before an audience of around 30 inmates and European delegates, squeezed into a converted cell. It went down really well despite few of the prisoners understanding English. At one point, following an extract from Brecht’s Little Mahagonny showing the terror of someone awaiting trial, the prisoners broke into spontaneous applause. It had clearly touched a raw nerve, and discussions afterwards confirmed that they had empathised completely with the situation I had presented. They also told me how much they needed such input – it had been two years since their last drama activity. This experience reflects not only the impact which the arts can make on those behind bars but also their need for continual creative stimuli.

My introduction to prison art was six years earlier, attending drama workshops and performances in Brixton Prison organised by Bruce Wall of The London Shakespeare Workout. Although I had worked for many years with deprived young people as a drama teacher in further education, I was totally unprepared for this experience. What struck me most was how important it was for the inmates, particularly when presenting their work to a wider public. There was an intensity, directness and honesty about their acting which I have rarely come across in other contexts

Following this I built on my previous experience of running European projects by organising a number of prison arts initiatives, firstly for The Manchester College, currently for The College of Teachers. I have witnessed some incredible events: music concerts in Italian, Greek and Northern Irish prisons; an exhibition of offender art in a disused jail in Denmark; hip-hop dancing in Oslo Prison; an animation workshop in Vilnius high security prison; readings by international authors in German prisons; and drama sessions and performances across Europe and beyond. And my first impressions of the positive impact of prison arts have been constantly reinforced.

Such projects provide opportunities not only to share good practice but also to analyse its effects. For the Art & Culture in Prison project I was involved in a survey of cultural activity in prisons across four European countries. The overall impression was of the surprising quantity and range of arts events, provided both internally and externally in all art-forms, as well of the great demand for more of such activities.

But why are the arts so important in a prison context? Much funding, both at national and European level, is focused on the educational benefits. Given that the overall prisoner profile is of people with low self-esteem, poor literacy and communication skills, who have rejected or been rejected by formal schooling, often turning to drink, drugs or self-harm to distract them, the arts are a proven way of acquiring basic life skills and stimulating educational potential. They also are a great help in motivating inmates to find alternatives to a life of crime when they are eventually released.

But there are more benefits to arts in prisons than mere functional gains. Even the more comfortable prisons are awful places, particularly when so much time is spent locked up in a cell. Human beings need positive impulses to confirm their identities and an active feeling of wellbeing. Without this, especially deprived of regular contact with family, friends and children, prisoners have huge problems coping, as proven by frequent suicide attempts.

The arts can play a major role in overcoming this, both by providing opportunities for prisoners to share their thoughts, experiences and creations with others, and to give them something positive to occupy their minds. Making up stories or poems, creating pictures or music, working on characters for a forthcoming drama production, in some prisons even editing videos or sound recordings; all of these activities can help in the humanising process so necessary for wellbeing in our prisons.

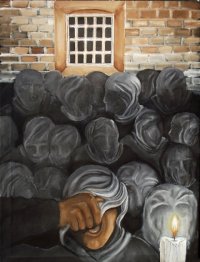

At a recent exhibition of prison art, I was struck by a painting by long-term prisoner Clive Ellis. It shows a group of people, faces completely hooded, in a cell lit only by a candle, one of them trying desperately to lift his hood. It is titled: I am not a number. Art can help prisoners become human again.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.