Healthy prospects

Amidst public funding cuts and the turmoil of health reform, Tim Joss sees a big future for arts in health

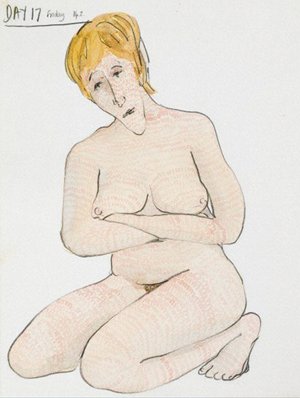

Health and the arts in this country is a story of flawed passion. Players in this story are fierce in their belief that the arts can improve health and well-being. For decades, artists have shown that the arts can humanise the antiseptic, medicalised world of health services and help us humans make sense of it. Just look at Barbara Hepworth’s tender drawings of work in operating theatres: gentle hands and attentive eyes concentrated on the patient. Look at Bobby Baker’s Diary Drawings, exhibited at the Wellcome Collection in 2009 and now published.

But … I can give you many buts, and here are three. I am thinking of a surgeon professor at Great Ormond Street Hospital: passionate, yes, but too busy to connect the arts and health worlds in ways that humanise the everyday work of a GP, health visitor or hospital doctor. Not surprising then that the public applauds the work but regards it as low priority ‘fluff’. I am thinking of the many NHS Trusts which stop short of using NHS money for the arts. Typical is the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust: “All our projects are funded by grants … no money is taken from healthcare budgets.” Arts on prescription schemes are expanding but, while pharmaceutical companies are paid for medical prescriptions, artists and arts organisations are not. This condemns projects to grant-dependency and stifles growth.

The Sidney de Haan Research Centre for Arts and Health has a £250,000 National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) grant for a rigorous study of the benefits of singing for the over-60s. This is a brilliant advance but generally the NIHR hesitates over arts activities, designating them “complex interventions”. It is used to the testing of drugs. A pill is the same every time and it targets specific functions of the body. An arts activity is never the same and it is for the whole person – and that is what gives it its power.

Enough of the buts. I believe this story has reached a breakthrough. Sixty-five years of public investment have given the UK one of the strongest banks of ‘cultural capital’ in the world. Deploying that cultural capital in dedicated arts spaces is a job half done. Connecting artists more with places where people spend their daily lives is the job’s crucial other half: at work, in school, in prison and in health settings. Here the arts can be more than a nice extra: vital to well-being, and to personal and community development.

For the arts to be considered a viable option in health, a substantial evidence base is needed. Research is patchy and dissemination of results poor, but a fresh push has begun. An arts in health research network has just been launched and there is movement on accepting complex interventions as more than the sum of their parts. Health economics has been particularly weak but the health economics team at the London School of Economics is now involved in all the Public Engagement Foundation’s arts in health projects. And, to give one local example, a GP working with the University of Gloucestershire has run a three-year artist in residence scheme to study the impact of artists on GP consultation rates and overall NHS spending on GP patients.

As research progresses, a shift becomes possible from grant-dependency to earned income – for services attuned to the NHS’s needs and fees large enough to cover the arts organisations’ costs. The Reader Organisation is one of the leaders. It “renews the now lost sense of literature as a life-enhancing creative power”. It brings groups together to share and discuss literature – from the accessible to Dante and Milton. It has fee income from several NHS trusts including Merseyside’s large mental health trust.

The Public Engagement Foundation also aims to build on evidence. Here’s an example: if you need an operation and choose recorded music to listen to before and afterwards, then you will need fewer painkillers and leave hospital earlier. The LSE health economics team can put financial value on these two things and so we have the prospect of a music service saving the NHS money. Think of the £10bn plus annual NHS drugs bill and the cost of a hospital bed. Even small inroads into these budgets offer a big market for the arts.

So building blocks are being put in place. Research is getting stronger. Arts organisations are developing ‘demand-side’ thinking: understanding what the NHS wants and how it buys services. More blocks are required. We need training for both sides: arts organisations to understand the health world; and the health world to understand what is on offer and influence what is developed. We need mutual support and shared learning amongst those involved in arts in health. And, when the latest NHS upheaval is over, we will need better engagement from the Department of Health and better links between that department and DCMS. But we are on our way.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.