Photo: Sophie Baker

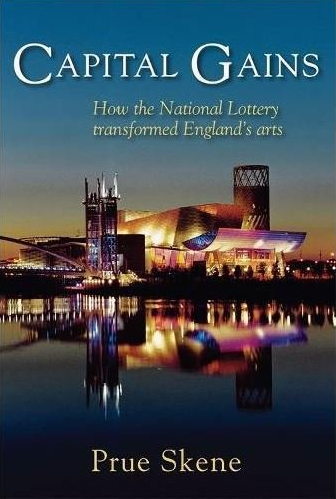

Book review: Capital Gains

David Powell reviews Prue Skene’s candid account of her tenure as Chair of Arts Council England’s Lottery panel.

Capital Gains is the story of how not to spend a billion pounds. Prue Skene has written an account of her tenure as a member and then as Chair of Arts Council England’s (ACE) Lottery panel. This covered the first seven years (1994 to 2000) of ACE’s life as one of the National Lottery distributors.

Based on Skene’s diaries and some contemporaneous data, Capital Gains also includes some personal reflections on Skene’s life in the arts before and after her Lottery labours, and briefly offers some opinions on the state of the cultural nation. There are, in addition, six short interludes where she connects her narrative to Lottery-supported capital projects from the period.

There are a number of moments in the book when Skene’s dismay, frustration and anger are clear to see

Several themes run through this book, which many readers will recognise. One constant theme is the absence of a national strategy for the distribution of the Lottery millions to the arts sector. Such a plan (discouraged, if not forbidden, by Government at the outset) should have embraced strategic thinking across each of the English regions. It might then have identified the place of the largest national and regional projects in relation to audiences, communities and the broadest demographics, enabling a more effective, equitable and transformative use of the money spent by those buying Lottery tickets.

Of course, this could only have happened in another more progressive parallel universe (the one in which the Heritage Lottery Fund operated – a much more equitable and effective distributor, despite being subject to the same policy constraints). And it did in exceptional places like the north of England (“where one could draw on a blank sheet of paper…”). There, despite such dismissive metropolitan views, its collegiate and transformative 1995 ‘Case for Capital’ built on a decade or more of preparation, planning and close collaboration between Northern Arts, arts companies and local government.

What we got instead was an under-regulated goldrush. This was exacerbated by ACE’s inability to manage the uncertainties of its incoming cashflow from the hundreds of millions of ‘good causes’ income with the persistent and growing applications in the pipeline. In the absence of any plan, there were processes, procedures and projects aplenty. Skene is an invaluable, if partisan, witness to this, as well as being an influential participant.

A second theme is the dominant place in the Lottery agenda of London and the biggest projects, particularly those with the greatest sense of entitlement. Neither the Southbank Centre nor the Royal Opera House – to pick the two most egregious examples – come out well in this.

London has always been the main object in ACE’s eye, from the Arts Council of Great Britain’s earliest days, with its priority to rebuild London’s arts in the post-war years, through to the past 20 or so years of Lottery spending. Capital gains indeed.

There are a number of moments in the book when Skene’s dismay, frustration and anger are clear to see. She writes, nearly 20 years after the events, about the breath-taking irregularity and arrogance of Mary Allen’s move from leading ACE as Secretary General to becoming Chief Executive of the Royal Opera House in 1999.

Skene is constantly exasperated at the failure of ACE’s council and senior management to provide leadership, direction and strategic guidance for the Lottery. She is particularly disappointed at the inability of the ‘new team’ of Gerry Robinson (Chair 2000-05) and Peter Hewitt (Chief Executive 2000-08), who promised and then failed to deliver effective leadership and direction when long-term planning was urgently needed – both for the purpose of the Lottery and its financial management.

Capital Gains is less about ‘How the National Lottery transformed England’s arts’ (the subtitle) and more about how the onus of distribution had a negative impact on ACE itself in the formative years of the arts Lottery. It provides a relatively candid view of the key players in ACE, Government and the wider arts community. There are more photos of ACE members and senior management than of Lottery-funded projects, which reflects the weighting given in her account to great and not-so-great men and women in what is patently a tale of ACE’s increasing unfitness for purpose as a Lottery distributor.

Skene closes by saying that the book probably won’t teach many lessons. It clearly does, although whether Government and ACE, or even its co-dependent cohort of national portfolio organisations, will recognise what the lessons are, let alone be minded to take note, is quite another matter.

David Powell is co-founder of GPS Culture. He was the author of Case for Capital, and has been a Lottery consultant, applicant, project leader, assessor, commentator and a regional arts board member. He can be seen (most easily with a magnifying glass) on the roof of the Baltic Flour Mill (photo viii opposite page 65 of Capital Gains).

www.gpsculture.co.uk

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.