As budgets tighten, many local authorities feel they have little choice but to cut spending on arts and culture. But how is the sector reacting and what should be done to help mitigate the damage? Frances Richens shares the findings of ArtsProfessional’s latest Pulse survey.

The amount of money central government directs to local authorities across England has fallen by 38% since 2010. Cuts, efficiencies, and renewed efforts to generate income are priorities in councils across the country.

The arts – which don’t benefit from statutory status – have gained an unfortunate reputation as being an easy cut for councils facing ‘difficult decisions’. A 2016 report by Arts Council England estimated that, since 2010, local authority investment in arts and culture had declined by £236m – equivalent to 17% – and warned that cuts were likely to continue.

As the biggest funder of arts and culture across the country, local authorities’ decisions are having a significant impact on arts organisations and local arts infrastructures. In some places, local authority support for arts and culture has stopped completely.

This piece of research from ArtsProfessional has attempted to shed light on the effects of these spending cuts, but also to generate a better understanding of how arts organisations are coping and identify some potential routes forward for the sector.

An online survey ran between July and August 2017. It was distributed to readers of ArtsProfessional and received 506 responses, predominantly from those working in or with the arts and culture sector, some within local authorities. It asked respondents for their observations about how local authority support for the arts had changed, how arts organisations were responding and what should be done to steer the sector towards a thriving future.

Read the full survey responses in the pdf document here, including more than 600 comments related to local authority support for the arts.

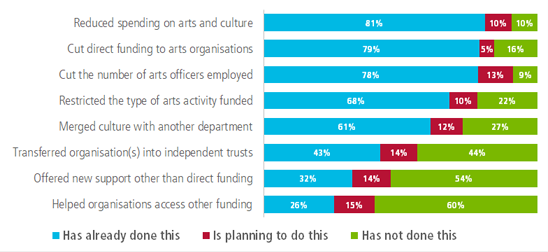

How local authorities have reacted to cuts

How is your local authority responding to cuts?

|

|

Just one in ten respondents reported that their local authority has made no cuts to spending on arts and culture in recent years. Of the rest, 81% said their local authority has already made cuts while the remainder said it is planning to do so.

These cuts have resulted in closures and reduced opening hours for council-run arts venues, reduced council-led arts services and increased charges for services. One said the price of art classes has risen to such a degree that they are now “pretty much art-classes for retired millionaires only”. Others reported severe increases in fees for – or the complete closure of – spaces that can be hired by arts organisations and community groups.

Almost 80% said their local authority has cut the number of arts officers it employs. Others reported over-stretched staff, reduced wages, an increasing reliance on freelance staff and a cut-back in training offered to local authority staff.

Cuts to services and staff numbers have also led to reports of local authorities offering less non-monetary support for arts organisations.

Although up to a third of respondents were unaware of their local authority’s response to funding cuts, of those who were, almost three-quarters said their local authority has or is planning to merge culture with the functions of another department. Over half have or are planning to transfer council-run arts organisations into an independent trust. Some described how their local authority is offering tenders for arts-related activity.

“We are aware particularly of the unintended consequences of cuts to local authorities: e.g. increased rents for community groups to book village halls and other venues for activities; closure of performing arts/music libraries in public libraries; VAT suddenly charged on room hire by local authorities (irrecoverable for small grassroots groups); closure of spaces which can be hired affordably by community groups for activities and events, etc.”

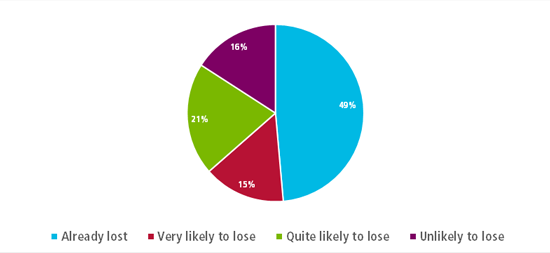

Cutting arts grants

Do you think your organisation will lose local authority funding?

|

|

Some of these spending cuts have also resulted in direct funding reductions to artists or arts organisations: 78% said their local authority has cut direct funding and a further 13% said it is planning to do so.

Of the respondents who work for arts and cultural organisations, just under 50% said they have lost some funding from their local authority, with a further 36% predicting that they are likely to lose funding in the future.

Some said that cuts are happening without warning or consultation and reported a lack of support for those experiencing cuts.

“Buildings and organisations are closing as a result of these funding cuts. I believe this is due to the lack of time to prepare, due to last minute budget forecasting and changing.”

Good news? It’s a postcode lottery

“Local Authority cuts are not nationwide. Some areas are increasing support for cultural activity.”

However, not all comments were negative or pessimistic. Some reported that their local authority is maintaining a commitment to the arts or finding innovative ways to support the sector while cutting spending. Amongst those singled out for praise were Hull, Manchester, Leeds and Islington.

Particular praise was given to local authorities that had worked closely with the sector to mitigate the damage of spending cuts, in particular by collaboratively reviewing delivery models or using funds more strategically. One respondent described how their local authority had undertaken research, including mapping activities.

“[The local authority has] taken a strategic approach by researching and mapping activity, analysing the environments within which it works, being more outcomes focused and developing new partnerships and collaborations.”

Less than a third said their local authority had offered new types of support, other than direct funding, but several left comments about this type of activity, which includes promoting collaborations and cross-partner funding bids; advocating for the arts; and enabling resource sharing.

Cause for concern

Respondents raised a number of concerns about the way local authorities are handling cuts to arts and culture. Several worried that councils are protecting their own venues, services and jobs at the expense of the wider sector. One said that, in their area, council-run venues “got the smallest cuts”. Another said: “Some local authorities are penalising arts organisations with cuts in order to keep their own direct delivery services and staff team going.”

Many raised concerns about a lack of a clear strategy for arts and culture in their local authority, or the “constant reconfiguration of priorities”.

“It all seems very disjointed and a lack of long-term strategic thinking and planning.”

Some connected this to the loss of arts officer roles. One said “officers have retreated into administrative and bureaucratic roles and designated responsibility for decisions to others”. Others highlighted the “loss of expertise and knowledge” in relation to art and culture that local authorities are suffering as a result of these posts being cut.

Some said their local authorities are becoming more financially driven and less likely to take risks, and that this is resulting in them working increasingly with commercial arts organisations, or only funding organisations they have existing relationships with.

In some areas, respondents said local authorities have started competing with arts organisations for other forms of funding. One noted that their local authority has become one of Arts Council England’s National Portfolio Organisations, “therefore taking more funding away from the arts sector they have previously funded and developed”.

Another said: “[The local authority] has become a competitor, seeing strategic funding as an opportunity to sustain itself, and articulating a model of ‘culture-led regeneration’ that aims to draw in funding to the LA.”

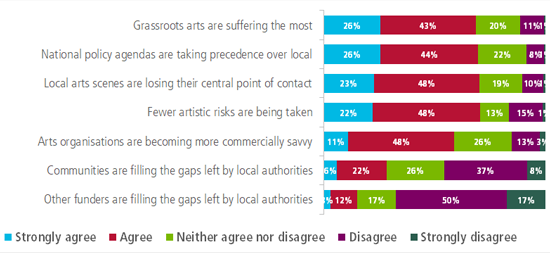

What is happening in the arts sector as a result?

What effect are the cuts having on the wider sector

|

|

Increased competition for funding

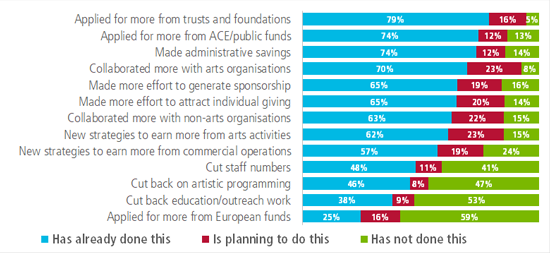

As a result of local authority cuts, the vast majority of arts organisations are applying for more funding elsewhere. 95% said they have or are planning to apply for more from trusts and foundations, and nearly as many are planning to apply for more from their arts council or other public funds.

However, some who had tried these routes noted that their applications hadn’t been successful, and the majority (67%) don’t believe that other funders are filling the gaps left by local authorities.

Some raised concerns about the pressure this is putting on these funding streams, particularly with returns from the National Lottery in decline. 70% thought that national policy agendas are taking precedence over local priorities, and some were worried that this is causing an over-reliance on project funding that does not support sustainability.

“Where LA funding is cut and the proportion of Arts Council funding increases, there is a danger that arts organisations are more motivated to pursue a national agenda rather than one that is informed by local needs.”

A few also raised concerns that a local authority funding cut often leads to diminished support from other funders, as it suggests “that organisation isn’t worthy of support”.

65% of those who work for organisations facing local authority cuts have attempted to raise more funds by generating sponsorship or attracting more individual giving, with many more planning to do so in the future.

Over half (58%) thought arts organisations are “becoming more commercially savvy”. 62% said their organisation has introduced strategies to make more money from its arts activities, and a further 57% are working to make more through commercial operations.

Around half have cut back on artistic programming in response to cuts. Some linked this to fewer artistic risks being taken: 70% agreed this was the case.

“Safe investments are favoured over new work” said one, while another commented that this is leading to the arts offer becoming “more homogenised” with the same work being programmed at more venues, and organisations being less willing or able to create expensive or artistically risky work.

Some warned that the pressure is forcing arts organisations to raise their ticket prices and this, coupled with the drive to programme work that will sell, is leading to a drop in the diversity of arts audiences and participants.

But others were more positive about arts organisations taking a more commercial approach. One said: “Becoming commercial doesn’t have to mean mediocrity and risk-aversion.”

Others thought the diversification of funding for arts organisations is a good thing, with funding being secured from ‘more appropriate’ sources. Some were positive about working in partnership with other organisations to secure funds.

“We have diversified our funding base. Local authority funding will only ever be a ‘top up’ to our funding. We have decided to be ambitious and bold in response to cuts in order to differentiate ourselves from other cultural organisations in the city and to give other funders confidence in our organisation.”

Making savings

How it your organisation responding to local authority cuts?

|

|

Almost three quarters of respondents who work for arts organisation that have experienced, or anticipate, local authority cuts have made administrative savings. Almost half have cut staff numbers with more planning to do so in the future.

Many commented on the effect this is having on a personal level within arts organisations. There were reports of “‘overworked, overstretched” arts workers, as staff numbers have been reduced, but the work load – in particular around attracting funding – has increased. Some organisations are relying more on volunteers.

“Where loss of funding obviously has huge knock-on effects the reduction in staff numbers of FTE hours means that there is also a huge capacity deficit – this means a lack of people with time or training to raise funds to fill the funding gap. Organisations are left ‘fire fighting’ rather than able to diversify/innovate and change their enterprise model.”

With no money for pay rises, a few commenters described what they see as professionals and artists ‘self-subsidising’ the sector by working more for less. Some warned this has led to people in organisations feeling “undervalued” and morale being at “an all-time low”.

“I am concerned for the future consequences of putting on a brave face.”

Cuts to the grassroots

Respondents generally agreed that local authority cuts are hitting grassroots arts the hardest: 69% said this was the case.

Several attributed this to the fact that larger organisations are undertaking – and seeking funding for – work that was once the preserve of smaller arts groups and community organisations. Such organisations are more proficient at applying for funds and tend to be favoured by funders, “despite their often much larger capacity to fundraise and attract sponsorship”.

“Too many local authorities seem to put all their money and resources into professional groups and arts organisations to the detriment of nurturing and supporting the thousands of people who could and should gain benefit from participating as passionate volunteers.”

The recent increases in charges by local authorities for services and space is seen to be hitting community arts groups particularly harshly. One said they’d witnessed a number of voluntary and amateur arts groups close as a result of “excessive” increases.

This is also having a particularly negative effect on artists. Some reported they are “massively subsidising the arts by working for less” or by funding each other’s projects through crowdfunding. Some are leaving the arts and finding work in unrelated areas.

Many reported that there is less support for arts-led activates for young people and other vulnerable groups, such as those with mental health problems. One said: “Reduction in multiple services, including expressive arts, is causing an increase in public mental ill health.”

Of the respondents working for arts organisations that have experienced or anticipate local authority cuts, just under half have, or are planning to, cut back on their education or outreach work. They see this trend as especially damaging given recent developments in education policy, which are leading to the downgrading of arts in schools.

Loss of ‘central point of contact’

According to 71% of respondents, cuts to arts officer posts within local authorities are leading to local arts scenes losing their “central point of contact”.

Arts officers were described by one respondent as providing a “‘middle layer’ of advocacy and support” and many commented on the negative effects of their loss, especially the advice and support they offered arts organisations in relation to event coordination, marketing and fundraising, and creating connections and partnerships.

“The most dangerous thing is the gradual decline of the arts officer as a central point of information and glue.”

Arts officers are also seen as providing a valuable source of knowledge for local authorities and acting as advocates for the sector, thereby protecting funding and driving strategic thinking.

Several said the loss of arts officers was weakening local networks, although others indicated that networks were filling the gap left by the loss of arts officers in their area. One said: “strong networks can be more effective than an inefficient arts officer”.

What should be done

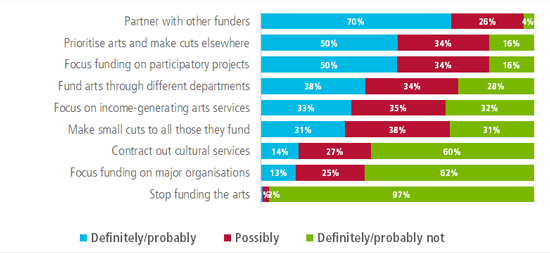

What measures should local authorities adopt?

|

|

Handling cuts and focusing funds

The vast majority of respondents – 97% – were in favour of local authorities continuing to fund the arts in some capacity, with some commenting that even a little support is a “magnet” for other investment. Half thought arts and culture should be prioritised over other areas.

There was less consensus around how cuts – if inevitable – should be applied, and where arts funding should be prioritised. Respondents were evenly split on whether local authorities should “make small cuts to all those they fund”.

One said: “Salami slicing funding is not appropriate in some places: it may be that some organisations can take greater pain than others and some organisations need to be cut in favour of other new organisations.”

Around half thought arts funding should be focused on participatory work, and respondents were generally against the idea of focusing funding on major organisations.

Along these lines, there were many calls for local authority funding to support grassroots arts infrastructure and be used to drive health, social and placemaking agendas. Some felt passionately that funding should be spent locally and on artists or art-making, rather than administration. Others thought small not-for-profits were the most likely to create work that benefited the local community.

“Local authorities should also work more with voluntary arts groups who will provide activity for a lot less money than the, quite frankly, ridiculous sums given for pretty average activity to big arts groups, who seem to spend most of their budget on staffing and other stuff that means diddly squat to the public they’re supposed to be delivering to.”

Despite this, only 38% of respondents said local authorities should definitely or probably fund the arts through different departments, such as social care, and there were many who spoke out against an instrumentalist approach to arts funding.

One said local authorities should aim for arts activity to reach as many people as possible, and “£200k is better spent supporting a larger organisation that reaches 600,000 customers, than a smaller organisation that reaches 20,000”.

Another said: “It is misrepresentation to try and justify arts expenditure from ‘health and wellbeing’. Arts should be able to be seen as vital activities in their own right.”

Several thought there was a place for ‘art for art’s sake’, with one saying that if art is brilliant it “automatically has social relevance”. Another thought it should be supported, but through private funds or by generating revenue.

Several thought a major focus for local authorities should be encouraging arts groups and organisations to become more sustainable and entrepreneurial. To this end, respondents suggested local authorities offer match funding and business development grants, and explore the potential of loans and social investment structures. 70% of respondents thought it was a good idea for local authorities to partner with other funders to make up their own funding shortfall.

“Many of us are innovating… a small amount of support goes a long way. Business support or small grants for business is ideal.”

One respondent raised the concern that arts activities cannot always be self-sustaining: “I think the fiscal argument for culture is a fallacy and things like preschool reading programmes shouldn’t have to generate income to succeed… and frankly government is the only body that can pay for it.”

There was strong consensus against local authorities contracting out cultural services: 60% thought this definitely or probably shouldn’t be done. One commented that this model took money away from artists as “contracted out bodies are also competing for these monies”.

Additional support

Many suggested ways that cash-strapped local authorities could offer non-monetary support to the arts and cultural sector.

Chief amongst these was giving arts organisations access to council resources, including empty buildings. Others suggested offering business development services, legal advice, mentoring and support in strategic planning. Arts officers were seen by many as key to supporting the sector in this way:

“LAs see that deleting arts officer posts saves them £25-30k a year, but that one officer could work to generate much more with a cleverly thought out job description: officer to work proactively to look for, promote and assist in the writing of funding bids, have knowledge of event delivery so that they can supporting/empower community groups to deliver events and activity, work closely with local businesses to find potential sponsorship opportunities and promote how events support the local economy/ tourism economy, etc.”

Some also called on local authorities to help arts organisations financially by waiving licence fees, offering business rates subsidies and relaxing planning laws.

Several called for joined-up thinking across councils to support arts in health and social initiatives, including through cultural commissioning.

Amongst suggestions for innovative ways local authorities could generate new money for the arts were lotteries, introducing tax levies on big businesses or tourists, and forming partnerships with businesses and universities.

Respondents recognised the potential of local authorities to help arts organisations access other sources of funding, however just 17% said this is something their local authority already does.

The importance of openness

However local authorities go about supporting arts and culture, many highlighted the importance of them being open and transparent, and making strategic decisions in collaboration with the sector and the community.

“Local Authorities should consult more with the sector. They are operating in silos which mean their difficult decisions come as a shock, are made through discussions from a narrow view point and often unwisely taken.”

Liaising with arts workers was seen as key to helping local authorities develop an understanding of the sector, and to allowing community needs to inform decision-making. It was also suggested as vital to encouraging community support for the arts.

One said: “Until local authorities admit that they don’t know best and start working together with people on a human level, all they are ever going to focus on is cutting what they’ve always had, instead of offering what is actually needed and valued.”

Some suggested local authorities needed to relinquish their position of leadership. One said they should look for delivery partners in the sector, and move “from a client culture to a collaborative one”.

Several raised concerns about local authorities wasting money, including on badly-run projects and by not monitoring those that they fund closely enough. There were also a few accusations of corruption, and some calls for local authorities to stop spending money on ‘vanity projects’, to reduce the amount councillors can claim in expenses and to cut back their “over-generous pension schemes”.

Recognising cultural value

A key theme to emerge from respondents’ comments was the need for local authorities to recognise and advocate for the value of arts and culture.

Many wrote passionately about the important contribution that the arts make to local economies, community wellbeing and individuals’ health and quality of life.

“Arts and culture generate money for the local economy – they generate jobs, attract people to live and work in a place and contribute to better health and wellbeing. It is counter-intuitive for local authorities to cut funding to arts and culture.”

Many called on councils to work together with other local authorities and arts organisations to lobby central government against cuts. Some thought more needed to be done in terms of research to make the case for cultural value in a way that government would respond to.

One said: “In a world where government only understands the money and the quantitative, the arts needs to offer this kind of evidence.”

Others saw it as central government’s responsibility to encourage local authorities to invest in the arts and to convince them of the benefits they offer to health, education and social care. Several thought arts and culture should be a statutory service.

Education policy was an issue raised by several. Some called for local authorities to perform an instrumental role in supporting strong links between arts and education providers. One commented on the need for them to support the “continued provision of arts into schools/arts education because there is so much research indicating loss of arts departments in schools and general downgrading of arts subjects, and by extension less professional work brought into schools, less extra-curricular arts opportunities and less cultural engagement.”

A collaborative approach

The importance of partnerships was another key theme to emerge from the responses.

70% of respondents who worked for arts organisations that are facing local authority cuts reported collaborating more with other arts organisations. 63% had collaborated more with non-arts organisations, with a further 22% planning to do so in the future, and respondents were generally very positive about this approach.

Many commented that local authorities are in a position to link arts organisations with other council departments and public bodies that may commission arts activities. They are also seen as having a role in encouraging collaboration and coordinating partnerships between arts organisations, and linking arts organisations with businesses and developers that may support or sponsor their work. This role was seen as imperative to driving financial sustainability, as well as reducing duplication and maximising impact across the sector.

“Local authorities and all publicly subsidised or funded arts organisations could and should work harder with local and regional businesses and the private sector in general to identify partnership and sponsorship opportunities.”

Some, however, thought local authorities didn’t necessarily need to lead in these areas of work. One said: “The reliance on LA needs to shift and the sector needs to start doing it for themselves, this is where sector-led partnerships become really important. Partnership can set priorities, secure consortium funding and continue to make the case for arts investments.”

Conclusion

Responses to this survey paint a bleak picture of the effect that government cuts are having on local arts and culture infrastructures. While it is hard to lay all the blame for the concerns raised by respondents at the feet of local authorities – they are only responsible for part of the funding ecosystem – it is undeniable that this drop in funding and support is having a significant impact on the way arts organisations operate.

As a result of cuts – and the demands of funders – arts organisations are having to direct increasing resources to income generation, both through commercial operations and fundraising, while simultaneously attempting to make administrative and staff savings. The comments indicate that it is smaller arts organisations and the artists and practitioners leading socially engaged arts activity ‘on the ground’ – those that rely on project and freelance work – that are suffering the most.

Reports of overworked and stressed staff, along with a reduced capacity in the sector to provide activities for young and vulnerable people, and to work to diversify arts audiences, are particularly worrying.

What is clear from responses, however, is that – even if direct funding is not possible – arts organisations see a very clear and important role for local authorities in supporting the sector and the creativity of communities.

Arts councils operate at a regional level, and only local authorities are in a position to represent and respond to truly local needs. They are also in a unique position to form connections between the arts and local businesses and other public services. There are repeated calls from respondents for this to be their focus. But, whatever they do, local authorities need to think about how their support fits into the national system of arts funding.

Where there is ‘bad mouthing’ of local authorities by some respondents, this seems to stem from them making decisions behind closed doors or without the input of the arts sector. The responses highlight that transparency and forming strategies in collaboration with those affected will always be the best approach.

A close connection between local authorities, local arts organisations and groups, and artists would also give local authority workers an understanding of the value of arts and culture and how their local arts sector operates – which is becoming increasingly important (but also increasingly challenging) as arts officer posts are cut.

Generating more money for the arts through partnerships or innovative tax initiatives seems like a win, but local authorities will only go down this route if they truly value arts and culture, and if they can articulate this belief in a way that brings the public and businesses on side.

To this end, there has to be a role for the DCMS and the arts councils – as well as those working in the arts – in advocating for the value of art and culture for local communities and economies. Arguably central government is further along the road to understanding the value of culture than some local authorities, but there remain questions about the effectiveness of systems for trickling this information down.

There are as many different solutions to the issues posed by local authority cuts as there are local authorities. But one thing is clear: the only way forward involves all those with a vested interest in arts and culture working together.

Download AP Pulse: Local authority arts funding full report (.pdf)

Frances Richens is Editor of ArtsProfessional.