An artist, her commissioners and the council say the pressure to remove a nuclear-themed artwork was misguided. So why hasn't it been reinstalled?

Anna Lukala

An artwork removed after local councillors alleged it was a "far left wing attack" has not been returned, despite widespread condemnation of the pressure campaign.

Southend-on-Sea Borough Council says it "does not in any way condone censorship or support the approach taken by the ward councillors concerned", who promised to "take action" if the installation regarding Britain's nucelar history was not censored.

Arts company Metal said councillors James Moyies' and Derek Jarvis' "fundamental misreading" of An English Garden by Gabriella Hirst threatened to distort the actual meaning of the work.

READ MORE:

- Censorship of funded artwork 'protected our reputation', council says

- Culture of censorship in the sector as arts workers fear backlash

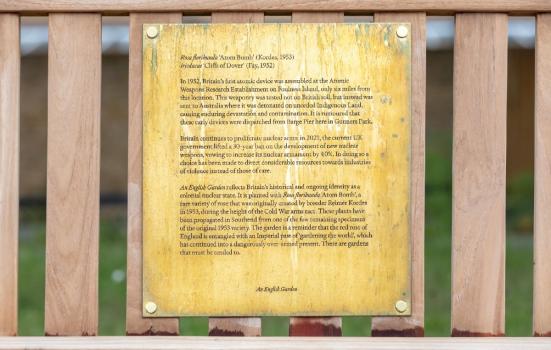

The installation, sited near where the UK's first atomic bomb was assembled, featured Cold War-era Atom Bomb roses and a plaque that explained how "Britain continues to proliferate nuclear arms" today.

"Metal took the decision to remove the work to protect the wellbeing and mental health of our small team of staff and volunteers in Southend from possible adverse effects," a statement from the company said.

"We have taken - and continue to take - action through official routes. We will keep asking questions and demanding answers and doing everything we can to fight for and protect the rights of artists and of public artworks."

But the garden has been dug up and Hirst, who objected to the removal, told ArtsProfessional she was not aware of any plans to reinstall her work.

Councillor Carole Mulroney, leader of the local authority's Liberal Democrat faction, said she offered to meet with Metal to discuss the matter further.

Metal did not respond to requests for comment.

History repeats itself

Moyies and colleagues threatened to raise their objections to the artwork in the national media if the plaque was not altered or removed within 48 hours.

But critics say doing so would have only highlighted the baselessness of the Conservatives' complaints.

Moyies interpreted Hirst's work as "attacking our country as being a colonial nuclear state" and accusing the Government of "investing in industries of hate, rather than care".

"The rest of the text has other contentious statements that I do not like, but these were the two main reasons that it had to be altered or removed," he told The Observer.

The plaque explained the nuclear history of the area as well as the current UK Government's policy to increase its nuclear stockpile by 40%, reversing decades of disarmament.

"The garden is a reminder that the red rose of England is entangled with an imperial past of 'gardening the world', which has continued into a dangerously over-armed past."

Hirst further explains: "The work aimed to hold space for the contemplation of British colonial legacy - an unavoidably complicated legacy which contains such seeming opposites as rose gardens and enduring nuclear violence."

Moyies also claimed the artwork was inappropriate to have on public land, even though the Gunners Park site is privately owned.

"Seemingly said government and its global scale nuclear arsenal was not considered robust enough to endure the airing of historical facts and critique via a rose garden art installation," Hirst said.

Offence caused

The Old Waterworks, which co-commissioned Hirst, said there had been no other negative reactions to An English Garden that it was aware of.

It says the artwork was not intended to offend ayone and that the councillors have "put words into the artist's mouth".

"There has been no positive engagement with the councillors who threatened to play out the dialogue across the media, bypassing all attempts of reasonable discussion.

"History is not not simply a celebratory fanfare and it is everyone’s right to be able to explore the nuances of this shared history and how it has ongoing impacts today."

Ceri McDade, Chair of the British Nuclear Test Veterans Association, said members were "horrified" by the garden's removal.

The Atom Bomb roses are a "poignant" reminder of British nuclear testing for the 23,000 soldiers, scientists and civilians involved.

"Participation in this testing and the quest for a nuclear deterrent is as relevant to our veterans and their families in 2021 as it was in 1952 and should not be swept under the carpet."

The association vowed to ensure "that this part of history is not forgotten or re-written".