The arts and the other creative industries may not always make comfortable bedfellows, but there are enough good reasons for them to sleep together, says Liz Hill.

opensource.com (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The creative industries grew by almost 10% in 2012, outperforming every other sector of UK industry. Worth £71.4bn to the UK economy, they accounted for 1.68m jobs, and politicians bask in their international glow, which apparently drives economic growth, investment and tourism. But behind these headlines lie a series of tensions, and the Warwick Commission Creative and Cultural Leaders Summit last week drew a number of these to the surface, exposing some of the raw nerves that explain why the arts sector sometimes finds its creative industries counterparts – such as advertising, design, film, software and publishing – to be somewhat uncomfortable bedfellows.

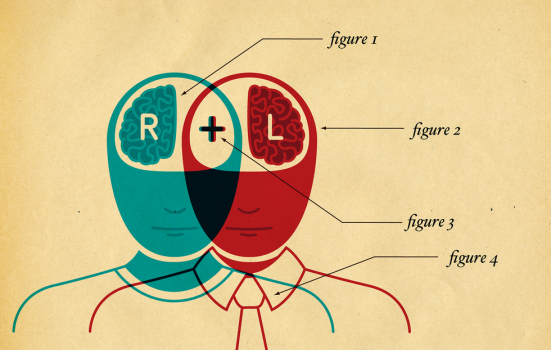

The first speaker, Terry Tyrrell, Chairman of the agency Brand Union, grappled with the question of whether it is possible to build a 'brand' across the creative and cultural sectors, and if so, how it could be achieved and what the benefits would be. Apparently, a brand is all about reputation – “what people say about you when you leave the room.” But the fragmented nature of the creative industries makes it hard for the public – and perhaps more to the point, politicians – to understand and appreciate their value. Could this be where a cross-sectoral branding exercise might come in, to develop some sort of internalised “brand manifesto” that the different industries sign up to? Thankfully, the idea of some monolithic FIFA-like umbrella brand embracing the whole of the creative industries was quickly dismissed in favour of a “multi-brand” approach, like the BBC, with all its sub-brands reaching out to diverse audiences whilst maintaining a single underlying set of values. Could this be a helpful example of how a whole can be greater than the sum of its parts? Could being “unified, but not uniform” deliver a more powerful message about the value of the creative industries than individual creative “silos” can ever hope to do?

the arts do not enjoy the approval of all sectors of society and surely a more effective conversation with the public is a necessary precursor to more effective conversations with Government

Well, potentially yes. The second speaker was Simon Anholt, founder of Anholt-GfK Roper Nation Brands Index, who reflected on the brand image of Britain from abroad and the extraordinary extent to which the combined attributes of the creative and cultural industries contribute to it being the 3rd most admired country in the world. His observations on how Britain’s collective creative heartbeat is being viewed enviously by the rest of the world were enough to ignite a moment of national pride in even the most hardened of cynics. Apparently, if people believe that a country has a powerful cultural heritage and strong creative industries, they see self-respect. It’s a quality that is internationally admired and generates the much-coveted “soft power” that helps politicians to attract and co-opt, rather than use force or give money, as a means of persuasion. Not bad for a country that is clean out of hard power these days. But viewed from at home, the picture of the creative and cultural sector is very different. Overlooked and undervalued by politicians, could the creative industries develop the same sort of brand appeal at home as they enjoy elsewhere, if only they were to speak with a unified voice? What are the ‘cracks’ that are weakening the influence of the creative and cultural sector at home, and could more consistent branding be the ‘glue’ that holds it all together?

When the assembled gathering of senior cultural and creative leaders was asked to discuss the latter, it quickly became clear that not everyone buys into the metaphor of the creative industries as a broken pot that needs fixing. “Believers” and “non-believers” made their cases, but from an arts perspective the ‘cracks’ started to look more like fault lines. For example, to what extent do the interests of powerful global marketing services corporations such as WPP, the world's largest communications services group which employs around 170,000 people in 3,000 offices across 110 countries, align with those of the UK’s arts organisations which, with the exception of a dozen or so mainly London-based institutions, are almost exclusively SMEs employing fewer than 250 people? Even ATG, with 3,500 employees and 40 venues across 36 locations, is a minnow in comparison. Motivation is another great divider. Whilst the commercial arm of the arts sector is busy maximising returns to shareholders, just like most other creative sector businesses, the whole point of the contribution made by artists and arts organisations in the not-for-profit arm of the arts is creative expression: financial viability is necessary, but financial return is certainly not. It’s a pretty fundamental difference, and one that lies at the root of the need for arts funding. Somehow, the idea that those creative individuals will respond to a team of brand police hoping to get the different creative sectors to line up behind some sort of collective message or purpose is difficult to imagine (unless they are required to demonstrate this in their funding applications, of course). Indeed, could it be that, far from hindering progress, individualism and absence of collective purpose are among the reasons why the creative industries have triumphed, relatively speaking, in the midst of world political and economic turmoil and growing cynicism about the ethics of the corporate world?

But for me, perhaps the biggest barrier to agreeing any brand proposition across the creative industries is precisely what the Warwick Commission is looking into – cultural value. Because whilst the wider public puts its money where its mouth is to demonstrate the value it places on the creative output of sectors such as gaming, film and fashion, there is no such demonstration of support for much of the arts. Despite all attempts at being diverse, inclusive and accessible, public perceptions of the arts are still associated with “snobbery and elitism” (according to a design agency delegate who took part in one of the discussion groups). Whilst those of us working in the arts might prefer to phrase it that too many people feel the arts are ‘not for them’, maybe we’re just arguing semantics. Unlike other parts of the creative industries, the arts do not enjoy the approval of all sectors of society and surely a more effective conversation with the public is a necessary precursor to more effective conversations with Government.

So, do the arts and the other creative industries need each other sufficiently for any form of collaboration to make sense? By focusing on “common causes”, rather than suggesting that we could all be one big happy family, John Kampfner and John Sorrell, Director and Chair respectively of the fledgling Creative Industries Federation (CIF), who were the final contributors to the debate, managed to persuade me – and others – that they do. “Who do I call if I want to call Europe?” US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger is widely quoted as having said. And the same question is raised by our own politicians about the creative and cultural sectors, according to Sorrell, who as a member of the Government’s Creative Industries Council has witnessed first-hand the impact of “too many people shouting about their specific industries”. What’s missing is a single, independent voice that can represent the common needs of the sector – like the need for strong creative and cultural education in schools. Sorrell believes that the absence of such a body left the creative sector fighting a rear-guard action when Education Secretary Michael Gove made moves to demote the position of the arts in schools. Better to be consulted in advance on policy initiatives than to have to campaign retrospectively against them when ill-conceived plans are already on the table.

The CIF is set for an official launch in September and you couldn’t blame the arts sector for wanting to ignore it – especially the small and cash-strapped, those with strong links to existing representative bodies, and those whose work aligns them more closely with health, education or public services than with their more glamourous commercial counterparts. But that could be a serious mistake. Leaders of some of the most prestigious and respected organisations and institutions across the creative and cultural industries have already pledged their involvement, and as a result they will undoubtedly gain the ear of Government. If their voices are the only ones that are heard, the tensions in the arts – between large and small organisations, London and the regions, funded and un-funded, artists and arts organisations – can only get worse. Far better for the whole of the sector to get on board with this new initiative from the start, influencing its course to steer, than waking up later only to find that the boat has left without them and is going in the wrong direction.

Liz Hill is Editor of ArtsProfessional.

www.artsprofessional.co.uk