Friends schemes are a source of both pleasure and pain for many arts managers. Comprising an organisation's most staunch supporters, they can create a pool of fiercely loyal advocates as well as generate a valuable revenue stream. But all too often, a relationship with the potential to develop into a mutually beneficial long-term partnership can more closely resemble a marriage of convenience. Kim Horan reports on preliminary findings from the latest pilot study into Friends schemes and identifies the key issues.

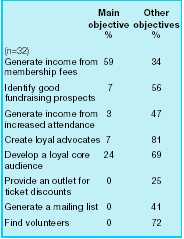

Friends schemes exist for a variety of different reasons, but fundamentally these all fall into just two categories: those where the primary objective is to generate revenues, and those which aim primarily to cultivate loyalty to the organisation. The revenue-generators outnumber the loyalty-seekers by approximately 2:1 (fig.1), and the good news for them is that over two-thirds of respondents to the pilot survey of Friends of arts organisations say that there is never or rarely any resistance by potential Friends to paying membership fees. Clearly Friends schemes have the potential to generate a rich seam of income for organisations which successfully tap into them. The more successful schemes in the survey, some with memberships running into several thousands and located across the UK, not just in London, reported net incomes of over £30 per head from their Friends schemes. As many as a third of respondents agreed with the statement "the organisation would struggle financially without the revenues generated from the Friends"; and budgets of up to £65,000 were reported as being allocated to the management and development of larger schemes.

Chicken and egg

Less impressive is the fact that, whilst the vast majority of organisations are able to put an approximate figure to the income generated from Friends 'membership fees in the last financial year, only just over a third had any information about the costs of running their schemes, and over half reported difficulties with the process of evaluating the true costs. So it's hardly surprising that two thirds of organisations cited lack of funding or resources to develop their Friends scheme as a problem for them. Its a chicken and egg situation. Budgets can't be justified for activity that doesn't generate demonstrable financial benefits; so schemes remain embryonic, their full potential is unrecognised, and no one believes that an investment in nurturing a fledgling scheme or revitalising a tired one is worthwhile.

Staying Friends

Neglect is a sure-fire way of alienating Friends and ensuring that a scheme - or worse still, the organisation - ceases to be attractive to potential members. One regional theatre said of its new scheme "This particular scheme has run for three years:the old one disintegrated because there was no key member of staff in place to look after it. Original members were invited to join the new scheme but take- up was quite low." Clearly, if a Friends scheme is to be valuable to an organisation, the Friends themselves must be valued by that organisation, and treated as a high priority group - not an administrative problem. Most organisations agreed that their Friends are the bedrock of the organisation's regular attenders: this loyal core of supporters generally considers itself to be more than just a fundraising body. Friends want to support more. This is a relationship, and as with any relationship, that needs to be worked at. The organisation is undoubtedly happy to take its Friends' money but is it willing to take on board their opinions? Being inattentive to the needs of the most committed of loyal supporters can disengage the very sector of the audience that is most relied upon.

Buying loyalty

As for those whose schemes aim primarily to cultivate loyalty, their problems are not so much about measuring the net income generated by their scheme, but about the extent to which their scheme encourages the commitment of its members. It's relatively easy to design a scheme which buys loyalty by offering special ticket deals and opportunities to 'jump the queue' for popular events; and initial findings in this study suggest that the type of scheme benefits generally found most attractive by Friends are those which provide better, cheaper or easier access to the artistic product. Advance programme information, priority booking, and free or discounted tickets are particularly popular and most effective when not confused with other subscription or discount schemes. However, creating a scheme which encourages a passion for an artform and offers a higher level of involvement is something else entirely, though not necessarily mutually exclusive from generating income. The most effective benefits to provide for those who are interested in "unravelling the mysteries of their chosen artform "seem to be those which create exclusive opportunities to access their chosen artform. Invitations to rehearsals or private viewings, opportunities to meet artists or actors and backstage or archive tours, which cannot be accessed other than through the Friends, all create positive reasons for involvement with Friends organisations, and are generally found to be effective. Far less effective examples of benefits have been quiz nights, shopping trips and celebrity cookbooks. This seems to be a matter of relevance and exclusivity. Friends want their arts organisation to be doing what they do best, i.e. theatre, making music, exhibiting works of art, rather than wasting time and resources on social events that can be provided elsewhere.

Growing pains

The key challenge facing managers is developing their Friends schemes to successfully identify the particular mix of benefits and membership price levels that will be attractive to potential Friends; so the fact that nearly three quarters of respondents found lack of research or feedback to inform the development of their schemes to be a problem is clearly an issue that needs to be addressed if the schemes are to be helped to grow and flourish. Another dilemma facing managers hoping to extend the reach of their Friends schemes is how to manage success if it arrives. Schemes which are independent entities, separate from the organisation and run entirely by volunteers, are seldom in a position to manage a complex membership database, and the tasks of recruitment, renewal, and communication with members can be onerous for them to manage efficiently. On the other hand, schemes which are run in-house by the arts organisations themselves tend to suffer from their managers having multiple priorities, of which the Friends are but one. The way forward as always, is to invest resources; and it is the organisations which take the trouble to both evaluate the benefits and count the costs of their Friends schemes who are in the best position to negotiate for the budgets that will allow them to achieve the levels of support already being realised by the best. It is vital that a better level of understanding is reached into what Friends really want so that investment and development can reach its full potential. It is unlikely that those who procrastinate on investment and evaluation will ever increase their Friends membership, whatever the objectives of their scheme may be.

Kim Horan is Special Projects Manager for Arts Intelligence Ltd. t:01954 250600 e:kim@artsprofessional.co.uk She is interested in hearing from arts organisations willing to participate in further research into Friends organisations. A pilot survey of 32 UK-based arts organisations with Friends schemes was conducted in October 2001 by Arts Intelligence Ltd, with a view to generating baseline information to inform the design of a more comprehensive survey next year.