?Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community [and] to enjoy the arts? according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 27. A great statement but where does it take us? ask Clare Connor and Jonathan Goodacre, who explore the meaning of social inclusion work in the arts.

?Cultural life? can mean different things to different people. Skaters (skateboarders and inliners), for example, as activists and dwellers of social spaces offer a counterculture in which they reinterpret architecture, using it as an instrument and terrain for spontaneous composition inviting sensory rhythms and physical dexterity (now wouldn?t that make good dance copy?!). Who has the right to value and encourage one particular activity above another? If the aim of social inclusion is to address inequality and improve access to the mainstream then we need to be explicit and recognise that this is not a one-way street and we all have something to learn.

So what is social inclusion? And is it worth doing? First, let?s understand social exclusion. We are all excluded from certain communities at some time in our lives, but here we are describing wholesale exclusion from ?mainstream? society. The Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey (Bristol University, 1999) refers to four types of exclusion: from adequate income, from the labour market, from services and from social relations. Encouraging people with low incomes to attend an arts event will not make social exclusion go away. To argue that this is what social inclusion is about is merely setting up a false premise which can easily be shot down.

Decision-making

Social inclusion requires a commitment to placing the individual at the centre of a process rather than as passive recipient of a scheme, or as part of a sedentary audience. In our experience, potential participants are extremely sensitive to being picked on for social inclusion schemes. After all, how would you like to be told that you are a problem?

We were confronted with this issue in Southend-on-Sea when we approached a young mothers group in the town. They were naturally sceptical of people who wanted to deal with their ?problem? and so we were faced with some hostility. Luckily, we were working with experienced youth workers whose experience and skills provided a bridge between the artistic facilitators and the group. Creating space for groups of individuals to be self-defining around issues which they themselves have chosen goes some way towards alleviating negative stereotypes.

We recognise it has been important to begin the process ?in credit? with respect for others. It allows questions to be asked and creates an environment in which the managers of the project can be facilitators rather than proscribers. Rather than wanting to be changed, we?ve found that what participants want is access to resources, skills sharing and guidance in achieving personal aims.

Allowing time for reflection through evaluation is vital and there?s a great temptation to want to problem-solve everything. After all, we want to work with integrity and at the same time satisfy the funders. If we are truly serious about this work, we need to listen carefully to the stories emanating from the work, both good and bad. They provide the critical learning points which can guide development.

Creative programme design

Projects need to take into account the range of circumstances unique to every individual, group, location and partnership. Matching the top-down and bottom-up aspects of social inclusion work is difficult and as an agency we spend a lot of time trying to balance the two. However, policy initiatives do help promote awareness among partners (enabling support through a repertoire of local networks). They can unlock valuable resources and provide an ongoing component of a programme.

Social inclusion work is, by its very nature, a collaborative process. In the case of the Southend-on-Sea project (?Being Here?) there were already organisations with a wealth of experience in the fields of Youth Service, Project Management, Community Partnership, Artistic Facilitation and Family Work. The project to date has not set out to redefine or replace these partner organisations but to add value, making creative connections between organisations. The partnership has been a place for questioning, reshaping, sourcing, resourcing, steering and developing practice and knowledge.

Quality and the mainstream

Art demands a rigour in conceptual thought and process, which arguably improves with practice and guidance, but talent does not sit exclusively with those who undertake it for a living. There are interesting debates around perceived distinctions between ?community? art and ?professional? art. Community art, so the argument goes, is all very well for the participants but it isn?t ?quality? and shouldn?t be confused with proper art.

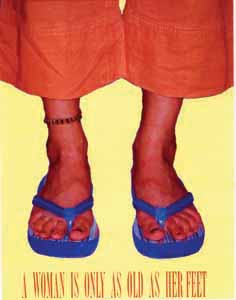

This view needs countering. The excitement generated from Being Here has been fantastic. For example, a poster displayed at a conference delighted delegates so much they demanded to know where they could buy it. A flag produced by skaters and flown from the roof of a building in Southend-on-Sea produced such admiration and outrage that local residents demanded it be taken down. Many so-called conceptual artists would have been proud of such an outcome!

Challenge and reward

This sort of project requires lateral thinking, subversion of hierarchies, significant and long-term funding and often a high ratio of people to participants. It embodies working with the unexpected and accepting alternative and different types of outcome. Disappointments and feelings of failure experienced by individuals and groups are often a result of inconsistency and not inability. With time and patience they can be balanced and rewarded by small but significant changes.

The benefits of social inclusion work can be witnessed when arts organisations are working with as well as for communities. At its best, it promotes mobility of thought and physical access, and the alternative use of local spaces. It brings in resources to develop ongoing initiatives, and provides opportunity, support and creative facilitation driven by the individuals concerned.

Who needs to learn?

Typically in these projects, much emphasis is placed on bringing about change in the individual. After all, we?re tackling social exclusion aren?t we? However, we now realise that making a difference to people?s lives is all well and good, but perhaps the difference is not always with the people we might expect; more likely it is with the project leaders, with those making the policy initiatives and in our own organisations.

The Mercury Theatre in Colchester has undertaken extensive social inclusion work over a number of years, including work with the North East Essex Youth Offending team. It is part of the annual programme and features exchange and training for the main stage actors, community and outreach artists, staff and senior management. There is a sense of parity between each area of work at The Mercury. Their programme requires an investigation of what can be shared in all aspects of the life of the theatre and how the learning crosses departments. There is an investment in the development of the skills of those accessing the organisation, a sense of sharing and a rejection of the inherited status, which usually sees education work as secondary to the main stage programme.

The essential paradox is not that the participants are transformed by their participation in an artistic process, but that they transform others by allowing them to see or be part of the process or outcome. It often produces works of great integrity and usually demands that arts organisations, artists and arts professionals readdress their own attitudes and practices.

Let?s stop pretending we are doing excluded groups a favour. How about we recognise that we are all have something to gain from engaging with this work?

Clare Connor is Creative Director and Jonathan Goodacre is Marketing Development Manager at Eastern Touring Agency. Work from the Being Here project is on display at The Cliffs Pavilion, Westcliff-on-Sea and Southend Central Railway Station until November 8. ETA is hosting ?Out of the Tickbox?, a conference on social inclusion in the arts at The Mercury Theatre, Colchester on November 14. For details

t: 01223 500202 e: info@e-t-a.org.uk