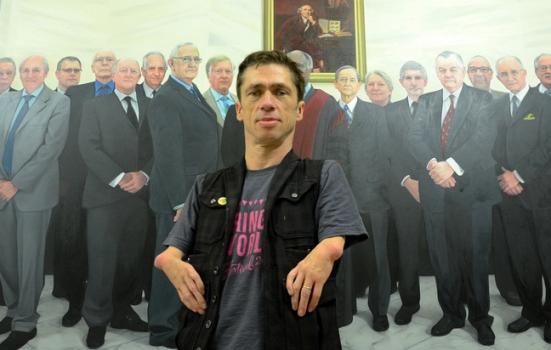

Mat Fraser focuses his disability activism on how exhibitions in medical museums can change ideas and attitudes around disability.

Richard Sandell

I was first involved with museums and disability more than 15 years ago in Colchester when I was invited to take part in a day on disability representation in museums. It opened up the whole subject for me, as it was not one I had really previously considered. From there I was asked by Richard Sandell and Jocelyn Dodd at the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries at the University of Leicester to take part in a UK-wide Heritage Lottery-funded action research project designed to tackle the under- and misrepresentation of disabled people in museums and art galleries (called Rethinking Disability Representation).

Following this, I started to think about museums in a completely different way, realising how influential they can be on young brains and their potential for informing many people about disability. My disability activism through performances had, up until that point, been strictly through theatre cabaret and other stages, but I started thinking about the part museums could play in helping to positively shape ideas and attitudes around disability.

It almost never included the human aspect of the disabled person who used the equipment or interacted with the professionals

A few years later Richard and Jocelyn approached me with the idea of making a performance relating to the subject of the presentation of disability-related material in exhibitions. It was fascinating, as there was so much material to look at and consider, due to the inclusion of the Royal College of Physicians, the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons and the Science Museum as museum partners, with help from Shape and funding from the Wellcome Trust. The sheer volume of disability-related material was almost overwhelming.

Through my exploration of the museum collections it was easy to see how attitudes to disability have changed over the years, such as the descriptions of artefacts and the explanations of impairments and equipment, alongside the paraphernalia of medicine and healthcare over the centuries. Pretty much 100% of it was viewed through the prism of the medical model of disability (viewing disability as a problem of the person, directly caused by disease, trauma or other health condition requiring medical care), from the professional or clinician’s point of view. It almost never included the human aspect of the disabled person who used the equipment or interacted with the professionals. As time has progressed, the medical model was often replaced with the charity model (disabled people regarded as victims of circumstance who are deserving of pity), but again this does, and did, little to promote the full human status and equality disabled people should be experiencing today. Part of the reason that they do not is due to museums colluding with these historical ways of understanding disabled people and so misunderstanding them. There have been some examples of better practice and attempts to address this awful imbalance in various museum projects around the UK over the last ten years. This is a good beginning, better late than never, but much more needs to be done.

Today's attitudes to disability are of course vastly improved, but still have a very long way to go. The Paralympics of 2012 helped to raise the profile of disability, but propagated the notion of triumph over tragedy, of disabled people needing to half kill themselves going for gold in order to validate their existence. At the same time the Government is systematically attacking us, and the return of the notion of the disabled as a drain on society is coming back. So much of the good public relations work done in the last 25 years is being eroded.

Today, outmoded notions of disabled people as quiet recipients of charitable medicine and institutionalised living seem a thing of the distant past. This is a marked improvement, and an understanding of disabled people as equals is growing. But without more backing from cultural places such as museums, this will not reach a satisfactory conclusion for many years to come. Thus, it is the responsibility of museums to improve their practice around disability, and have that improvement manifest itself most obviously in their exhibitions.

I have performed my show ‘Cabinet of Curiosities – how disability was kept in a box’ in science and medical museums including the Royal College of Physicians and the Hunterian Museum. I hope that audiences left with an understanding of how disabled people used to be viewed in such unequal ways, how that related to industrialisation, Victorian sensibilities and how the medical profession's desire for status colluded in that, as well as charitable and religious forces that decided we should be hidden away from view for corrective treatments. I would hope that audiences could see how society changed with mechanisation, then with post-war social concerns, leading to relative emancipation from the 1970s onwards. Ultimately, I want people to leave with a more informed, equitable and respectful way of understanding disabled people, each other, all of us, society.

Mat Fraser is a writer and actor.

www.matfraser.co.uk