Andrew Ormston explains how hand-in-hand scientists and artists are colonising new, barren land. Just like fungi and algae

The academy’s fracturing of the sciences and the arts is under some scrutiny at present. C.P. Snow sounded the alarm with his attack on ‘the two cultures’ half a century ago and things seem to be getting worse. We have to choose between the two disciplines early in our school careers and by the time higher education beckons the separation is complete. This, in a world where almost the only thing we know about our future with any certainty is that we do not know enough, and where the scientific project is both enormously complex and shaped by a wide range of external interests and pressures.

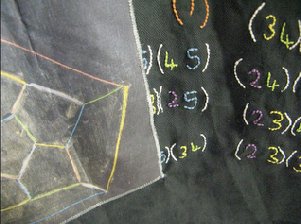

So while universities, institutes and research councils begin to catch up with the trans-disciplinary zeitgeist, many scientists and artists have taken the initiative themselves. One such network is ASCUS, taking its name from the world of lichen – the ascus is where spores are produced, which then colonise new, barren areas of the world. Itself an organ, the ascus is a structure formed by a symbiosis of organisms from the very different kingdoms of fungi and plants; just as we at ASCUS are a symbiosis of artists and scientists.

From its beginnings in 2008, ASCUS has grown to a network of over 300 international scientists and artists, all committed to the practice of collaboration between the disciplines. The early years saw geoscientists from the University of Edinburgh organise field trips and exhibitions. Charles Jenck’s Garden of Cosmic Speculation and Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Little Sparta provided inspiration for a range of panel discussions, public talks and exhibitions. In 2011 ASCUS was invited to deliver the Edinburgh Beltane art-science collaboration grants scheme, selecting commissions and working with the chosen teams.

For some the regular ASCUS evening presentations and talks remain the most important part of the network’s programme. The informal meetings make good use of the back rooms of Edinburgh’s historic hostelries and consider a wide range of presentations; from collaborators researching land use in Africa to quantum mechanics in Scotland. Participants continue to be astounded by the range and innovation of collaborations that are developed across the disciplines.

ASCUS is now working to widen the net for art and science collaborations by introducing the results into the public domain. A pop up gallery in Edinburgh’s main shopping mall, the St James Centre, is exhibiting the results of the Beltane commissions and providing a venue for a range of associated events. The gallery is staffed by network volunteers, providing visitors with the opportunity to meet and find out more about the work of ASCUS members. In April ASCUS will deliver a science and art installation at the City Arts Centre in Edinburgh for the Edinburgh International Science Festival.

All of this has been achieved with the help of volunteer network participants and a multi-skilled ‘committee’ of scientists, geographers, artists, architects, and curators. ASCUS aspires to continue to be an open network for collaborative work and research, but to also provide a range of tools and platforms to further support scientists and artists. A priority is an open online site with interactive features that can support the development of actual collaborations between scientists and artists.

The ‘sciart’ field is characterised by clusters of practice across the world. There are real pioneers in the field; people like Cynthia Pannucci in America, Gavin Artz in Australia, and Nicola Triscott of the Arts Catalyst in London. But bringing people together is difficult and identifying the resources required to embed ‘sciart’ in education and research is not easy.

ASCUS is planning a route that will maintain an open network, where any scientist or artist interested in collaboration can find something of relevance and value to their ambitions. It also plans to introduce stronger governance and organisational capacity during 2012, while responding to the increasing demands from potential partners for collaborative working. It’s going to be a busy year.

Andrew Ormston is Director of Drew Wylie Ltd, providing business and policy development advice in the cultural and creative industries.

W www.drewwylie.net

W www.ascus.org.uk

E andrew@drewwylie.net