Steven Warner and Stephanie Cesana give a trade union’s perspective on the role of volunteers in arts organisations

Britain is noted for its volunteering culture. Giving something back is a powerful instinct in our national fabric and, as a result, society has benefited from this fund of goodwill. In recent times, the ethos of volunteering has gained popularity as the Tory-led coalition government unveiled its flagship policy in building ‘The Big Society’.

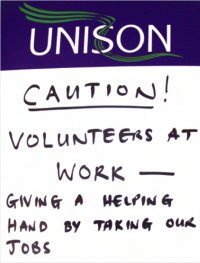

On volunteering opportunities, Unison – the largest public sector trade union – has adopted a position similar to its stance on the challenge of privatisation and compulsory tendering. It argues against volunteering in delivering services and warns of the dangers of job substitution by placing volunteers in key roles that were previously filled by paid staff. Whilst Unison recognises that volunteers can make a valuable contribution to an organisation, the union opposes the use of volunteers to replace paid staff.

In both the public and private sector, the volunteering trend is now gathering pace in the arts. Following the Government’s spending review, cash-strapped local authorities up and down the country are being forced into privatising their theatres to commercial operators, and the temptation is for such operators servicing local authority contracts to show an unhealthy interest in volunteers by recruiting armies of goodwill ambassadors in an effort to maximise profits by reducing staffing and contract costs.

Unison has been following the case of a group of 25 workers, predominantly women, on low incomes engaged in ushering and front of house duties who were all transferred to a commercial operator under TUPE – Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) – regulations, but due to new voluntary activity have been left with little or no work despite numerous pledges from the Council and their new employer that their employment would be protected. The volunteer recruitment drive referred to the volunteers as ‘ushers’, and Unison is concerned that there was not a sufficient difference between volunteer ‘meeters and greeters’ and paid staff, and that this was simply a ploy to reduce contract costs and use volunteers as a cut-price alternative to paid staff.

It is the lack of clarity in distinguishing the roles of volunteers and those of paid staff apparently carrying out the same duties that is at the heart of the problem. Where someone is performing tasks that would normally be carried out by paid workers, this would imply job substitution and does not equate to good volunteering practice. Volunteering England considers volunteers are being substituted for paid employment if they are:

• Working for a commercial or profit-making organisation

• Performing jobs or tasks that were formerly carried out by paid employees

• Performing jobs or tasks, which, because of their continuous, repetitive or unattractive nature require to be paid

• Performing jobs or tasks for employees who are in dispute with their employer.

In general, it is not seen as acceptable for people to volunteer in the commercial sector, but if volunteers are engaged at ‘for profit’ venues, they are used to add value by complementing and supplementing the work of paid staff, without replacing them. In some public sectors too, such as in the NHS, the library service and the police, Unison has also objected and campaigned strongly about this practice, as it appears to undercut the status and wages of paid staff and to exploit the time and skills of unpaid volunteers.

A related issue is the provision of a financial inducement for performing a job or task. If an inducement is offered, Unison says it should be at the market rate for the job, with the recognition that the individual is an employee and not a volunteer. Rewarding volunteers with theatre ticket vouchers and other benefits every time they appear for work implies a employment relationship. It is Volunteering England’s view that “by giving volunteers a reward with an economic value… [a theatre] could be seen to be creating a contract of employment under the National Minimum Wage Act, which could confer employment rights on the ‘volunteers’ and open the Theatre to investigation by HM Revenue and Customs.” Volunteering England recommends that volunteers should only be reimbursed for expenses incurred in the course of carrying out the role and that receipts should be provided for this purpose. In addition, if a volunteer is in receipt of state benefits, Jobcentre Plus and HM Revenue and Customs can investigate instances of suspected ‘notional earnings’.

As for the ushers who now find themselves without work, one commented: “The whole process has been very traumatic and upsetting and can only be viewed as a vicious attack on our jobs which has left all of us displaced and essentially without work. We will continue to voice our opposition and campaign against the volunteering measures…”

In 2009, the TUC (Trades Union Congress) and Volunteering England agreed on a set of key principles on which volunteering is organised and how good relations between paid staff and volunteers are built. ‘The Charter for Strengthening Relations Between Paid Staff and Volunteers’ is a valuable starting point for any organisation thinking of involving volunteers. To avoid potential disputes, organisations involving volunteers should make it their duty to keep abreast of good practice in volunteer management. Organisations must understand both the good practice and legal implications of volunteer involvement in order to ensure that volunteering remains a valuable and harmonious experience for all.

The Charter for strengthening relations between paid staff and volunteers highlights the following points:

• All volunteering is undertaken by choice, and all individuals should have the right to volunteer, or indeed not to volunteer

• While volunteers should not normally receive or expect financial rewards for their activities, they should receive reasonable out of pocket expenses

• The involvement of volunteers should complement and supplement the work of paid staff, and should not be used to displace paid staff or undercut their pay and conditions of service

• The added value of volunteers should be highlighted as part of commissioning or grant making processes but their involvement should not be used to reduce contract costs

• Effective structures should be put in place to support and develop volunteers and the activities they undertake, and these should be fully considered and costed when services are planned and developed

• Volunteers and paid staff should be provided with opportunities to contribute to the development of volunteering policies and procedures

• Volunteers, like paid staff, should be able to carry out their duties in safe, secure and healthy environments that are free from harassment, intimidation, bullying, violence and discrimination

• All paid workers and volunteers should have access to appropriate training and development

• There should be recognised processes for the resolution of any problems between organisations and volunteers or between paid staff and volunteers

• In the interests of harmonious relations between volunteers and paid staff, volunteers should not be used to undertake the work of paid staff during industrial disputes.

Lucy McLynn explains the legal position of casual workers and volunteers

The term ‘casual workers’ can cover a number of arrangements, from the truly ‘casual’, who work from time to time when they wish to do so, to workers who are called ‘casual’ but in reality work week-in week-out and are effectively part-time employees. Even true casuals may well have some protection under employment law – for instance the right not to be discriminated against on any unlawful ground (sex, race, age, etc), as well as the right not to be treated less favourably on the ground of their part-time status. When a business transfers from one owner to another, the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations (TUPE) protect only those who are employees and assigned to a particular undertaking “other than on a temporary basis”. Whilst dispensing with casuals when an undertaking transfers may not trigger protection under TUPE it may well give rise to claims for discrimination or less favourable treatment.

There is not necessarily a legal problem with using volunteers to replace casual workers (or even employees), whether after a transfer or at another time. Providing volunteers with tangible benefits which are not necessary for the performance of the volunteering activities is dangerous for an organisation, however, as it risks taking the arrangement away from being voluntary on both sides and turning it into a commercial bargain. It is then likely to be a contractual relationship. This has implications in terms of employment law protections for volunteers, not least entitlement to National Minimum Wage (from which voluntary workers under a contract are exempt if they receive only out of pocket expenses and no other valuable benefits). Volunteers who are under a contract personally to provide their services are protected from discrimination, and may even have protection from unfair dismissal.

Lucy McLynn is Partner – Employment Department at Bates Wells & Braithwaite London LLP.

W www.bwbllp.com

Mahmood Reza clarifies the payment and tax situation relating to volunteers

The nature of the relationship between an organisation and an individual determines the tax treatment of any subsequent payments made to that individual. If there is no employment relationship then the organisation is not governed by national minimum wage (NMW) regulations. A person’s status depends on the circumstances under which they work and whether they are performing as a ‘worker’. Key elements in establishing whether someone is a worker include whether there is an obligation on the individual to perform the work and in return an obligation on you to provide the work.

It is worth noting that ‘voluntary worker’ is a term used in the National Minimum Wage Act 1998 and has a specific meaning for NMW purposes. Voluntary workers can only be engaged by a charity, voluntary organisation, an associated fundraising body or statutory body; they may call themselves volunteers but they are in fact workers due to the arrangements under which they work. This exemption is designed to allow people who genuinely wish to work without profit for good causes to continue to do so without fear of qualifying for the NMW. However, voluntary workers may not receive any monetary payment apart from the reimbursement of expenses incurred in the performance of duties or to enable the worker to perform their duties.

An organisation is permitted to pay volunteers (and avoid a tax charge) as long as it merely reimburses the costs incurred, or paid at approved scale rates, such as mileage at a rate approved by the tax office. If the volunteer ‘profits’, say through receiving vouchers, round sum allowances or other benefits in kind, then this may be considered disguised remuneration. If this happens then PAYE may apply, with all the attendant forms and declarations. If the volunteer receives social security benefits then additional problems can arise.

Mahmood Reza is Proprietor of Pro Active Resolutions.

E mahmood@proactiveresolutions.com