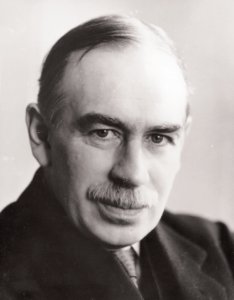

The central role played by Arts Council England in the development of the arts in this country is one that continues to stimulate impassioned debate and controversy across the sector. Sir Christopher Frayling considers the vision of founder John Maynard Keynes, and examines whether an Arts Council is still required.

On 12 June 1945, John Maynard Keynes, sitting next to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, launched the Arts Council with a speech at a press conference, which was adapted into a BBC radio broadcast a few days later. It was headed The Arts Council its policy and hopes. The speech began with the wartime story of CEMA the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts which had, as Keynes put it, when our spirits were at a low ebb& carried music, drama and pictures to places which otherwise would be cut off from the masterpieces of happier times. This had originated as a protection of the best in our culture against the barbarians putting a wall round the arts but soon, as Keynes said, we found [to our surprise] that we were providing what had never existed even in peacetime, and that there was a much larger public out there than his Bloomsbury circle had ever anticipated. So CEMA had turned into a social as well as artistic service, almost despite itself; and this in turn directly led to the foundation of the Arts Council: I do not believe it is yet realised what a very important thing has happened. State patronage of the arts, entirely supported by the Treasury, has crept in. It has happened in a very English, informal unostentatious way.

Beveridge had talked of slaying the five giants of physical poverty the NHS and public education were to be the result but what about a sixth, poverty of aspiration, which engagement with the arts could help to improve?

Early priorities

The first priority the prime function of the Arts Council would be to ensure that although money for the arts came from the public purse, the independence of the artist and the arts organisation would be protected at all costs. There was much talk in the air of nationalising industry, but that was rejected for the arts. There would be no nationalisation of culture: The artist walks where the breath of the spirit blows him. He cannot be told his direction; he does not know it himself. But he leads the rest of us into fresh pastures and teaches us to love and to enjoy what we often begin by rejecting, enlarging our sensibility and purifying our instincts. The task of an official body is not to censor, but give courage, confidence and opportunity.

So although the Council was ultimately responsible to Parliament, which will have to be satisfied with what we are doing, satisfied with the spending of public money, the Council also had to be as independent as possible. This came to be known as the arms-length principle, and it was a large part of the point. The government would provide money, policy and silence. The Council would be accountable to government.

The second priority was to listen to the lessons of wartime, and open the doors as widely as convenient to the masterpieces of happier times. Important opera companies, theatre troupes and orchestras were on the brink of bankruptcy and the new Arts Council would do what it could in partnership with others, through a complex system of grants and loans about these.

The third priority was the buildings in which the art would happen. The urgent rebuilding of blitzed, blacked out and evacuated cities and towns should, Keynes said, be accompanied by the rebuilding of the culture as well as was happening so successfully in the Soviet Union. This would, of course, have to be largely a matter for local authorities and local enterprise, because the Arts Council would never have enough money for such a project. But there could be no better memorial of a war to save the freedom of the spirit of the individual. We look forward to the time when the theatre and the concert hall and the gallery will be a living element in everyones upbringing and regular attendance at the theatre and at concerts a part of organised education.

New visions

This would mean working through the ten regional offices of CEMA, based on the early warning regions which had sounded the sirens in the war before becoming staging posts for the arts. It would also mean razing London, Phoenix-like, as a great artistic metropolis out of the rubble of the blitz. What if Covent Garden could show opera again, rather than belonging to Mecca Cafés? What if there were to be a National Theatre? What if Sadlers Wells (now the Royal Ballet) and Sadlers Wells Opera (now English National Opera) could find new or permanent homes? And what if every city had its own theatre, gallery and concert hall. What if?

All this was soon to be distilled into the Arts Councils Charter, granted in summer 1946. Keynes drafted it, but died on Easter Sunday 1946 before it was ratified: to increase the accessibility of the arts to the public; to improve standards in the arts; to encourage people to participate in the arts; to advise and co-operate with government departments and local authorities in any matters concerned with these purposes.

Keyness speech of June 1945, and indeed the Charter (as charters always do), contained all sorts of ambiguities: how would co-operation with government departments actually work? access, excellence or both? the best or the most or both? professionals and/or amateurs? housing the arts and/or running the arts? London and the regions? relationships with local authorities? And so on.

The total grant to the Arts Council in 1946 was £235,000 that is £29m in todays money. The Council supported 22 theatres and 8 orchestras, and all was well with the world. Most of the money went on the new Royal Opera, Sadlers Wells, the Old Vic and the orchestras. Over the next few years, as memories of wartime faded, the regional offices would all be closed down, the strolling minstrels and teaching players of CEMA days much to the annoyance of Ralph Vaughan Williams would be disbanded, and the best for the most soon turned into the best for the educated few. This was the era which many look back on as some kind of golden age.

Demand for the arts and great expectations of what they could offer would soon rise to the surface. This was due to a range of factors: publicly funded education post-1944; the local government act of 1948 which for the first time authorised spending on the arts; increasing social mobility; the growth of the mass media and especially television; changes in the definition of culture from the culcha of aristocratic connoisseurs to something more inclusive and all-embracing; the concept of equal opportunities, still a new idea to some; and the very gradual shift in the economy from heavy industries to the creative industries and financial services. Successive Arts Council annual reports responded to these tendencies in the 1950s by saying, We must provide oases of comfort in this Sahara of mechanised mediocrity. In other words, Stop the world I want to get off. Literature was allowed in as an artform eventually but that was about it. As someone said, the Arts Council was systematically filtering out from public subsidy most of the creative art in this country. The Arts Councils reply? In the 1950s again, the motto carved over the door of a patrician nursery in ancient times might be one for the Arts Council to adopt few, but roses. The assumption of a classical education and the idea of a patrician nursery were both very characteristic of the times.

The picture today

Now, after 61 years of the Arts Council and its work, lets revisit Keyness priorities and the chartered objectives and see where we are with them today. Consider his priority number two opening the doors to the arts. Well, weve moved on from we come bearing gifts to the few via we come bearing gifts to the many to we dont bear gifts at all we support the arts, the most for the most, with an emphasis now on audiences as well as on excellence. As Joan Littlewood once said, if you offer the public anything less than the best, youre just being patronising. The annual grant has risen from £235,000 to £415.5m (thats from £29m to £415.5m in todays money) plus some £140m from the National Lottery. Instead of a handful of regularly funded organisations, we now have more than 1,100 regularly funded organisations spread all over the country, not to mention those funded through our open application programmes. Support from the public for government investment in the arts is at an all-time high, with 79% of the population now agreeing that arts and culture should receive public funding. That really would have surprised the Bloomsbury set, with their oft-repeated views on the masses. Arts attendance is also at an all-time high 67% of the population attended at least one arts event in the last year thats 26.4 million adults and the same figure as for active sport. Add those who participated but did not attend and the figure goes up to 76%. Whichever way you slice it, Keyness priority has come true in ways he could only dream of.

As for priority number three the buildings since 1993, of course, the picture has improved beyond all recognition. Keynes said the Council would never be able to afford the proper housing of the arts. Well, he was wrong about this, but in a good way. Following the launch of the Lottery, for the first time ever a major programme of modernisation and refurbishment could take place across the country: new buildings designed, old ones renovated, new organisations developed and placed in new settings, equipment replaced. We had some lively discussions about where the boundaries of the arts should be drawn, including a fierce debate about Morris dancing and another one about conjuring (during which we discovered that a scary number of MPs had an interest in this). But on the whole we got it right, and the entire arts ecology changed in this country, for the better. So Keyness priority number three has happened again well beyond what he could even dream in 1945.

And so to Keyness first priority the independence of the artist and how to draw the line between accountability on the one hand and interference on the other. On the first part of this, the independence of the artist, I know of no attempt, ever, on the part of central government directly to interfere with the content of the arts or the behaviour of artists. This is unlike in the United States and on the continent of Europe, where this happens all the time: in the States largely because of corporate investment in the arts, and in Europe, largely because of the state monopoly of the arts. On the arms-length principle, where does overall policy (the role of government) end and implementation (the role of the Arts Council) begin? Well, the line was always going to be difficult to draw, but that doesnt mean it isnt worth drawing; and it does most certainly mean that the price of independence is eternal vigilance.

The Arts Council may not be perfect though I believe its a much more efficient organisation than its ever been in its history before but if it was disbanded or dismantled it would have to be reinvented in a very similar form. Jennie Lee, the first-ever minister for the arts in the mid-1960s, put this well. She was concerned that as the arts moved higher up the political agenda, which they inevitably would, there would be a growing temptation to politicise them. Having a minister for the arts should never, she said, be confused with political control. And she added, Political control is a shortcut to boring, stagnant art; there must be freedom to experiment, to make mistakes, to fail, to shock or there can be no new beginnings. It is hard for any government to accept this. Hard, but essential. That in the end is why we have an Arts Council.

Sir Christopher Frayling is Chair of Arts Council England.

w: http://www.artscouncil.org.uk.

This is the edited text of a talk given by him at Charleston House in May 2007. Charleston was where John Maynard Keynes, the originator of the Arts Council, once lived.