BME people in children’s publishing are often “pressured to comment on diversity issues” amid expectations their books will focus on cultural stereotypes.

Black and minority ethnic (BME) publishers face a complex set of unconscious biases that stop diverse children’s books from reaching libraries and bookstores, new research suggests.

The study, commissioned by Arts Council England, explores the experience of BME librarians, authors, illustrators, and children’s book publishers, finding it is marked by “racism and microaggressions” and harmful stereotypes about what books written by and for Black people in particular should look like.

More than half of 330 survey participants agreed the publishing process was more challenging for BME people due to the industry’s tendency to favour established authors and perceptions of a “limited market” for books featuring diverse characters.

BME respondents were more significantly more likely than their white colleagues to think that a lack of role models discouraged BME people from becoming writers and illustrators (60% versus 26%), that more needs to be done to address unconscious bias in the sector (76% versus 53%), and that BME writers are expected to appeal to a narrow audience (54% compared to 15%).

READ MORE:

* Diversity data reveals surprising trends

* Arts diversity: The quota conversation

* Arts and ethnicity: responding on race

One self-published author interviewed for the research commented: “The Black stories they [publishers] say people are interested in are about slavery, asylum seeking, extremes of culture like spiritualisation, dreadlocks. There’s nothing wrong with those things but they’re not my story.”

‘Imposter syndrome’

Interviewees explained how they felt unwelcome in the industry: BME publishers recounted instances including a publishing house that only wanted white characters on book jackets, a colleague who made “ignorant” comments about slavery being beneficial to Black people, and a media personality who tried to give them their coat at an event.

As a result, some BME workers experienced “near-constant feelings of imposter syndrome”.

They also felt resentful about often being pressured to promote or comment on diversity issues because of their race. The report notes this led to some authors “exploring alternative routes to publishing which afforded them greater creative freedom”.

One librarian/author felt they were the “go-to person” for diversity issues in the library sector: “That really doesn’t feel very diverse a lot of the time, if it’s always my voice that’s coming through.”

Additionally, survey respondents overwhelmingly felt that diverse books were expected to focus on issues faced by underrepresented groups (75%).

Discomfort around diversity

The report suggests that fear of being ignorant or making token gestures is hampering a genuine desire to improve diversity in publishing.

“Concerns around cultural sensitivities and ensuring authentic representation of diverse characters could lead to publishers being reluctant to take on submissions which include diverse characters.”

Interviewees noted there was encouragement, but insufficient support from publishers to include diverse characters in the books they created: “[they] were unsure where to go for guidance and had concerns about backlash and a ‘blame culture’ through blogs and social media if they made a mistake.”

The report recommends mandatory diversity and inclusion training for publishing sector workers, prioritising those in key decision-making roles.

Supply chain

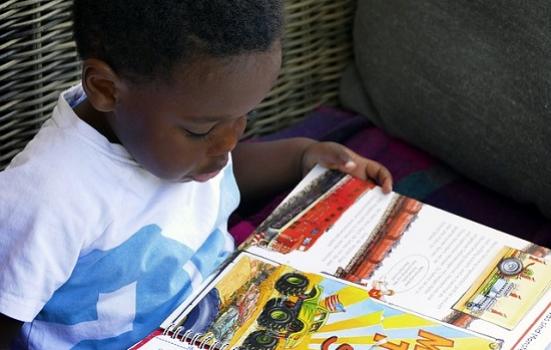

It is also suggested that a lack of communication means that diverse books, “even if they are available, are not reaching shelves and therefore children and families”.

Publishers and agents who receive a high volume of submissions are likely to rely on traditional acquisition methods and established clients, which can freeze out diverse authors and books featuring diverse characters.

The report also says the industry perceives there is a limited market for diverse books. One school librarian relayed an anecdote about the popularity of several books featuring Black girls:

“There was nothing in them that wouldn’t relate to other teenage girls, but the characters were Black. She [the author] had another idea for a story and I really wanted her to be able to bring that to be published … [I thought] ‘Let’s talk to some of the specific publishers and get them to commission something’,” they said.

“She had an idea and the response I got was ‘this just won’t be popular; it won’t have a wide enough popularity.’”

Guidance for teachers and librarians and funding to introduce more diverse books to school libraries was recommended in the report.

Comments

ViewFromTheBoundary replied on Permalink

Surely this is just an entirely predictable result ...