Can free editorial and reviews get your message across just as well as paid-for advertising? Teresa Crowley explains how to calculate AEV.

Infoeco (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons

Through sustained engagement with radio, television, online media and broadsheet publications, many arts organisations make valiant attempts to raise their public profile. An enhanced profile and a healthy upward trend in audience figures help when applying for grants or in soliciting philanthropic support.

Often with limited advertising budgets, cultural institutions rely on the art of the carefully crafted press release to catch the attention of a news desk. A positive review of a show or exhibition will swell the attendance numbers, and one that is less than favourable will at least generate some debate or galvanise supporters to attend (or so it is hoped).

How much a publication charges for advertising is a reflection of both its circulation and reputation

As well as reporting on visitor numbers and analysing comment cards for the positive and the negative, there is a trend towards using the advertising equivalency value (AEV) to communicate the value of media coverage.

AEV is a tool that has been used in PR for many years to assess the benefit to a client from media coverage for a PR campaign. It is calculated by measuring the column inches in print, or seconds in the broadcast media, and multiplying the figures by the medium’s advertising rate, generally charged by inch or by second.

The resulting number is what it would have cost at market rates to place an advertisement of a correspondingly large size. For an arts organisation with an effective press network but a limited advertising budget, it can be an impressive measure of its success in this area, particularly if it is communicated through an effective infographic, like the one below.

The formula in practice

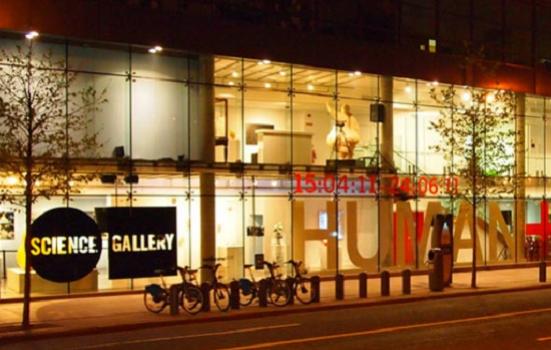

The Science Gallery at Trinity College Dublin is one such organisation that has deployed the AEV of press coverage. Unlike most science centres, it has no permanent collection but instead hosts a number of temporary exhibitions each year. Established in 2008, it has seen its visitor numbers jump from 242,000 in 2011 to nearly 410,000 in 2015.

The detailed infographics in its 2014 annual report demonstrate the value of press coverage, with the reported value growing from €1.87m in 2011 to €2.65m in 2014. The figure of 564 national print media articles is further broken down into the number of column inches by square centimetres. The broadcast minutes are displayed in ever increasing circles from 221 minutes in 2010 to 1,408 in 2014 (from a total of 150 broadcast features). The graph demonstrating the total PR value shows an impressive total for the year of €12.1m.

While capturing and decoding this data is a huge logistical undertaking, if credible, the AEV equates to a value that no museum could afford to ringfence for advertising, and helps to determine the cost̶ benefit analysis when pursuing a media campaign around an exhibition or event.

Advertising rates

How much a publication charges for advertising is a reflection of both its circulation and reputation. The Daily Mail has a circulation figure of 1,787,096 compared to the Financial Times’ figure of 198,237 (according to the Audit Bureau of Circulation via Wikipedia). Despite its lower circulation, the Financial Times can charge considerably more for advertising because it is perceived to be the more credible publication with a wealthier readership.

When using the advertising rates of various print and broadcast media, both factors are taken into account. The AEV allows PR agencies to compare their results with advertising, and now enterprising cultural institutions can avail themselves of this schematic to determine a useful value for their press coverage.

Editorial credibility

It should be noted that the PR value of these numbers differs from the AEV in that it includes a second multiplier which takes into account the idea that editorial is more credible and persuasive than advertising and should therefore carry more weight than AEV alone.

The credibility of using AEV has generated much debate within the PR industry, with the focus on both its reliability and validity. It is appealing because it appears able to put a monetary value on media coverage and, by extension, allows PR agencies to compare their results with advertising.

There are problems though with deploying this rather blunt instrument, including the inherent assumption that the size of an editorial has equal impact to the size of an advertisement. Then there’s the so-called ‘credibility crisis’ in journalism, as an increasing number of news features relate to celebrities and the entertainment industry rather than to current affairs.

Perhaps the most obvious problem with AEV is that there is no paradigm to take account of a negative review. Whether any such paradigm would prove or disprove the old adage that ‘there’s no such thing as bad publicity’ is another question.

Teresa Crowley is an art consultant and writer based in Dublin.

Tw @teresa_crowley