Sculpture is often placed in public spaces, but simply making art public is not enough. Helen Pheby looks at how one sculpture project generated massive public engagement.

Wot for?, Why Not? This graffitied message, sprayed on House, a temporary work of art by Rachel Whiteread, sited on a street in East London in 1993, could be seen to be representative of the prevailing attitudes toward art in public spaces. I resist the term public art because simply to put art in a public space is not to make art public in an inclusive sense. To reach audiences who do not usually make the necessary physical and conceptual journey to traditional exhibition spaces in part due to an inability to consider options outside current experience is laudable but runs the risk of being counter-productive.

Appreciation

The term public is rather misleading. Of course, the public consists of many individuals, all with differing types of appreciation for the visual arts and including those for whom art is of little relevance. The purpose of making art public cannot be a mass conversion, but should fulfil the right of all to encounter the arts and should offer contextual information that does not patronise.

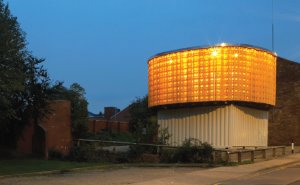

Placing art in a public space is often a difficult and time-consuming task. It requires co-operative working relationships between the artist, the organising body, the funder, the local council, and crucially, key residents in the city, town or village being given the work. Yorkshire Sculpture Park recently managed the installation of Cratehouse for Castleford by German artists Winter/Hörbelt, whose sculptures throughout the world are motivated by a wish to reclaim lost public spaces for the meeting, enjoyment and benefit of local residents and visitors.

Funded by Arts Council England, Yorkshire, the work was sited in the birthplace of Henry Moore, a West Yorkshire town currently the subject of culture-led regeneration initiative and the subject of a major Channel 4 documentary series. The town was chosen because of its significant, yet under-represented cultural heritage, and its comparative economic deprivation despite its geographical proximity to thriving Leeds.

Winter/Hörbelt presented their ideas to community representatives, who responded enthusiastically and the artists subsequently visited local schools and met with residents to discuss and adapt their proposal. Yorkshire Sculpture Park initiated a supporting programme of outreach events, including a free guided tour of an exhibition of sculpture by Henry Moore at Tate Liverpool, paid for by Arts Council England, Yorkshire.

When Cratehouse for Castleford opened in September 2006, the local press received more letters on the subject than they had on anything else in their history and the response was decidedly mixed. Among the responses were comments such as The Cratehouse is an affront to human sensibility, Its an eyesore, and not in a very good location tucked out of the way down here. I dont think it will get a lot of interest, and I thought maybe Cas folk are like those recovered beer crates, if only they would let the light shine through. Dont do yourselves down by complaining about art; support those doing a good job trying to make things better. The newspaper ran full page debates for several weeks and hosted an online poll that revealed, more or less allowing for the constantly changing nature of online polls, that 60% of the residents found it to be an eyesore, 30% thought it was beautiful and 10% didnt care. To understand the true power of art in public spaces one should concentrate on that 10%.

Opportunities

For a community that does not have access to an art gallery in their town or a museum displaying evidence of their rich cultural past, engaging 90% of the residents in a debate about what does or does not constitute a work of art and, crucially, what their town deserves culturally, presents a unique opportunity for discussion, education and, most importantly, dialogue between bodies whose remit it is to promote access to the arts. In the months since Cratehouse opened, residents have begun to organise educational and social activities in the space, including using it as Santas Grotto, and have actively campaigned for a planning permission extension to September 2007. It has simultaneously raised the profile of Castlefords regeneration to those best placed to support the town financially and politically.

This case suggests some possibilities for those considering placing art in spaces beyond the traditional and to an audience who have not chosen the experience. If the local community is respected, the work substantially mediated, and the project fully supported by all the bodies it represents, then there is a powerful and significant opportunity to engage with wider audiences and to explain wot for.

Helen Pheby is the Deputy Curator at Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

w: http://www.ysp.co.uk