There is an assumption that becoming a charity is a given for an arts organisation because everyone else is. However, this is not always essential and it is not necessarily desirable. Jackie Elliman outlines some of the benefits and disadvantages.

What is a charity? Until the Charities Bill currently going through Parliament becomes law the definition of a charity is over 400 years old. In 1601 the Statute of Elizabeth defined charity as the relief of aged, impotent and poor people, the marriage of poor maids, the advancement of education, the advancement of religion, the repair of bridges and other purposes beneficial to the community. Over the centuries other charitable purposes came into being because the courts decided that they were analogous to one of those original charitable purposes. In 1943 a court, decided that the Royal Choral Society was charitable, because a body& established for the purpose of raising the artistic taste of the country and established by an appropriate purpose which confines them to that purpose, is established for educational purposes.

So, an arts organisation that considers itself to be charitable must show that its work is of a standard to raise the artistic taste of the country if it is to be educational. Should it rely entirely on being educational it will be confined to that purpose, so most arts organisations applying for charitable status try to demonstrate other purposes beneficial to the community. If the new Bill becomes law, all charities will have to demonstrate public benefit. Arts organisations set up by individuals wishing to perform their own work or the work of a single writer can have problems obtaining charitable status. To the Charity Commission the private benefit to the individual or group outweighs the public benefit of the work, however much it raises the artistic taste of the country.

It can be done, though: ITC (the Independent Theatre Council) helps dozens of performing arts companies to become charities each year. ITC members tend to be committed to accessibility: many perform in places where the public may come across their work by chance as well as by intent, such as parks, shopping centres, streets. Most now include education work, outreach work and work that links in with local communities as standard in their portfolios. If you work in this way your work is likely to be seen as being of public benefit.

So why become a charity? There are the following tax benefits:

" Charities do not pay Corporation Tax on any surplus they may have at the end of a trading year.

" VAT is zero rated for charities on some supplies and on some outgoings (but not many).

" Charities have 80% relief on business rates and exemption from the full 100%,at the discretion of their Local Authorities.

" Only registered charities benefit from tax relief on giving from sponsors, Gift Aid, covenants and payroll giving.

Most importantly, if an arts organisations work is charitable in nature it is likely to be work that charitable trusts and foundations will support. These bodies are usually only able to give money to other charities. Sometimes they may be prepared to give money to an intermediary charity to pass on to a non-charity. If you are regularly presenting work that meets the criteria and approval of these funders, charitable status is likely to be appropriate.

Some of these benefits are not restricted to charities. Most arts organisations in receipt of public funds are structured as Companies Limited by Guarantee (CLGs), with a constitution very similar to that of a charity. Such companies are exempt from Corporation Tax and can benefit from up to 80% (discretionary) relief on business rates.

There are many administrative implications of becoming a charity:

Accounts: Charity accounts are more complex than standard Company accounts.

" They must distinguish between restricted funds that are for a specific purpose and other, unrestricted, funds.

" They must comply with the Charity Commissions Statement of Recommended Practice.

" The level at which it is compulsory to have an audit is lower than that for a non-charitable company.

Annual Return: Charities make an annual return to the Charity Commission as well as to Companies House and, annoyingly, these forms do not ask for identical information. The Charities Bill is proposing the introduction of a new organisation structure for charitable companies the Charitable Incorporated Organisation which will only have to submit one set of annual returns and accounts.

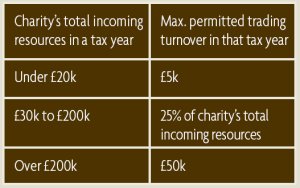

Trading: As already noted, one of the main points of charitable status is tax relief on any surplus income generated in the process of achieving the organisations charitable objects. Anything done for this purpose is primary trading. If a charity undertakes trading outside the parameters set out in its Memorandum & Articles this will be secondary trading and only a limited amount of tax relief will apply. For instance, if an arts organisation were to sell the script of a show after a performance this would be linked to the performance and to its charitable purpose of promoting art; profits made in this way would not usually be taxed. If, however, this organisation decided to open a bookshop this would probably be outside the original charitable purposes and the tax relief would be limited. At present it is as shown in the table below.

Trustees: Charitable status is not an organisation structure in itself. Most arts organisations register as Companies Limited by Guarantee and later apply for the company to have charitable status. In many companies, the Directors are the people who also run it on a day-to-day basis. Once a company becomes charitable, in most cases, paid staff cannot serve on the Board. The Directors of a charitable company are Trustees of charitable funds; they have to take more care than other company directors to avoid any conflicts of interest. If a charitable company really feels that, say, the Artistic Director should be a member of the Board they will have to make a special case to the Charity Commission.

The situation has been complicated by the recent ruling that if all the Trustees of an arts organisation are unpaid the organisation is run on an essentially voluntary basis and it will be exempt from VAT on ticket sales. Whilst some companies have benefited from reclaimed output tax and retention of VAT on sales, others have suffered from the drop in the proportion of output tax they can reclaim. This has made the issue of whether a charity pays its board members important for the wrong reasons.

Jackie Elliman is Legal and Industrial Relations Manager for the Independent Theatre Council

e: j.elliman@itc-arts.org