The distribution of Lottery funding for the arts is a closed system, operating for the benefit of a small number of arts organisations but to the detriment of wider society and the economy, according to a new report by the authors who recently revealed England’s regional arts funding imbalance.

Tim Rawle (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Nearly 80% of Arts Council England’s (ACE) Lottery funding has gone to less than 20% of local authority areas since the National Lottery was launched, according to a new report by the authors of the RoCC report, which revealed the extent of England’s regional arts funding disparity.

The PLACE report – on Policy for the Lottery, the Arts and Community in England – states that directions and guidance issued to ACE by the Secretary of State in relation to community-based and participative work “appear at best to have been given no priority, at worst to have been substantially and systematically ignored”.

It concludes that “gross imbalances” in the distribution of arts Lottery funding are hindering efforts to realise the “wider potential that the arts and culture have within society and the economy”, as well as compounding geographic inequalities in grant-in-aid arts funding across England.

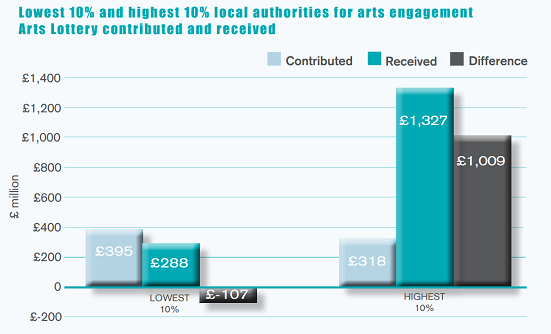

Comparisons showing the amounts that different areas of England contribute to arts Lottery funds through ticket purchases throw the situation into sharp relief. Of the 10% of local authority areas where engagement with the arts is, according to DCMS figures, at its highest, three-quarters are in the “extended cultural catchment” of London.

Lottery funding to these areas has totalled more than £1.3bn since the launch of the National Lottery in 1995 – an estimated £1bn more than has been generated for the arts Lottery fund through ticket sales in these areas. Arts Lottery funding to five London organisations alone – the Royal Opera House, the Royal National Theatre, English National Opera, Sadler’s Wells and the South Bank Centre – has amounted to £315m.

By contrast, the 10% of local authorities where arts engagement is lowest have received a total of just £288m during the same period – an estimated £107m less than the arts Lottery revenues generated from ticket sales in those areas. The local authority area with the poorest net return to Lottery players is County Durham, where an estimated £34m has been contributed to the arts by Lottery players since 1995, during which time the area has received only £12m for arts activity. The area with the highest net return is the City of Westminster, whose population has contributed an estimated £14.5m while its arts organisations have received £408m.

PLACE report, page 31

Pointing out that “Lottery funds have been, and are increasingly being, used to fund the same organisations for the same programmes of work that were previously funded only through grant-in-aid”, the PLACE report accuses ACE of operating a “closed system” that works “to the very considerable benefit of a small number of arts organisations, but to the substantial disadvantage of the wider potential that the arts and culture have within society and the economy”.

David Anderson, Director General of Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, who used his first speech as President of the Museums Association to attack the centralised funding system through which “wealth attracts wealth [and] poverty begets poverty”, commented: “Public funding is supposed to counter market failure. Instead, as the PLACE report reveals, the impact of arts Lottery funding in England is only to deepen national inequity. It is strategic policy failure on an heroic scale. The arts funding system in England is broken. The time to change it is now.”

But ACE denies that it has failed in this respect. In a statement, Chair Sir Peter Bazalgette said: “We face a real challenge in making sure National Lottery money gets used in areas where there is not enough great art and culture, so we welcome the debate that this report provokes. Twenty years ago the principles underpinning how to invest National Lottery income were described by John Major quite simply as ensuring more people were given access to the best of the arts and culture. Let us make it clear; we stick very closely to those principles. We also closely follow the DCMS’s Lottery directions and the joint policy on how Lottery should be spent as agreed by all the Good Cause distributors.”

The authors argue that the privileged groups who are regular attenders at England’s most generously funded cultural organisations are already deriving the greatest benefit from grant funds provided by taxpayers, but are also benefiting disproportionately from revenues generated for ‘good causes’ by Lottery players across the country.

This is contrary to ACE’s stated intention in 2010, when it made the case to the DCMS for the reinstatement of a 20% share of good causes money for the arts by pledging to fund projects in areas of the country that lacked established arts and culture infrastructure, and to support “parts of the infrastructure we wouldn’t otherwise be able to.”

Co-author of the report, David Powell, told AP: “The direction from Government on the priorities the arts Lottery is to address are clear. The facts show they are not being followed. But, whether there are directions in place or not, there is just something ethically wrong with a system that has delivered £1.327bn of funding to the 33 local authority areas in the country where people are already most engaged with the arts and only £288m to the 33 areas where people are least engaged, where more people live and where more households spend more on the Lottery. When five very large and already well-funded arts organisations in the capital have also received more from the arts Lottery than those 33 least engaged areas since 1995, that is a call for action.”

Questions are raised in the report about the extent to which ACE is collaborating with local authorities to ensure that the intended benefits of arts Lottery funds are felt across the country. Citing “the fundamental duty of public funding to work towards equity in access to public services”, and ACE’s commitment to making the arts “an integral part of everyday public life, accessible to all”, the report states “…it might be expected that Arts Council England would have placed at least the same importance on its partnership with local government to secure that access to opportunities for participation, enjoyment and skills development as it does on its work to secure international excellence in production in the nation’s arts.”

Comparisons are made with the decentralised regional structure of the Heritage Lottery Fund, which aims to “ensure that local sensitivity and responsiveness is as present in its decision-making processes as are specialist national considerations” and provides professional development resources to help prioritised local authority areas support new applications and new applicants. Missing “policy, programmes, funding and implementation and a conspicuous absence of the DCMS” are blamed for enabling arts Lottery funds to be diverted from their intended beneficiaries: “If research clearly indicates the beneficial impacts of the arts and culture on our education system, our economy or on our health, why is it that Arts Council England does not already have major programmes to develop and support precisely those benefits at community level through arts Lottery funds in the same way that its sister Lottery distributor bodies do?”

Among the recommendations for a redistribution of Lottery funds is a proposal for a three-fold system which would see 40% of Lottery funds allocated for developing the arts at local level to promote individual and community wellbeing; a further 40% for wider economic regeneration at regional level to promote creative cultural production; and the final 20% available to individual artists and arts-led projects to encourage new talent, innovation and excellence in work locally, regionally, nationally and internationally.

In response to the recommendations, dramatist Lee Hall, who was a vocal campaigner in response to arts budget cuts by Newcastle City Council, said: “…this report is an urgent intervention to secure the vital provision of art in the very places where the most money is raised… It is vital that we maintain and foster access to everyone no matter what class you are or where you happen to live. The extraordinary achievements we have made as a nation are very much under threat but the good news is this report outlines a clear, achievable way the Lottery can transform the landscape and secure a brilliant future.”

Comments

sencilla replied on Permalink

ACE Funding